laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

Arpentage

Arpentage is a project by the collectif Facteur and least aimed at amplifying the voices of residents and preserving the cultural and environmental heritage of the villages of Binn and Bourg-Saint-Pierre in the Valais. Geographically distant from each other, these villages face similar problems. Both located on main roads that once linked Switzerland and Italy, they have suffered from the opening of cross-border tunnels that have speeded up travel. Once bustling, lively stopping-off points, they are now being abandoned in favour of faster routes, and are becoming remote places where jobs are scarce, forcing their inhabitants into leave. This creates a loss of collective memory and transmission of local knowledge, as well as the loss of traditional know-how: rich resources that are disappearing and are strongly linked to the preservation of biodiversity and ecological heritage.

The physical and anthropological geography of these two territories gives rise to reflections on the relationship between isolation and communication, the nature of border areas, the relationship between mountains and plains, hospitality, migration, the idealisation of landscape and tourism, and the consequences of anthropisation and the resulting depopulation of the Alps.

Through the sharing of knowledge and know-how, the artistic process and the involvement of citizens, Arpentage will put into practice the major principles of participation: listening to and identifying the needs and demands emanating from the community we meet.

A series of nomadic residencies will enable the artists to investigate the area and reflect on the avenues to be developed in the project d’un champ à l’autre, including a co-creative contribution to the exhibition at the Binn Regional Museum and the design of a contact mechanism between the two communities of Binn and Bourg-Saint-Pierre.

A participating community

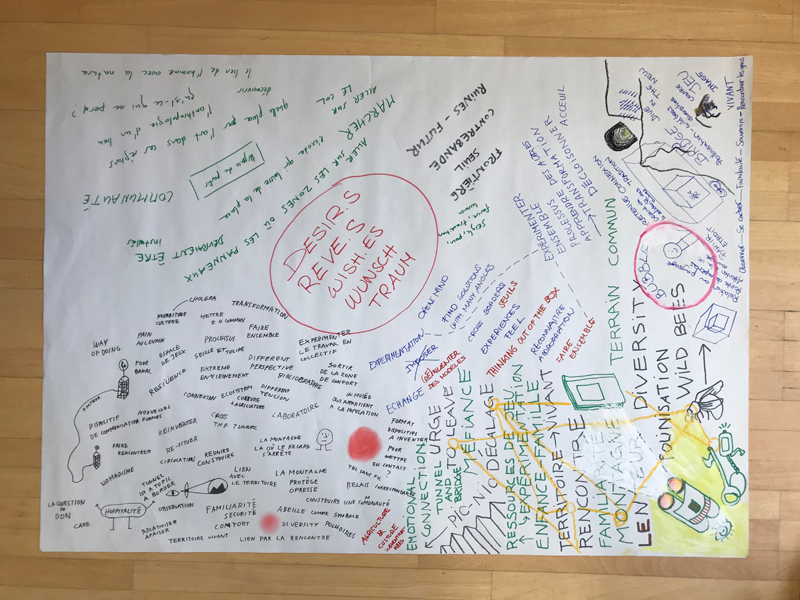

In 2023, least and the Facteur collective met with residents, academics, activists, and institutional representatives to address the area’s myths, histories, and issues. The different skills of the people we met, both in Binn and in the Entremont region, brought to light complementary and cross-disciplinary aspects that enhanced the research project. Together, the team imagined new experimental frameworks for cultural outreach and discussed the issue of transforming our practices and our professions in order to develop new horizons that take into account the environment, society, and culture.

Situated research

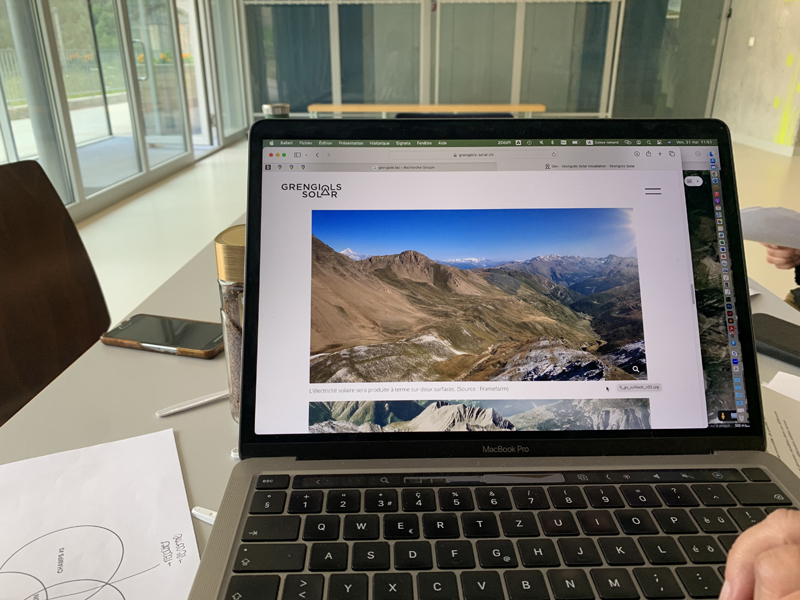

A number of avenues were explored during the research phase. On a cultural level, the promotion of heritage and traditional practices, such as the processions marking the rhythm of the seasons or the promotion of a collection from the Binn museum, were the central points of the discussions. From a societal point of view, the research highlighted the trauma linked to depopulation and the weakening of the social fabric, the conflicts linked to pasture management, and the tensions between tourism and the local community. Finally, on the environmental front, the installation of photovoltaic panels on mountain pastures, crop rotation, and the protection of endangered endemic species, such as the Grengiols tulip, are some of the major issues that emerged.

