laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

media

filter media by

-

Reading

-

Video

-

Audio

- press

- All media

The Life of Lines

Reading

Humans make lines when walking, talking, or gesturing.

Sur le seuil

Transforming Knowledge

Reading

Every knowledge is rooted in specific contexts and experiences.

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

Cruel optimism

Reading

“Cruel optimism”, according to Lauren Berlant, refers to what grates on our desires and prevents us from carrying on as hoped

least

The Nest

Reading

A poetic reflection by Gaston Bachelard on the nest as a symbol of intimacy, refuge, and imagined worlds.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Everything Flows

Reading

Life relies on a delicate synchronization between the rhythms of living beings and the cycles of the Earth.

Faire commun

Vivre le Rhône

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Walking in Taranto

Reading

To encounter a city through walking.

least

The “life” of objects

Reading

Matter should not be considered as passive and inert, but as infused with intrinsic vitality.

d'un champ à l'autre / von Feld zu Feld

Peau Pierre

Emergency and Cocreation

Reading

An interview with architect Antonella Vitale.

Sur le seuil

Devenirs buissons

Living Soil

Reading

Although we walk on it every day, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

Fences and Power

Reading

The fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

Arpentage

Faire commun

d'un champ à l'autre / von Feld zu Feld

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Autumn in the Garden

Reading

“We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn”.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

How happy is the little stone

Reading

Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life.

Peau Pierre

Arpentage

Faire commun

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Ô noble Green

Reading

The «Ignota Lingua» by Hildegarde of Bingen.

CROSS FRUIT

Common Dreams

Faire commun

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Reading

Yves Citton discusses commons, negative commons, and sub-commons with us.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Experiencing the Landscape

Reading

The complexity of the term ‘landscape’ can best be understood through the concept of ‘experience’.

Vivre le Rhône

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Heidi 2.0

Reading

The Alps and “proximity exoticism.”

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Listenting to the Sourdough

Reading

An interview with the artist and scholar Marie Preston on cooperative practice and including the more-than-human.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

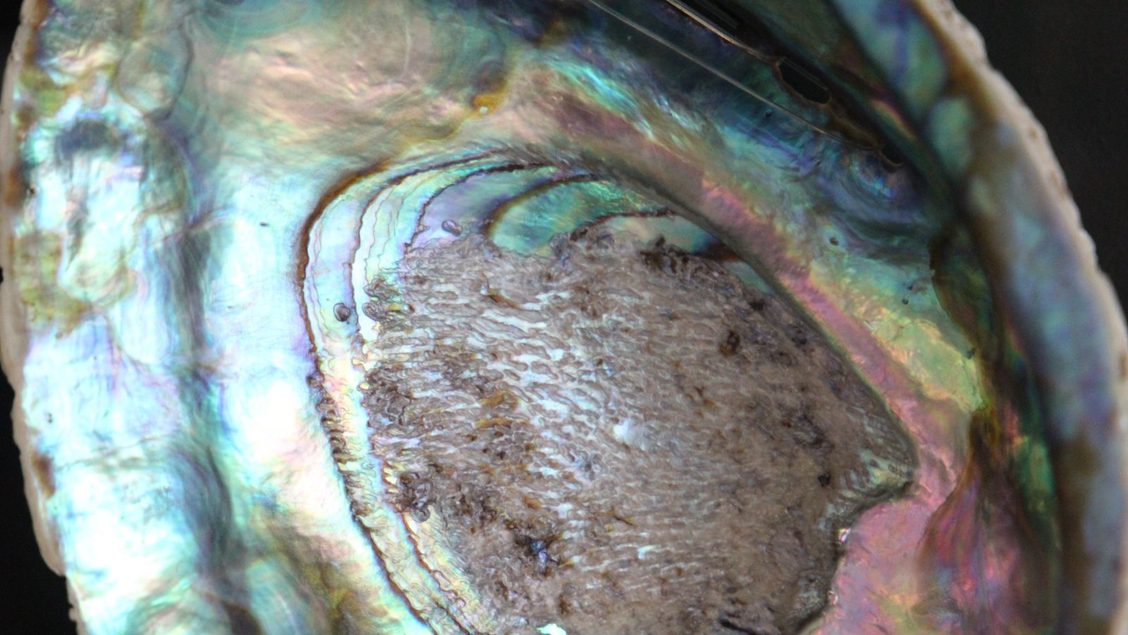

Mineral Life

Reading

Recognising our entanglement with geological processes.