From research to project

The encounters and explorations that took place during the Arpentage project opened up a series of conceptual avenues for the realisation of d’un champ à l’autre / from one field to the next, a co-creative, experimental, and nomadic artistic and curatorial project that will take place in 2025 and 2026. There were no pre-established ideas at the outset of the project: on the contrary, it was through conversations and meetings during the research process that the metaphor of the “field” in its various guises emerged as the central element of our reflection. d’un champ à l’autre is therefore the embodiment of the questions and perspectives that emerged during Arpentage.

newsletter

Stay up to date about our latest activities, articles, inspirations and much more!

artistic team

Rémy Bender – artist collectif Facteur

Basile Richon – artist collectif Facteur

Gabrielle Rossier – architecte collectif Facteur

Christel Voeffray – artist collectif Facteur

least would like to thank all the people who contributed to the project by sharing their time, knowledge, and resources:

Andreas Weissen (former Secretary General WWF Upper Valais, Binn and Brig); Gabriel Bender (sociologist, director of the Malévoz cultural residence); Maria Anna Bertolino (anthropologist – scientific collaborator CREPA – Centre régional d’études des populations alpines, Sembrancher); Luzia Carlen (art historian, museologist, curator of the Binn Regional Museum and cultural outreach officer, TWINGI, Binn Valley Nature Park); Jean-Charles Fellay (General Secretary CREPA – Centre régional d’études des populations alpines, Sembrancher); Stéphane Genoud (energy engineer, HES-SO Valais-Wallis, Sierre); Roxanne Giroud (cultural mediator); Fanny Glassey (socio-cultural facilitator, ASDE); Sabrina Gurten (environmentalist and activist, Grengiols); Mélanie Hugon-Duc (anthropologist and director of Musée de Bagnes); François Lamon (Canon of the Great Saint Bernard, Martigny and Bourg-Saint-Pierre); Beat Tenisch (former president of the municipality of Binn, retired teacher, Binn); Hélène, Suzanne and Bernard (retired farmers, Fully).

media

Living Soil

Reading

Although we walk on it every day, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

Fences and Power

Reading

The fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

Arpentage

Faire commun

d'un champ à l'autre / von Feld zu Feld

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Autumn in the Garden

Reading

“We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn”.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

How happy is the little stone

Reading

Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life.

Peau Pierre

Arpentage

Faire commun

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Reading

Yves Citton discusses commons, negative commons, and sub-commons with us.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Experiencing the Landscape

Reading

The complexity of the term ‘landscape’ can best be understood through the concept of ‘experience’.

Vivre le Rhône

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Heidi 2.0

Reading

The Alps and “proximity exoticism.”

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Putting Off the Catastrophe

Reading

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously?

Common Dreams

Vivre le Rhône

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Living Soil

Although we walk on it every day and it is essential to our food security, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives. What crucial roles does soil play in maintaining the balance of ecosystems? How can we protect it? And how can artistic practices help?

Below is an interview with Karine Gondret, a trained soil scientist and geomatician, HES-SO research associate and lecturer at the Geneva School of Landscape, Engineering and Architecture (HEPIA). Her research focuses on soil quality assessment and mapping.

What is pedology?

A branch of soil science, pedology focuses on the study of soils, i.e. the interactions between living organisms, minerals, water, and air that take place beneath our feet. In pedology, we examine everything that lies between the surface and the first, purely mineral layer, i.e. around 1.50 m deep in our latitudes. Beyond that, when only minerals remain, we enter the field of geology. The role of the pedologist is also to map the soil.

What is meant by good quality soil?

Broadly speaking, good quality soil is soil that is capable of performing the functions necessary for the survival of all living organisms and their environment. Several functions are very important, beyond the most obvious, that of food or biomass production. Soil infiltrates, purifies, and stores water, and recycles nutrients and organic matter. There is also the genetic reserve function, which is still seldom studied. Penicillin, for example, was discovered in the soil. So it’s crucial to protect our soils.

What parameters need to be taken into account to assess the quality of a soil according to its functions?

In general, the higher the organic content of soil, the better it is able to perform its functions. By organic, we mean all living things (earthworms, micro-organisms, bacteria, etc.) and all carbon-rich compounds derived from living things (corpses, excrement, roots, dead leaves, compost, root and bacterial exudates, etc.). Functioning soil is living soil, and much more!

There are several other essential parameters, such as soil depth, pH, texture, porosity, etc. Depending on the function, certain parameters will be more or less important. For example, the function of supporting human infrastructure (roads, buildings, etc.) will inevitably be detrimental to the biomass production function. That’s why politicians have to make choices about the functions they want to protect.

Why is the presence of organic matter in soils important?

Organic matter is the basic food source for the soil’s fauna and micro-organisms. It is continually broken down by soil life into nutrients that are accessible to plants via soil water. Organic matter also improves soil porosity. Porosity is essential for the proper development of life, as it allows nutrient-rich water, air, and roots to circulate. Without this porosity, exchanges are much less effective, and as a result, its functions are much less effective.

In addition, organic matter is capable of increasing the soil’s capacity to store water and of mitigating flooding in towns downstream. It can also retain nutrients and pollutants through its electrical properties. Finally, organic matter that is stabilised in the soil contains around 60% of carbon, and the more it increases in the soil, the more we limit global warming, because all the carbon that is not stored in the soil goes into the atmosphere in the form of CO2.

We’ve talked about what good soil is for humans, but what about the “more than human” world?

As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), soil performs functions that are essential to humankind. In truth, these functions are essential to the proper functioning of ecosystems, and humans simply benefit from them. For example, many pollinators spend part of their life cycle in the soil. These pollinators make it possible to obtain fruit and feed wildlife, which is beneficial for natural environments. But this fruit also benefits humans within agricultural and economic infrastructures, when it is sold. Humans and the environment are deeply interconnected, although we tend to forget this. Finally, compared to about fifty years ago, the organic matter content in most agricultural soils has halved. This means that these soils are becoming increasingly less effective at performing the functions they provide for us.

Images: Thierry Boutonnier, Comm’un sol, 2024. Photo: ©Eva Habasque.

As part of the Faire Commun research project, artist Thierry Boutonnier devised a method for sensitively assessing the quality of the soil in Parc Rigot. He organised a picnic on a long organic cotton tablecloth, which was then cut into pieces and buried in different areas of the park. After a few months, the tablecloth was dug up, and the amount of fabric consumed thanks to the soil’s bioactivity provided concrete information about its characteristics. What did you observe?

We haven’t yet finished carrying out the analyses in Parc Rigot, but we’ve observed the soil’s capacity to degrade organic matter through this experiment. In the soil, micro-organisms release enzymes that degrade organic matter (here the cotton tablecloth). We also observed that these micro-organisms were not all equally active: in some areas of the park, the organic matter was broken down very efficiently, while in other areas, the process was much slower. This means that in these areas, there are fewer nutrients available for the plants that grow.

People often don’t realise that there is diversity of soils, even in small areas. In the city, as in Parc Rigot, this diversity is even more marked because humans have had such a strong impact on the soil. There have been many interventions – areas have been completely renatured, others stripped, or artificially added – and this has led to a juxtaposition of very different soils. The challenge is to identify the areas that really work, and protect them.

Is it possible to improve soil quality?

When soil doesn’t have the necessary quality for a given function, we can intervene to improve it, for example by adding organic matter or by decompacting it (in compliance with the OSol ordinance in Switzerland). Nevertheless, soil quality only improves very slowly; sometimes it takes several human generations, sometimes improvement is impossible. Soil is a non-renewable resource, as it takes a very long time to create: it is said to increase by an average of 0.05 millimetres per year. In very steep areas, it even becomes thinner and thinner.

It can also deteriorate rapidly. It looks solid and is thought to be immutable, but nothing could be further from the truth. Even when we’re trying to improve its quality, we have to be very careful, because every intervention on the soil leads to its deterioration. It’s a delicate process that doesn’t always work – we’re still experimenting.

Soil is at the intersection of physics, biology, and chemistry. It’s a complex world, and by no means do we know everything about it. So it’s all the more important to protect it, because it’s where all plant nutrients are found, and as they develop, they form the basis of the diet of all mammals. The soil is truly the place where life is created.

Fences and Power

“We pray your grace that no lord of no manor shall common upon the common.

We pray that all freeholders and copyholders may take the profits of all commons, and there to common, and the lords not to common nor take profits of the same.

We pray that Rivers may be free and common to all men for fishing and passage.

We pray that it be not lawful to the lords of any manor to purchase lands freely, (i.e. that are freehold), and to let them out again by copy or court roll to their great advancement, and to the undoing of your poor subjects.”

The date is 6 July 1549. The peasants of Wymondham, a small town in Norfolk, England, have risen in rebellion. They are marching across the fields to cut down the hedges and fences of private farms and pastures, including the estate of Robert Kett, who surprisingly joins the protests, giving his name to the rebellion. As they march, they are joined by farm workers and craftspeople from many other towns and villages. On 12 July, 16,000 insurgents camp at Mousehold Heath, near Norwich, and draw up a list of demands addressed to the King, including those mentioned above. They will hold out until the end of August, when more than 3,500 insurgents will be massacred and their leaders tortured and beheaded. But what provoked this insurrection? And why was the repression so bloody?

Kett’s Rebellion was a reaction to the hardships inflicted by the extensive enclosures of common lands. These lands, which were of great economic and social importance, were managed according to rules and boundaries established by the communities themselves, guaranteeing a balance between their members. The plots were used for grazing, gathering wood and wild plants, haymaking, fishing, or simple passage, and even included shared farmland, where peasants each cultivated small portions of the collective land. The common land system thus contributed to the subsistence of the communities and, in particular, the most disadvantaged.

With enclosures, common land was reorganised to create large, unified fields, demarcated by hedges, walls, or enclosures, and reserved for the exclusive use of large landowners or their tenants. This gradual process of land appropriation was not exclusive to England but was a large-scale phenomenon that spread in various forms throughout Europe (and even more violently in its colonies) from the 15th century onwards. This is the phenomenon that Karl Marx describes in Das Capital as “primitive accumulation”: agricultural workers, deprived of their means of production (land), are forced to work for wages, possessing nothing other than their labour power. This was one of the factors that led to the emergence of capitalism, a process involving violence, expropriation, and the breaking of traditional social ties.