Peau Pierre

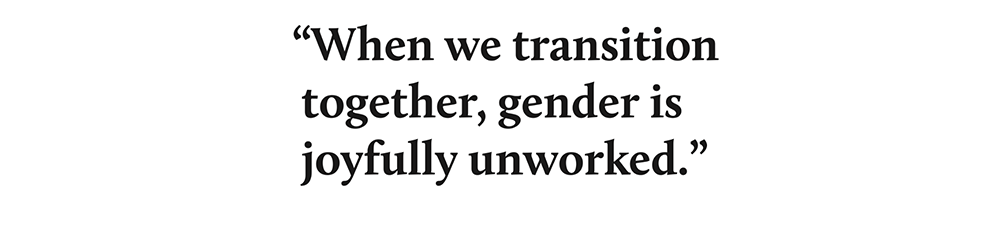

Rethinking Transition

Reading

An interview with Denise Medico.

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Video

An urban ecology project that involves citizens in the design, creation and maintenance of an orchard.

CROSS FRUIT

Vivre le Rhône: part 3

Video

River Guardians

Vivre le Rhône

The Sacrifice Zone

Reading

“One day, at the Ironbound Community Corporation, we smelled something pungent”.

least

The Gesamthof recipe: A Lesbian Garden

Reading

The Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, a garden without the idea of an end result.

CROSS FRUIT

Peau Pierre

Peau Pierre: an audio capsule

Audio

“When our skins finally touch, water is the intermediary in this encounter”.

Peau Pierre

Wild Bread

Reading

An essay about the experience of hunger in Europe in the modern age.

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 03

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 02

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

Spillovers

Reading

A sci-fi essay and sex manual created by Rita Natálio.

Peau Pierre

Vivre le Rhône: part 2

Video

When art meets law.

Vivre le Rhône

Guardians of Nature

Reading

An interview to Marine Calmet, lawyer specialised in environmental law and Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Vivre le Rhône

Bodies of Water

Reading

Embracing hydrofeminism.