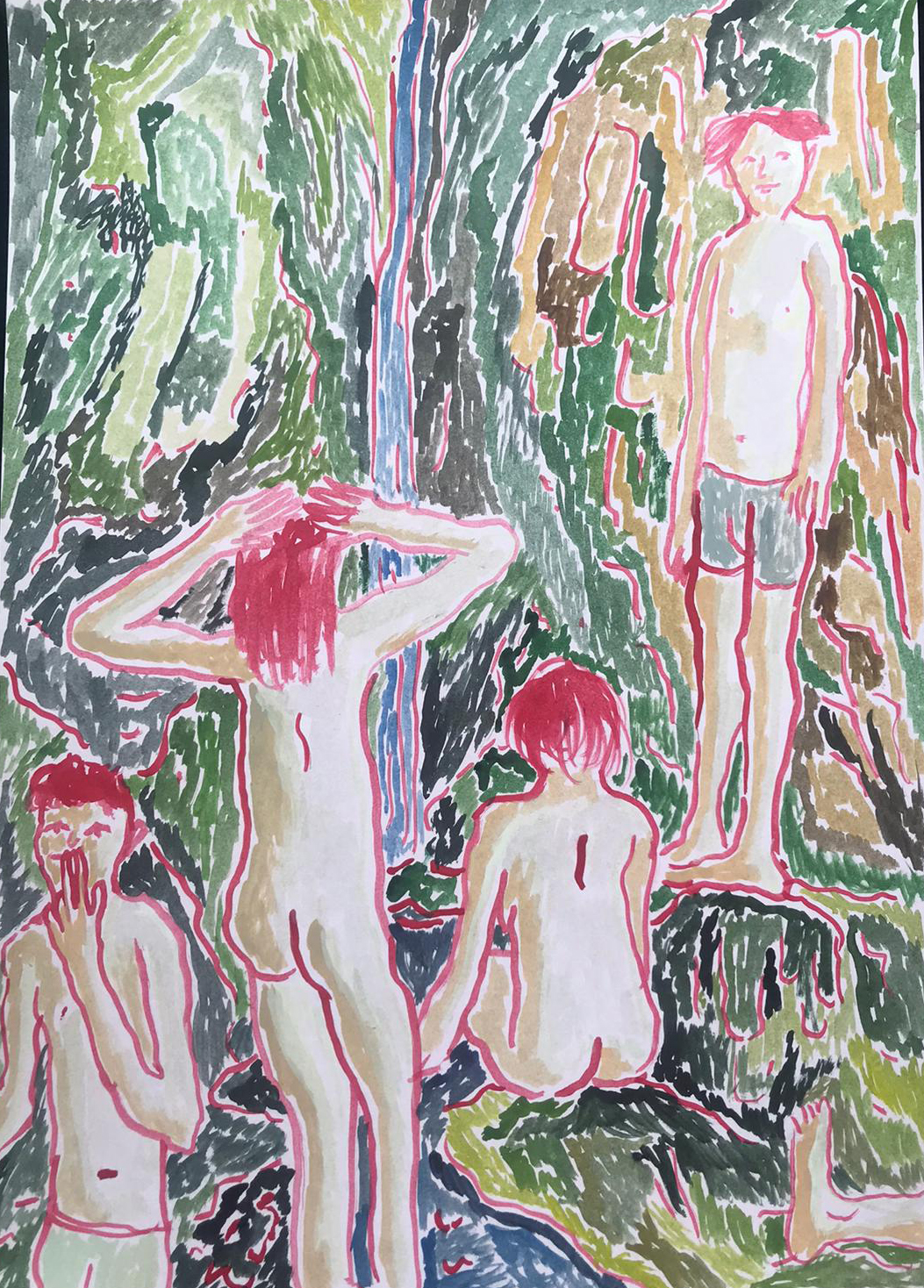

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

Another significant aspect of enclosures is their impact on the role of women. Until the Middle Ages, a subsistence economy prevailed in Europe, in which productive work (such as tilling the fields) and reproductive work (such as caring for the family) had equal value. With the transition to a market economy, only work that produced goods was considered worthy of remuneration, while the reproduction of labour power was deemed to have no economic value. What’s more, as we have shown, the loss of use rights over common land particularly affected already-discriminated groups such as women, who found in this land not only a means of subsistence, but also a space for relationships, knowledge sharing, and collective practices.

Feminist researcher Silvia Federici, in her celebrated book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, reflects on the link between the privatisation of land and the worsening of women’s condition: “For in pre-capitalist Europe, women’s subordination to men had been tempered by the fact that they had access to the commons and other communal assets (…). But in the new organisation of work every woman (…) became a communal good, for once women’s activities were defined as non-work, women’s labour began to appear as a natural resource, available to all, no less than the air we breathe or the water we drink (…). According to this new social-sexual contract, proletarian women became for male workers the substitute for the land lost to the enclosures, their most basic means of reproduction, and a communal good anyone could appropriate and use at will.”

The consequences of this exacerbation of power relations between the sexes were manifold: women found themselves increasingly confined to the domestic sphere, economically and socially dependent on male authority, and controlled in the management of their bodies by demographic policies that were essential to a society dependent on the flow of labour power. Control of the female body, through the condemnation of contraception and the traditional knowledge associated with care, became central to the emerging capitalist society. The witch-hunts that struck down thousands of women in Europe and America were part of this repression and control.

In the European colonies, similar processes of expropriation and violence were justified by the rhetoric of domination over “savages”. This pattern, based on the extraction of resources and cheap labour, continues to this day: think of the appropriation of indigenous lands in the global South for the exploitation of natural resources. Capitalism and oppression are two sides of the same coin.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality, wrote: “The first person who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of society. From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows, ‘Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’”

Rousseau’s thinking in this book is not without its problems, and, among other things, fuelled the dangerous myth of the “good savage”, which would in part justify colonialism. Yet these words represent a warning and a hope, inviting us to question the very foundations of society: structures, institutions, and economic systems are not immutable. Change is always possible, provided we have the courage to imagine it.

Autumn in the Garden

The gardener, hands immersed in the soil and in constant contact with plants, might seem to have an idyllic job in the face of urban hassles. But, according to Karel Čapek, nothing could be further from the truth. In his book The Gardener’s Year (1929), Čapek describes the gardener’s problems and tribulations in the face of frost, drought, and the overweening ambitions of small urban gardens. His wonderfully written tale, imbued with irony, offers a reflection on the complexity of human nature, not without a touch of humour and levity. Below is a short extract from the book.

We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn. While we only look at nature it is fairly true to say that autumn is the end of the year; but still more true it is that autumn is the beginning of the year. It is a popular opinion that in autumn leaves fall off, and I really cannot deny it; I assert only that in a certain deeper sense autumn is the time when in fact the leaves bud. Leaves wither because winter begins; but they also wither because spring is already beginning, because new buds are being made, as tiny as percussion caps out of which the spring will crack. It is an optical illusion that trees and bushes are naked in autumn; they are, in fact, sprinkled over with everything that will unpack and unroll in spring. It is only an optical illusion that my flowers die in autumn-; for in reality they are born. We say that nature rests, yet she is working like mad. She has only shut up shop and pulled the shutters down; but behind them she is unpacking new goods, and the shelves are becoming so full that they bend under the load. This is the real spring; what is not done now will not be done in April. The future is not in front of us, for it is here already in the shape of a germ; already it is with us; and what is not with us will not be even in the future. We don’t see germs because they are under the earth; we don’t know the future because it is within us. Sometimes we seem to smell of decay, encumbered by the faded remains of the past; but if only we could see how many fat and white shoots are pushing forward in the old tilled soil, which is called the present day; how many seeds germinate in secret; how many old plants draw themselves together and concentrate into a living bud, which one day will burst into flowering life—if we could only see that secret swarming of the future within us, we should say that our melancholy and distrust is silly and absurd, and that the best thing of all is to be a living man—that is, a man who grows.

Image: Natália Trejbalová, Few Thoughts on Floating Spores (detail), 2023.

Courtesy of the artist and Šopa Gallery, Košice. Photo: Tibor Czitó.

How happy is the little stone

In this brief poetic composition, Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life, represented by a small stone wandering freely. Far from human worries and ambitions, the stone finds contentment in its elemental existence. Written in the 19th century, the poem reflects the growing disillusionment with industrialisation and urbanisation, which led many to aspire to a more modest and meaningful life.

How happy is the little stone

That rambles in the road alone,

And doesn’t care about careers,

And exigencies never fears;

Whose coat of elemental brown

A passing universe put on;

And independent as the sun,

Associates or glows alone,

Fulfilling absolute decree

In casual simplicity

Image: Altalena.

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Swiss philosopher Yves Citton’s areas of research range from literature to media theory and political philosophy. We met him as part of our Faire Commun project to discuss a central theme of our research: the commons. Below is a transcript of part of his talk.