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

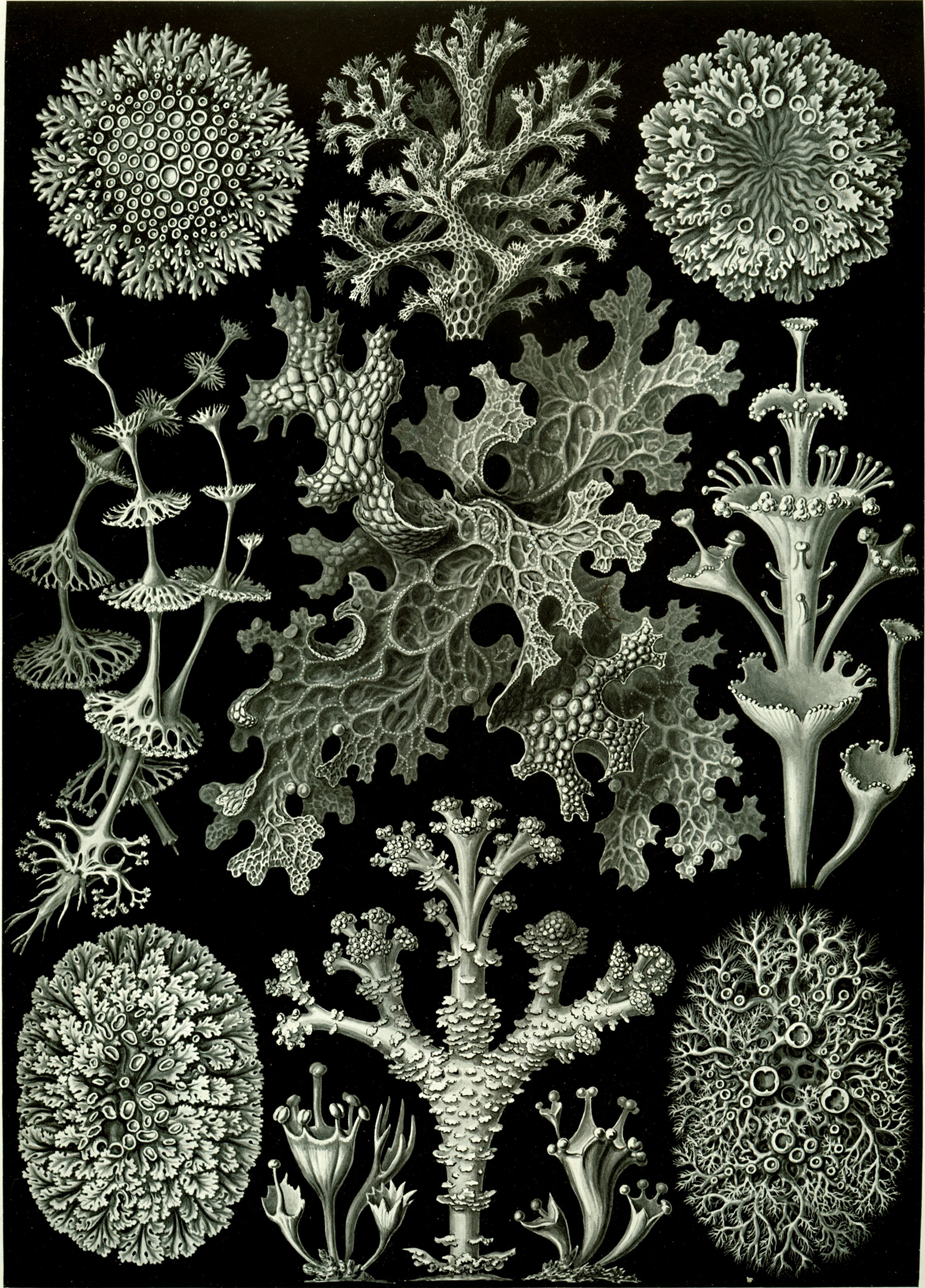

Intimity Among Strangers

Reading

Lichens tell of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option

Common Dreams

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 01

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

A Sub-Optimal World

Reading

An interview with Olivier Hamant, author of the book “La troisième voie du vivant”.

Common Dreams

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Putting Off the Catastrophe

Reading

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously?

Common Dreams

Vivre le Rhône

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

GLOSSARY OF TRANSITION (T — T) by Ritó Natálio

Reading

A collective, ecotransfeminist speculative fiction.

Peau Pierre

A urge to do something

Reading

An interview to climate activist Myriam Roth.

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: part 1

Video

Meet the Rhône and Natural Contract Lab

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Video

The video of the project Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School.

Common Dreams

The Life of Lines

“As walking, talking, and gesticulating creatures, human beings generate lines wherever they go.” This simple yet incisive observation opens Lines: A Brief History, an essay in which anthropologist Tim Ingold lays the groundwork for what he calls a “comparative anthropology of the line.” The book sets out to trace the presence and purpose of lines across a vast range of human activities, revealing how—through varied historical, cultural and geographical lenses—they disclose the ways in which human beings have imagined, enacted and reshaped their modes of life and thought over time.

Ingold’s reflection is grounded in an anthropological approach that places lived practice at its heart. True to this spirit, he invites readers to undertake a small experiment: to imagine — or better still, to draw — a long, meandering line across a sheet of paper, without any specific aim, a line he likens to being “out for a walk.” He then proposes to reproduce this same line not through the fluid continuity of gesture, but by translating it into a series of evenly spaced dots, that are then joined together. The resulting image may appear much the same, yet the embodied experience of producing it could hardly be more different. One is a gesture surrendered to the fluidity of movement; the other, a deliberate act of juxtaposition and connection, demanding a distinct temporality, attention and corporeality. It is in this lived difference—prior even to any formal one—that Ingold’s contrast between wayfaring and transport comes most sharply into view.

These two ways of drawing a line correspond to two ways of moving through the world and of experiencing space: on the one hand, the itinerant journey, or wayfaring; on the other, the directed motion of transport. In the first, the traveller is not compelled by the need to reach a predetermined destination, for the path itself — potentially infinite — holds the very meaning of movement. This is not to suggest aimless wandering. As hunter-gatherer groups demonstrate, one may travel with attentiveness rather than intent: guided by landmarks, attuned to the fruits to be gathered, the traces leading to new resources, the unexpected opportunities along the way, and even the pauses for rest that form an integral part of the journey. In this view, paths are not mere lines connecting two points; they are gradually shaped, becoming corridors of inscription—lived spaces continually rewritten by those who traverse them.

Transport, by contrast, is defined from the outset by a fixed destination and by the aim of moving people or goods “in such a way as to leave their basic natures unaffected.” What matters here is not the lived experience of the journey, nor any attentiveness to what unfolds along the way, but rather the efficiency of transfer from one place to another — so that any personal transformation that travel might provoke is systematically excluded. Intermediate stages, in this logic, are not moments of pause, observation or reinterpretation, but mere functional intervals, measured in terms of technical activity or completion. Where the wayfarer is always somewhere — rooted in a relationship of presence with the environment they inhabit — the passenger in transport, when neither at the point of departure nor at the point of arrival, is nowhere: suspended in transit, stripped of situated experience. Ingold aptly summarises this condition, calling it “the dissolution of the intimate bond that, in wayfaring, couples locomotion and perception.”

This distinction also finds expression in spatial metaphors. The wayfarer, moving along, weaves an irregular mesh that overlaps and intertwines with other lines, forming a fabric that embodies a way of dwelling in the world. Transport, by contrast, conjures a network of interconnected points, in which paths are reduced to functional segments linking predetermined nodes — reflecting less an experience of dwelling than a logic of occupation. These two perspectives are not simply variations on a theme; they reveal profoundly different conceptions of the relationship between movement and space.