I’d like to introduce the “commons” by trying to qualify a certain image – which isn’t wrong, but quite partial – of the commons as pre-existing human appropriation. According to folklore, the Earth and its goods were shared by all animals and all featherless bipeds like ourselves. Then, according to Rousseau’s second discourse, human appropriation became the source of all evils.

This means that the commons are given as they are by nature. It’s true that the air we breathe, for example, wasn’t created by humans so that they wouldn’t die of asphyxiation: on Earth there is air, and we humans benefit from it. It’s a certain layer of the commons that we enjoy naturally, even if we don’t know exactly what nature means.

We can also say that air and water are quite similar commons. On Earth, there’s salt and fresh water, which is drinkable. But if you think about the reality of water today, the water we drink is more or less natural water. We know that it can contain chlorine, that it flows through pipes. Hence, to my mind, water isn’t at all a natural commons. It’s the result of an infrastructure, which can be public, private, or associative; it can be democratic or subject to capitalism. It’s mediated by the community or public institutions. In order to distinguish between public and private commons, I’d call this case public – a government has intervened, made regulations, and financed the pipes.

It’s still a commons, but one that has been constructed by humans, legislation, and political processes. Most of the time, when we talk about the commons today, these elements are inevitably involved. Even forests no longer look like they did before humans brought domesticated species and technologies into them. So I think it’s more realistic to say that the commons include a human artificialisation and preservation dimension. We don’t necessarily need to take care of the air – it’s enough not to pollute it – but we do need to preserve water, pipes, and infrastructures.

It’s interesting to consider another, slightly different model of the commons, i.e. language. Language didn’t precede humans, there was no French language 300,000 years ago; it isn’t an institution, nor an infrastructure regulated by a state that cares for and maintains it. French resides both within and between us. To my mind, it’s the most bizarre and extraordinary model of the commons, existing only because we own it: if all the people who speak French disappeared, there’d be no more French. (That’s without taking into account books written in French, which would remain of course). Knowing where a commons lies, whether it’s artificial or public, is no easy task. For me, what language highlights about the commons is the fact that it can exist without official regulation. The Académie française did not create the French language. Language is reproduced through culture and through children talking to their parents. It’s a commons: it’s neither totally public nor totally private.

Image: Mattia Pajè, Il mondo ha superato se stesso (again), 2020

The French language, air and water are elements that are necessary to our survival, and we’re grateful that they’re available to us: we can define them as positive commons. Conversely, there are negative commons, which are a continuation and a reversal of the latter. Researchers Alexandre Monnin, Diego Landivar, and Emmanuel Bonnet use the term “negative commons” to refer to nuclear waste, to cite only the most telling example. Whether a nuclear power station has public or private status doesn’t change the fact that the resulting waste becomes a collective problem for hundreds of thousands of years to come. It’s clear that nuclear waste is a commons, just as plastic and the climate are. Indeed, the climate, like water, is becoming an element that needs to be maintained if it’s to remain liveable. Some negative commons are therefore blending in with commons that were traditionally seen as positive. These negative commons pose a major problem: they feed our lives (the nuclear power station feeds my computer, which allows me to communicate) but they harm our living environments. Feeding and harming are seen as two sides of the same coin, at the same time. Nuclear energy provides me with electricity but harms future generations through the production of radioactivity.

If we develop this idea further, we can see finance as a good example of a negative commons: finance feeds our investments and the state budget but pollutes our environments by pushing to maximise profits at the expense of environmental considerations. How do we get out of this? How can we dismantle finance? It’s even more interesting to ask whether universities are not a negative commons: knowledge is developed, and research carried out, but the way universities operate can be toxic, with some teachers taking advantage of their power over their students, for example. There’s also bureaucracy that prevents us from doing good work at the same time as framing and structuring that work. There are toxic elements that need to be dismantled, but it’s not easy because they feed us. The intellectual exercise of projecting a negative commons hypothesis onto different subjects is therefore quite revealing.

There’s also the concept of undercommons, a term defined by Afro-American poet and philosopher Fred Moten and activist and researcher Stefano Harney. This term is based on the political ideas of the Black Radical Tradition in the United States. The over-representation of black people, particularly black men, in prisons in the United States today is dramatic, and there’s a continuity between slavery a few centuries ago and racial domination in this country today. The people who emerged from the slave holds were never considered as individuals in their own right. They therefore had to develop other modes of sociality, alternatives to the individualistic socialisation of the homo economicus, the small businessman, the white bourgeois. The communities that were threatened with lynching until a few decades ago and are now victims of police violence, live in conditions of marginalisation or at least do not enjoy the privileges that you and I, as white people in Switzerland or France, have been able to enjoy. These people have therefore developed an alternative, underground form of socialisation: a somewhat paralegal or semi-legal form of solidarity, since US law is made by white people for white people. Instead of seeing this form of solidarity as illegal, it might be seen as a different form of solidarity, outside the law, but one that is worthy of consideration and study. It enables ways of living that feed the commons, even if they’re less visible. And it could prove crucial for all of us: the infrastructures that sustain our luxuries and our forms of economic and social individualisation, as we know them today, may not last indefinitely. It would therefore be in our interests to familiarise ourselves with this form of “survival solidarity”. And of course, before doing so, it’s important to denounce and fight against the persistent oppression that weighs on marginalised populations.

I had the opportunity to work with Dominique Quessada, who came up with the idea of writing the term “commun” (commons in French) as “comme-un” (literally “as one”): his idea being that the commons belongs to everyone and to no one at the same time. The very fact of talking about the commons perhaps presupposes that the term is established, that there are people who see it as a real possibility, and that behind the dissolution of identity and property, the commons is something in which everyone can participate: it’s a plural, it’s neither mine nor yours. Above all, to write it “comme-un” suggests that the unity (of a certain people, of a community) that is often thought of as inherent to the commons is perhaps no more than “acting-as-if we were one”. Faced with the commons, we act “as one”, but we remain diverse, different, and sometimes antagonistic to one another.

Behind the commons there are always two concepts. First of all, there is the principle of unity: who are those who speak of a “commons”? On what do they base themselves? In reality, they can only defend a commons because they’re already united. Secondly, the commons is always a collective fiction: calling something a “commons” means that it is considered as such and thus develops characteristics of a commons. A public park is a public park because it is declared to be one. Thanks to this label, it’s possible to do things in this park that would otherwise have been impossible. But this remains a temporary fiction: a change of regime, a sale, an occupation of the site can always happen. In short, writing “comme-un”, or “as-one”, with a hyphen means asking two questions. Firstly, what is this unity, however heterogeneous, that allows us to say that there is a commons? Secondly, what is the fictional element, the dynamic that allows us to forge a concept that doesn’t exist? The imaginary dimension of the commons always remains central to its defence.

Experiencing the Landscape

In everyday language, the term “landscape” encompasses a variety of notions: it can refer to an ecosystem, a beautiful view, or even an economic resource. However, the complexity of the term can be better understood and approached through the concept of “experience”.

Experience is something that brings us into contact with the outside, with otherness: in this context, the landscape is no longer seen as an object, but rather as a relationship between human society and the environment. An experience is also something that touches us emotionally, that moves and transforms us. Viewing a “landscape” as such helps us realise how much it gives meaning to our individual and collective lives, to the extent that its transformation or disappearance leads to the destruction of sensitive markers of existence in the lives of its inhabitants. Experience can also be seen as a form of practical knowledge or wisdom. It is the kind of knowledge that is acquired by living in a place, which makes the people who inhabit a landscape its experts. Finally, experience is also a form of experimentation: this is the active aspect of our relationship with the world, enabling us to discover and create new knowledge and to bring to life what is yet only potential.

We might take these reflections a step further and argue that human beings live off the landscape—a statement that may seem hyperbolic, but that makes sense if we pay close attention. Indeed, the landscape is the source of our food: we live in the landscape and the latter activates representations and emotions within us. Our relationship with the landscape is dynamic: by changing it, we also change ourselves. It is therefore impossible to avoid entering into a relationship with the landscape. The very choice of ignoring and not ‘experiencing’ a landscape can have practical and symbolic consequences.

It is on the basis of these observations that Jean-Marc Besse wrote La Nécessité du Paysage (the Necessity of the Landscape): an essay on ecology, architecture, and anthropology, as well as an invitation to question our modes of action. In it, the French philosopher warns us against any action on the landscape: an attitude that places us ‘outside’ the said landscape, which, as mentioned above, is simply not plausible. Acting on a landscape means fabricating it, in other words starting from a preconceived idea that ignores the fact that the landscape is a living system and not an inert object. “Acting on therefore involves a twofold dualism, separating subject and object on the one hand, and form and matter on the other.”

So how might we escape this productive yet falsifying paradigm? Besse suggests a change of perspective: moving from acting on to acting with, recognising “that matter is animated to a certain extent” and envisaging it “as a space of potential propositions and possible trajectories”. The aim, in this case, is to interact “adaptively and dynamically”, to practise transformation rather than production. Acting with means engaging in ongoing negotiation, remaining open to the indeterminacy of the process, and being in dialogue with the landscape: in a word, collaborating with it.

Georg Wilson, All Night Awake, 2023

Acting with the soil

The “abiotic” dimension of soil is addressed, among other disciplines, by topography, paedology, geology, and hydrography. However, from a philosophical point of view, soil is simply the material support on which we live. This is where we construct the buildings we live in and the roads we travel on, and it is the soil that makes agriculture possible, one of the oldest and most complex fundamental manifestations of human activity. This “banal” soil is therefore in reality the focus of a whole series of essential political, social, and economic issues, and as such it raises fundamental questions. What kind of soil, water, or air do we want? The environmental disasters linked to the climate crisis and soil erosion or the consequences of the loss of fertility of agricultural and forest land call for collective responses that draw on both scientific knowledge and technical skills, as well as many political and ethical aspects.

Acting with the living

The landscapes we inhabit, travel through, and transform (including the soil and subsoil) are in turn inhabited, travelled through, and transformed by other living beings, animals and plants. In his essay Sur la Piste Animale (On the Animal Trail), philosopher Baptiste Morizot invites us to live together “in the great ‘shared geopolitics’ of the landscape”, by trying to take the point of view of “wild animals, trees that communicate, living soil that works, plants that are allies in the permacultural kitchen garden, to see through our eyes and become sensitive to their habits and customs, to their immutable perspectives on the cosmos, to invent thousands of relationships with them”. To interpret a landscape correctly, it is necessary to take into account the “active power of living beings” with their spatiality and temporality, and to integrate our relationship with them.

Acting with other human beings

A landscape is a “collective situation” that also concerns inter-human relations in their various forms. A landscape is linked to desires, representations, norms, practices, stories, and expectations, and it draws on emotions and positions as diverse as people’s desires, experiences, and interests. Acting with other human beings means acting with a complex whole that includes individuals, communities, and institutions, and drawing on the practical and symbolic—in a continuous process of negotiation and mediation.

Acting with space

Considered through the tools of geometry, space is an objective entity: its dimensions, proportions, and boundaries can be satisfactorily described. However, the space of the landscape cannot be reduced to measurable criteria. In reality, it is an intrinsically heterogeneous space: “locations, directions, distances, morphologies, ways of practising them and of investing in them economically and emotionally are not equivalent either spatially or qualitatively”. Interpreting the space of the landscape correctly therefore means remembering that “numerical” and “geometric” measurements are necessarily false, and that the set of geographies (economic, social, cultural, or personal) that make it up are neither neutral, nor uniform, nor fixed in time.

Acting with time

When we think of the relationship between landscape and time, the first image that springs to mind is that of the earth’s crust and the geological layers that make it up, or that of archaeological ruins buried beneath the surface. In short, we imagine a sort of tidy “palimpsest” of a past time, with which all relations are closed. The time of the landscape, however, should be interpreted according to more complex logics: we need only think of the persistence of practices and experiences in its context, and the fact that landscape destruction is never total: rather, it is transformation. What’s more, the time of the landscape also includes non-human time scales, such as geology, climatology, and vegetation. They are temporalities to which we are nonetheless closely linked. Thus, in reality, the landscape remains in constant tension between past and present.

“Our era,” Jean-Marc Besse concludes, “is one of a crisis of attention. […] Landscape seems to be one of the ‘places’ where the prospect of a ‘correspondence’ with the world can be rediscovered […]. In other words, the landscape […] can be seen as a device for paying attention to reality, and thus as a fundamental condition for activating or reactivating a sensitive and meaningful relationship with the surrounding world”, in other words, the necessity of the landscape.