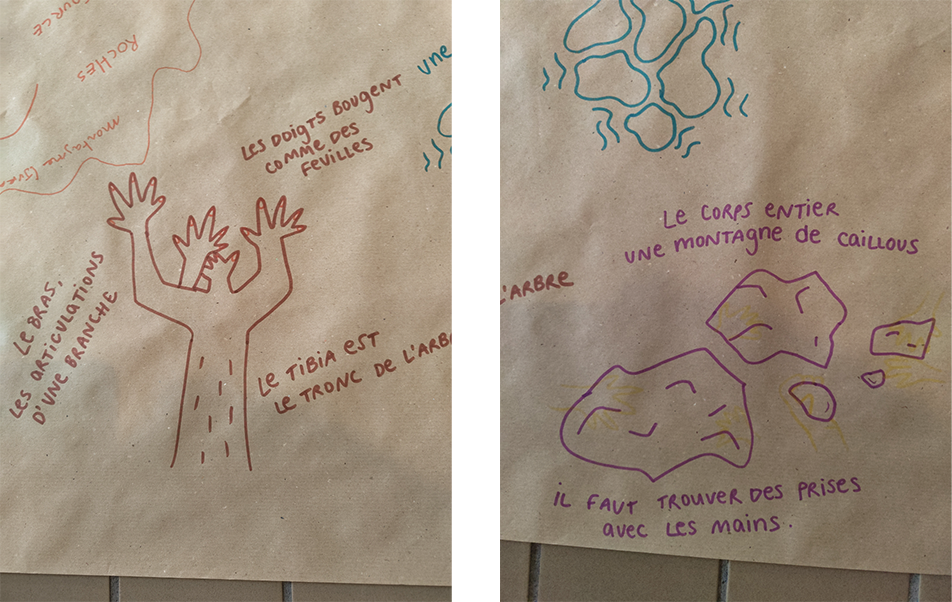

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Likewise, representations of space bear the imprint of this distinction. When we sketch a map to give someone directions, what appears on paper is never a mere objective transposition, but the outcome of lived experience — enriched by our stories, memories and the gestures that accompany our explanations. Each mark bears witness to a journey already taken, traced along a “path of observation.” In this sense, lines are not simple graphic signs but traces of movement—the very essence of the sketch, for they both orient and evoke a tangible relationship with the terrain. By contrast, on a modern map, the line loses its narrative and experiential charge, assuming instead a symbolic and normative role: it signifies roads, railways and physical or administrative boundaries, embodying “an appropriation of the space surrounding the points that the lines connect or (…) that they enclose.” The result is a form of cartographic knowledge that does not emerge from the embodied experience of movement, but is constructed by linking distant, abstract points—fragmenting experience and silencing the stories it might tell. It is not knowledge that moves, but knowledge assembled: functional to a system of occupation and control rather than to a process of dwelling and observation. This way of representing space also permeates urban design, structured by limits, predefined routes and thresholds — features that the everyday practices of inhabitants continually subvert or reinterpret.

At this juncture, Ingold makes a decisive turn in his argument. Beneath the different ways of moving through and representing space, he discerns two distinct ways of conceiving knowledge. He shows that our understanding of knowing is inseparable from the gestures and trajectories through which we relate to the world: every form of knowledge, whether explicit or implicit, is grounded in a way of moving, walking or orienting oneself. In contemporary Western societies, the conception of movement as linear, goal-oriented and efficient has gradually shaped a corresponding form of knowledge — one constructed through the linking of fixed points, through processes of organisation, classification and articulation. This is knowledge built by juxtaposition, privileging stability and measurement over the fluidity and contingency of lived experience. To know, in this view, is to accumulate data and to establish abstract relations among discrete elements — a logic of control and planning.

Conversely, conceiving movement as a continuous and open journey invites us to reimagine knowledge as a living process, formed in direct contact with the world, within the temporality of gesture and the reciprocity of perception. Knowing no longer means dominating or representing from without but dwelling within an environment: allowing oneself to be moved by its rhythms and to respond to its invitations. In this light, knowledge emerges as a practice of attention and participation—a dynamic entanglement of perception, memory and invention. It becomes a path of thought which, like the wayfarer’s journey, does not seek a final destination but continually renews itself through its very unfolding.

In this sense, representations of space are not neutral images of the world, but genuine cognitive and relational models: they both mirror and shape particular ways of thinking and living. Contemporary maps and diagrams, by reducing space to a network of functional connections, express a form of knowledge that separates the observer from the world, imposing an external and overarching point of view. Yet the experience of dwelling — woven from everyday gestures, diversions and encounters — reveals an opposing logic: not one of distance, but of proximity; not one of occupation, but of involvement.

The notion of a “pure transport” — a movement linking two points without leaving any trace of transformation — is, for Ingold, an illusion, much like the belief in neutral, disembodied knowledge. One cannot know without being involved, just as one cannot traverse a space without altering it or being altered in return. For Ingold, to know is always to inhabit the world: to engage with it through practice, attention and gesture, weaving with the living a fabric of correspondences and shared stories. It is within this reciprocity, rather than within abstraction, that what he calls the “ecology of life” takes shape: a form of knowledge that does not merely connect points, but follows the very lines of the living, opening itself to the continuity and unpredictability of the inhabited world.

Transforming Knowledge

Knowledge – and scientific knowledge in particular – is often perceived as something neutral, universal and abstract. This illusion, which lends it authority and prestige, conceals the fact that all knowledge is rooted in specific contexts and embodied in experiences. Every act of research is born of an encounter with matter and with others. It is within this tension that many contemporary theories have mounted a radical critique of the dominant view, inviting us instead to think of knowledge as an embodied, relational experience.

In Situated Knowledges, Donna Haraway dismantles the fiction of “objective” science. She reminds us that every gaze is always partial and situated: there is no neutral point of view, only embodied perspectives, i.e. perspectives that carry responsibility and call for a “science project that offers a more adequate, richer, better account of a world, in order to lie in it well and in critical, reflexive relation to our own as well as others’ practices of domination and the unequal parts of privilege and oppression that make up all positions. In traditional philosophical categories, the issue is ethics and politics perhaps more than epistemology.” For Haraway, objectivity does not mean hypocritically erasing partiality but rather making it explicit and owning up to the relationships that make it possible. This shift transforms science into what she calls a “successor science”: no longer the abstract possession of universal truths, but a situated practice that acknowledges its grounding in bodies and histories.

In bell hooks’ pedagogy, this principle takes on a concrete form. In Teaching to Transgress, the classroom is not portrayed as a neutral space for the transmission of knowledge, but as a place shaped by identities, emotions, desires and reciprocal relations. Teaching becomes a “practice of freedom”: not merely the communication of content, but the opening up of a space where lived experience rightfully enters the learning process and where pedagogical formats are continually re-examined and co-created collectively within what hooks calls the learning community. In contrast to the academic ideal of aseptic, disembodied didactics, hooks – writing from her position as a Black woman in a white university – asserts the value of the body, of personal histories and of process itself as necessary conditions of learning. For hooks, the aim of teaching is to guide action and reflection in order to transform the world, to convert the will to know into a will to become.

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Another influential position in this regard can be found in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s writings on Amerindian perspectivism, which he defines as the idea “that the world is inhabited by different kinds of subjects or persons, human and non-human, who apprehend reality from distinct points of view.” At first glance, this might sound like relativism, but in fact it overturns the relativist hypothesis: it is not that there is a single physical “nature” interpreted by a plurality of cultures. For perspectivism, on the contrary, there is a single culture, shared by all beings, including non-human animals, who see themselves as persons and participate in sociality and belief. What exists instead is a multiplicity of “natures”, since each type of being perceives and inhabits a different world. Thus, jaguars see blood as manioc beer: what might appear to us as an objective given is, within this cosmology, the result of an embodied perspective. One consequence of this ontology is a reversal of the Western conception of culture: “creation-production is our archetypal model of action (…) while transformation-exchange would probably fit better the Amerindian and other non-modern worlds. The exchange model of action supposes that the other of the subject is another subject, not an object; and this, of course, is what perspectivism is all about.”

With Making by Tim Ingold, the discourse on embodied knowledge is tightly interwoven with the experience of making. Rather than the accumulation of data, he values the cultivation of a sensitive, bodily attention, “against the illusion that things can be ‘theorised’ independently of what is happening in the world around us.” From this perspective, “the world itself becomes a place of study, a university that includes not just professional teachers and registered students, dragooned into their academic departments, but people everywhere, along with all the other creatures with which (or whom) we share our lives and the lands in which we – and they – live. In this university, whatever our discipline, we learn from those with whom (or which) we study. The geologist, for example, studies with rocks as well as with professors; he learns from them, and they tell him things. Likewise, the botanist studies with plants and the ornithologist with birds.” Hence his critique of traditional academic forms, which claim to explain the world as if knowledge could be constructed after the fact, by excluding the body and practice. For Ingold, by contrast, thinking and making are inseparable: “materials think in us, as we think through them.” It is in this spirit that the introduction of artistic and manual practices into his teaching plays a central role: it demonstrates that knowledge arises from the experimenting body, in correspondence with materials that actively take part in transformation. The ultimate aim is not to document from the outside, but to transform: if learning changes us, it must also be given back to the world, opening up other possibilities of relation.