Heidi 2.0

In 1668, Johannes Hofer described a curious physical and mental disorder that afflicted Swiss mercenaries in the service of French king Louis XIV in his medical thesis at the University of Basel. To this ailment, which has as its symptoms a state of afflicted imagination, crying fits, anxiety, palpitations, anorexia, insomnia and an obsessive longing for home, Hofer gave the name “nostalgia”: a term he coined by combining the Greek words nostos (homecoming) and algìa (pain). In later studies, the origins of nostalgia was ascribed to alleged brain damage caused by the sound of cowbells on the necks of grazing cows or to the effect of listening to mountain songs that threw young Swiss men who were far from their native soil into a prostrating state of delirium melancholicum.

The fact that the invention of the word “nostalgia” occurs precisely in the Swiss context is no coincidence: indeed, the Alpine valleys have been suffering a phenomenon of emigration and depopulation since ancient times and on several occasions, with different causes and intensity depending on the historical period. It is only in the post-World War II period, however, that the migratory phenomenon became first customary and then a real haemorrhage. The cities offered more stable employment, independent of weather conditions and seasonality, and a range of services and opportunities unparalleled by life in the valleys and the meagre income from mountain products. Local administrations saw no alternative: the choice was between investing in profitable hospitality activities linked to ski tourism, or depopulation. And with ski tourism came the rapid process of urbanisation that reshaped the mountains.

In the 1960s, therefore, an uncontrolled rush of construction of ski resorts, hotels and second homes began, responding to the conquest of the new dimension of consumption and leisure by the urban middle classes. It is precisely the relationship between the increasingly unliveable city life and the idealised representation of the Alps that drove this movement: Switzerlandalready presented itself to the first British and American tourists in the 19th centuryfrom this perspective, as evidenced by the arcadian atmosphere of Heidi, Johanna Louise Spyri’s novel which was published in 1880 and left a lasting mark on Alpine imagery. While Spyri’s novel took a complex look at the changes in Alpine ways of life as a result of industrialisation, the dominant narrative around the figure of Heidi focused on an unresolved tension between the city and the mountains, portraying Heidi’s life as healthy and “natural” when compared to the one of her sickly cousin Klara, trapped in the artificiality of urban habits. This misinterpretation reflects a distinction between nature and culture that has profoundly damaged the ability to realistically address development models in the Alps.

Alongside the concrete pouring of accommodation facilities, new asphalt roads proliferated, which, as a first consequence, reduced the capillary mobility that for centuries had united the smaller places in the valleys. As Marco Albino Ferrari recounts in his Assalto alle Alpi (Assault on the Alps), “the car, paradoxically, has made the mountains less habitable and more remote. The widespread life on the slopes has been squeezed down along the axes of the main road system, in a linear urbanism where everything must be within reach of the motor. […] The centre becomes the valley floor, next to the regimented river to prevent flooding and reduce the unusable areas of the floodplains. And it is in this mental geography, reversed with respect to previous centuries, that the valley slopes have become increasingly wild, unknown and distant. The mountain internally separates and loses those slope sides. Those mid-altitude spaces that in the indigenous experience constituted the heart of the mountain system become synonymous with high-altitude lands, where the snow allows the playful consumption of the territory vertically.”

Taking a leap forward some fifty years, we realise that the hoped-for redistribution of opportunities and prosperity over the local communities was actually a mirage destined to be reversed within a few years. The ski capitals that polarise the gaze of the general public are but a minority portion of the 6,100 municipalities in the Alps: a handful of names among an often-unknown multitude of towns and villages marked by isolation and oblivion. The depopulation that was to be avoided has taken on the dimensions of a veritable exodus. In some inland valleys, the birth of a child or the relocation of a young couple becomes a news story.

EPFL, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne, Alps model, Lausanne, Switzerland. Still from the film Alps. © Armin Linke, 2001.

On the other hand, even the most famous ski resorts are no longer safe. The glacial mass of the Alps has shrunk by 50% since the beginning of the 20th century, snowfall is increasingly sparse, and temperatures are rising. The shifting of the snow line has left the smaller, low-altitude ski resorts in a state of neglect and depression, to which they are still reacting with palliative works such as moving ski lifts a few hundred metres higher up, or the proliferation of artificial snow cannons. If operations of this kind are only palliative measures intended to plug a gap for a few more seasons, we even reach grotesque gestures such as digging a ski trail in a glacier, as recently happened at the Theodul glacier in Zermatt for the Ski World Cup. The crisis in the ski industry is being responded to with outright therapeutic overkill rather than by offering alternatives.

For the past two decades, the economy based on winter sports and or blanc (white gold, i.e. snow) has been going through a crisis, along with urban-based consumption models that underpinned it. A new approach to the mountains is emerging, that of “Alpine minimalism”, which prefers the frugality of the mountain hut and so-called slow tourism in an often anti-modernist key to the high-altitude resort. While this new transformation has the merit of avoiding the dysfunctions associated with the sharp division between high and low season, once again it is a distortion. The appearance of old farm implements on the facades of chalets (not always locally sourced), copper cauldrons hanging in restaurants, traditional clothes to dress waiters, what the anthropologist Annibale Salsa has called “proximity exoticism”, is born, or rather a posturing and anti-technological form of authenticity—Heidi 2.0.

This approach is paradoxical even at a brief glance. In Fragments d’une montagne, Nicolas Nova describes the landscape of Conches, in the upper Valais: “In this corner of the Alps, where the Rhône is still no more than a small river close to its source, the valley is criss-crossed by a host of networks: overhead electricity cables, roads, tunnels and a summit track that is only accessible in summer, the Matterhorn-Gotthard Bahn railway (which carries both passengers and vehicles to avoid the Furka Pass), cross-country ski trails or snowshoe trails studded with orange Swissgas signs indicating the presence of the underground gas pipeline. It’s as if we’re looking at a machine-mountain, with a technical framework that transforms the environment into a productive infrastructure. A Victor Frankenstein-style hybrid of geology and electricity pylons, cavities, rails, dams, bunkers of varying degrees of strength, cable cars, pipes, roads, mobile phone masts and rivers with rectified courses. The mountain-machine, a recurring motif in the Alps, with watercourses, valley bottoms and reliefs covered with all this equipment”.

The anthropization of the Alps is not a new phenomenon: for thousands of years the human species has inhabited this mountain range, ingeniously coping with the scarcity of resources and the complications of life on the slopes, finding specific solutions to coexist in symbiosis with the other species in its ecosystem. Today, due to the thinning out of traditional farming and animal husbandry practices in favour of tourism, the extent of wilderness in the Alps is as great as it was in the Middle Ages. But in spite of this, the balance of the past has broken down, if the public narrative is at the service of those who are convinced that the Alps need to be “valued”—and are not a value in themselves. How can we once again look at the mountains honestly and realistically? How can we return to inhabiting rather than exploiting them? If a path is not walked, it disappears within a short time. The degradation of trails is not caused by overuse, but by oblivion.

Learning from mould

Reading

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Learning from mould

Physarum polycephalum is a bizarre organism of the slime mould type. It consists of a membrane within which several nuclei float, which is why it is considered an “acellular” being—neither monocellular nor multicellular. Despite its simple structure, it has some outstanding features: Physarum polycephalum can solve complex problems and move through space by expanding into “tentacles,” making it an exciting subject for scientific experiments.

The travelling salesman problem is the best known: it’s a computational problem that aims to optimise travel in a web of possible paths. Using a map, scientists at Hokkaido University placed a flake of oat, on which Physarum feeds, on the main junctions of Tokyo’s public transportation system. Left free to move around the map, Physarum expanded its tentacles, which, to the general amazement, quickly reproduced the actual public transport routes. The mechanism is very efficient: the tentacles stretch out in search of food; if they do not find any, they secrete a substance that will signal not to pursue that same route.

We are used to thinking of intelligence as embodied, centralised, and representation-based: Physarum teaches us that this is not always the case and that even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating.

Putting Off the Catastrophe

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously? How can we overcome the apathy of our eternal present? The following article is taken from MEDUSA, an Italian newsletter that talks about climate and cultural changes. Edited by Matteo De Giuli and Nicolò Porcelluzzi in collaboration with NOT, it comes out every second Wednesday and you can register for it here. In 2021, MEDUSA also became a book.

There is no alternative was one of Margaret Thatcher’s slogans: wellbeing, services, economic growth… are goals achievable exclusively by doing things the free market way. 40 years on, in a world built on those very election promises, There is no alternative sounds more like a bleak statement of fact, a maxim curbing our collective imagination: there is no alternative to the system we’re living in. Even when we’re hit by crisis, in times of unrest, exploitation and inequality, the state of affairs finds us more or less defenceless. There’s no escape – or we can’t see it: our room for manoeuvre has been fenced off.

Why can’t we take global warming seriously? Because it’s one of those complex systems that operate, as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams affirm in their Inventing the Future, “on temporal and spatial scales that go well beyond the bare perceptual capacities of the individual” and whose effects “are so widespread that it’s impossible to exactly collocate our experience within their context”. In short, the climate problem is also the result of a cognitive problem. We are lost in the corridors of a vast and complex building in which we see no direct and immediate reaction to anything we do and have no clear moral compass to help us find our way.

It was to pursue these issues further that I decided to read What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming (hereafter WWTAWWTNTAGW) by Norwegian psychologist and economist Per Espen Stoknes, a book I’d been putting off reading for some time for a series of reasons that turned out to be only partially valid. First of all, there was my vaguely scientist prejudice: despite being interested in the issue, I find that the back cover of WWTAWWTNTAGW sounds more like front flap blurb for some self-help publication rather than for a serious work of popular science. I quote: “Stoknes shows how to retell the story of climate change and at the same time create positive, meaningful actions that can be supported even by negationists”. Then there was the title, WWTAWWTNTAGW, a cumbersome paraphrase of a title that is already, in itself, the most ferociously paraphrased in the history of world literature. And lastly — still on the surface only – there was the spectre of another book by Per Espen Stoknes, published in 2009, the mere cover of which I continue to find insurmountably cringeful: Money & Soul: A New Balance Between Finance and Feelings.

Laying aside, for the moment at least, the prejudices that kept me away from WWTAWWTNTAGW, I discovered a light-handed book that raises various interesting points. In short: why does climate change, our future, interest us so little? Why do we see it as such an abstract and remote problem? What are the cognitive barriers that are sedating, tranquillizing and preventing us from having even the slightest real fear for the fate of the planet? Stoknes identifies five, which can be summed up more or less as follows:

Distance. The climate problem is still remote for many of us, from various points of view. Floods, droughts, bushfires are increasingly frequent but still affect only a small part of the planet. The bigger impacts are still far off in time, a century or more.

Doom. Climate change is spoken of as an unavoidable disaster that will cause losses, costs and sacrifices: it is human instinct to avoid such matters. We are predictably averse to grief. Lack of practical solutions on offer exacerbates feelings of impotence, while messages of catastrophe backfire. We’ve been told that “the end is nigh” so many times that it no longer worries us.

Dissonance. When what we know (using fossil fuel energy contributes to global warming) comes into conflict with what we’re forced to do or what we end up doing anyway (driving, flying, eating beef), we feel cognitive dissonance. To shake this off, we are driven to challenge or underestimate the things we are sure about (facts) in order to be able to go about our daily lives with greater ease.

Denial. When we deny, ignore or avoid acknowledging certain disturbing facts that we know to be “true” about climate change, we are shielding ourselves against the fear and feelings of guilt that they generate, against attacks on our lifestyle. Denial is a self-defence mechanism and is different from ignorance, stupidity or lack of information.

Identity. We filter news through our personal and cultural identities. We look for information that endorses values and presuppositions already inside our minds. Cultural identity overwrites facts. If new information requires us to change ourselves, we probably won’t accept it. We balk at calls to change our personal identities.

There are obviously hundreds of other reasons why we still hold back from a strategy to mitigate climate change: economic interests, the slowness of diplomacy, conflicting development models, the United States, India, sheer egoism, “great derangement” and all the other things we’ve come to know so well over the years. But Per Espen Stoknes empirically suggests a way forward. Catastrophism and alarmism don’t work. We need to find a different tone to dispel the apathy of our eternal present.

Image: The Grosser Aletsch, 1900 Photoglob Wehrli © Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung und Fotoarchiv/ 2021 Fabiano Ventura – © Associazione Macromicro.