These diverse voices converge on a single point: knowledge is never detached from the world, but takes shape through its interaction with bodies, materials and relationships. This is not to deny the rigour or the importance of academic institutions, but to stress that knowledge is diminished when it erases the embodied and situated conditions from which it arises. Focusing on these dimensions is to transform knowledge, from an instrument of domination into an ecological practice of coexistence, where disciplinary boundaries blur and description gives way to collective, transformative experience. It is within this space of research and experimentation that least positions its work: approaches that bring together transdisciplinary teams in which everyone has an equal place and commits to crossing the frontiers of their own discipline; approaches that privilege process over outcome; and approaches that, through artistic practice, open new ways of developing and transmitting knowledge.

Cruel optimism

“A relation of cruel optimism exists when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing. It might involve food, or a kind of love; it might be a fantasy of the good life, or a political project. It might rest on something simpler, too, like a new habit that promises to induce in you an improved way of being. These kinds of optimistic relation are not inherently cruel. They become cruel only when the object that draws your attachment actively impedes the aim that brought you to it initially.”

These are the opening words of Cruel Optimism, a book by theorist Lauren Berlant that, in recent years, has become a key reference for anyone thinking seriously about affect, desire and precarity.

Who hasn’t, at least once, believed that working harder than necessary would help us get ahead? Or that a toxic relationship was better than being alone? Or that political commitment, on its own, could truly change things? All these promises eventually start to creak. And behind that creaking, Berlant identifies a deeper, more pervasive feeling that runs through many contemporary lives: the impasse – a condition in which we keep moving forward without really knowing where we’re going, where we’re surviving more than living, where change is both longed for, feared and always somehow postponed.

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

But Berlant doesn’t stop at diagnosis. They invite us to pay attention to the micro-tactics through which people try to survive within the impasse. They call these forms “self-interruption”: tiny gestures like eating erratically, compulsively scrolling, binge-watching endless series, procrastinating – things we often regard as bad habits or self-sabotage. Yet in Berlant’s reading, these are also reprieves, pauses in the relentless push for productivity, fleeting moments where the self finds shelter; acts that, while they may not change the world, express a desire to keep going and in that very persistence, carry a quiet political force.

To live in an exhausting world and somehow manage – even just for today – not to fall apart, is already a form of resistance.

Perhaps, then, we might learn something from this stance: to be gentler with ourselves, to allow space for rest, for emptiness, for pause. To accept doing nothing, from time to time, can be an act of care. And it is also a way of desiring a more liveable world.

The Nest

Here is an excerpt from The Poetics of Space by 20th-century French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. In this work, Bachelard explores spaces of human intimacy – houses, drawers, nooks, nests – not as physical objects, but as places imbued with life and imagination. The passage featured is a poetic and thoughtful meditation on the nest, viewed as a vital refuge, the centre of a universe that is both real and imagined.

It is the living nest, however, that might introduce a phenomenology of the real nest, the nest found in nature, which becomes, for a fleeting moment (and the word is not too grand), the centre of a universe, the marker of a cosmic situation. I gently lift a branch, the bird is there, brooding on its eggs. It does not fly away. It only trembles, slightly. I tremble at making it tremble. I fear that the nesting bird knows I am a man, that being who has lost the trust of birds. I remain still. Slowly – so I imagine – the bird’s fear and my fear of causing fear subside. I breathe more easily. I let the branch fall back. I’ll return tomorrow. But today, I carry a quiet joy: the birds have built a nest in my garden.

And the next day, when I return, walking even more softly, I see, at the bottom of the nest, eight eggs of a pale pinkish white. My God! How small they are! How tiny a hedge bird’s egg is!

There is the living nest, the inhabited nest. The nest is the bird’s home. I’ve long known this, it’s long been said to me. It’s such an old truth that I hesitate to repeat it, even to myself. And yet I have just relived it. I recall, with a clear and simple memory, those rare moments in life when I have discovered a living nest. How few and precious are such true memories in a lifetime!

I now fully understand Toussenel’s words:

“The memory of the first bird’s nest I found on my own has remained more deeply etched in my mind than that of the first Latin prize I won at school. It was a lovely greenfinch’s nest with four grey-pink eggs, traced with red lines like a symbolic map. I was struck on the spot by an unspeakable joy that rooted me there for over an hour. It was my calling that chance revealed to me that day.”

What a beautiful passage for those of us seeking the sources of our earliest fascinations! When we resonate, even from afar, with such a shock, we better understand how Toussenel could integrate, in both life and work, the harmonic philosophy of Fourier, adding to the bird’s life an emblematic dimension, a universe of meaning.

And even in ordinary life, for someone who lives among woods and fields, the discovery of a nest is always a fresh emotion. Fernand Lequenne, the plant lover, walking with his wife Mathilde, spots a warbler’s nest in a blackthorn bush:

“Mathilde kneels down, reaches out a finger, brushes the fine moss, holds her hand there, suspended…

Suddenly, I shudder.

I’ve just discovered the feminine meaning of the nest, perched in the fork of two branches. The bush takes on such human significance that I cry:

– Don’t touch it, whatever you do, don’t touch it!”

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Toussenel’s shock, Lequenne’s shudder, both carry the unmistakable mark of sincerity. We echo them in our reading, since it is often in books that we experience the thrill of “discovering a nest.” Let us then continue our search for nests in literature.

Here is an example where a writer intensifies the nest’s role as home. We have borrowed it from Henry David Thoreau. In his writing, the entire tree becomes, for the bird, the vestibule of its nest. Already, the tree that shelters a nest partakes in the mystery of the nest. For the bird, the tree is a refuge.

Thoreau shows us the woodpecker making a home of the whole tree. He compares this act of possession to the joyful return of a family moving back into a long-abandoned house: “Just as when a neighbouring family, after a long absence, returns to their empty home, I hear the joyful sounds of voices, the laughter of children, and see smoke rising from the kitchen. The doors are flung wide open. The children race through the hall, shouting. So too, the woodpecker darts through the maze of branches, drills a window here, bursts out chattering, dives elsewhere, ventilates the home. It calls out from top to bottom, prepares its dwelling… and claims it.”

Thoreau gives us, all at once, the nest and the house unfolding. Isn’t it striking how his text breathes in both directions of the metaphor: the joyful house becomes a vibrant nest – and the woodpecker’s trust, hidden in its tree-nest, becomes the confident claiming of a home.

Here, we go beyond mere comparison or allegory. The “proprietor” woodpecker, appearing at the tree’s window, singing from its balcony, a critical mind might call this an “exaggeration.” But the poetic soul will be grateful to Thoreau for expanding the image, giving us a nest that reaches the size of a tree.

A tree becomes a nest the moment a great dreamer hides in its branches. In Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, Chateaubriand shares such a memory: “I had built myself a perch, like a nest, in one of those willows: there, suspended between earth and sky, I would spend hours with the warblers.”

Indeed, when a tree in the garden becomes home to a bird, it becomes dearer to us. However hidden, however silent the green-clad woodpecker may be among the leaves, it becomes familiar. The woodpecker is no quiet tenant. And it’s not when it sings that we think of it, but when it works. All along the tree trunk, its beak strikes the wood with resonant blows. It often vanishes, but its sound remains. It’s a labourer of the garden.

And so, the woodpecker has entered my sound-world. I’ve turned it into a comforting image. When a neighbour in my Paris flat hammers nails into the wall late into the evening, I “naturalise” the noise. True to my method of making peace with anything that disturbs me, I imagine myself back in my house in Dijon, and I say to myself: “That’s just my woodpecker, working away in my acacia tree.”

Everything Flows

As part of Faire commun – a shared ecology project in Parc Rigot – least invites you to reflect on the rhythms that flow through living beings, places and time itself. “Faire commun” also means “making time together”: exploring how our lives align – or fall out of step – with the cycles that surround us. This text invites readers to attune to the world’s many pulses, imagining new forms of sensitive coexistence.

At Parc Rigot, students, researchers and artists came together to resonate with the land – an interdisciplinary and sensory exploration aimed at revealing the unique rhythms of the landscape, its lifeforms and its uses. By observing the park’s centuries-old oaks, its passers-by and its pond, they highlighted how each element vibrates at its own tempo – sometimes steady, sometimes chaotic – composing a shared, living score.

The word “rhythm” comes from the Greek verb rhéô, meaning “to flow”. In Greek philosophy, panta rhei (“everything flows”) captures the thought of Heraclitus of Ephesus, philosopher of perpetual change: all is in constant transformation, like a river whose waters move constantly, so much so that “one can never step into the same water twice” …

Water, indeed, is at the heart of our first experience of rhythm. Even before birth, we perceive sound through amniotic fluid: heartbeats, breath, blood flow. Only low, rhythmic sounds travel through this liquid medium. After birth, part of this water remains in us: the inner ear, still filled with fluid, senses the world’s vibrations. This original water holds a deep memory of rhythm and time within us. Perhaps that is why Rigot’s pond, nestled at the base of the park, acts as a sensory magnet: it draws the eye, attracts wildlife and becomes a focal point where human and non-human rhythms converge across the day.

Humanity has long sought to measure time. One of the earliest known instruments is a water clock (clepsydra) from the 14th century BCE, discovered in the Karnak Temple in Egypt. Two vessels, connected by a small opening, allowed time’s flow to be measured steadily. At Rigot, the oaks planted on the western side play a similar role: silent timekeepers, inscribing memory into their bark year after year.

In soundscapes little touched by human activity, most sounds follow predictable rhythms. Birdsong, the rustle of wind in leaves, the soft lapping of water – these recurring motifs are registered by living beings as familiar and non-threatening. Such regularity soothes and stabilises the soul. In contrast, abrupt noises – construction, crowds, traffic – disrupt sensory balance, triggering alarm. Auditory rhythm is thus a key element of perceptual stability.

Rhythm is essential to how every species hears. Neurons in the ear and brain activate only when sound frequencies align with a reference rhythm. In the 1960s, Hungarian researcher Péter Szőke slowed down birdsong to reveal its hidden complexity, unheard by the human ear. This attention to the invisible and the subtle informs the sensory work carried out in Parc Rigot: to listen, to slow down, to observe what often slips beneath the surface of perception.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

For living beings, time unfolds on three levels: internal rhythm, synchronisation with environmental cycles and coordination with others. Internal rhythm is fine-tuned by external signals – zeitgebers (“time-givers”) – such as light, temperature and seasons. For migratory birds, the memory of thawing snow, the length of day and the behaviour of other species help determine when to depart for breeding grounds.

Time, then, is not solely personal, it is also social. In a beehive, nurse bees maintain a constant internal rhythm, while foragers adjust to the timing of flower openings. The coordination of these internal clocks generates a shared rhythm, or a collective time.

Human societies, too, maintain diverse and complex relationships with time. In many Indigenous cultures, time is tied to local rhythms of land, animals and landscapes. Among Sámi reindeer herders, for instance, the concept of jahkodat holds that each year is unique: migration depends on the snow thawing, pasture health and other shifting factors. “One year is not the sister of the next”, a Sámi proverb says: each cycle demands careful attention and constant adaptation.

Today, globalisation has dulled this seasonal sensitivity. Yet seasonality is not universal. Some regions know four seasons; others alternate between wet and dry. In Nagori, Ryoko Sekiguchi notes that Japan traditionally divides the year into 24 seasons, or even 72 micro-seasons. This refined sense of time shapes language itself, with words and haikus linked to precise moments, weaving culture, climate and expression together.

But so-called “objective” time is also a human invention. In Austerlitz, W.G. Sebald reminds us that while time is tied to the stars, it ultimately rests on convention. Even the solar day varies; to stabilise our clocks, we invented a “mean sun” – a fictional body whose steady motion serves as a reference.

The standardisation of time intensified in the 19th century with the advent of railways. To coordinate schedules, time zones were imposed, overriding the diversity of local times. The world entered an era of strict synchronisation, a standardisation that now coexists with the ecological and temporal dissonance we face.

For non-humans, life depends on a fine attunement between living rhythms and Earth’s cycles. Climate change is unsettling these balances. At Rigot, as elsewhere, seasons shift, temperatures rise, blooms and migrations fall out of sync, disrupting biological clocks. This breakdown threatens the reproduction, food sources and survival of many species. When life’s rhythms fall out of step with Earth’s cycles, the very balance of life begins to waver.

In the face of growing dissonance between human time and living time, Faire commun calls for a sensitive reorientation: to slow down, to listen, to live together. Parc Rigot becomes a shared learning ground, where we can explore new ways of inhabiting time, neither linear or productivist, but rather cyclical, porous, attuned to what grows, changes or disappears. By reconciling Earth’s many temporalities, this project sketches the outline of an inhabitable future.

Walking in Taranto

This text was written by the artist Martin Reinartz as part of least’s research residency program in Southern Europe. This program aims to create dialogue between artists, researchers, and communities around ecological and social issues, through periods of immersion in territories strongly affected by the consequences of the environmental crisis. Martin Reinartz’s residency in Taranto, made possible thanks to our ongoing collaboration with the local collective Post Disaster, is part of this approach.

November 2024.

I’m going to Taranto as a guest artist with the Post Disaster collective of architects and urban planners. I know nothing about the city other than the stories I’ve heard about it. I don’t want to know anything more, I don’t want to pre-empt anything.

People might think that it’s unjustifiable, someone coming without a plan. I reassure myself. My plan is this total absence of a plan. I simply want to ask them, those who will welcome me, that we walk together in their city. Just two at a time. That they take me to places that are important to them, that they love. No matter whether it’s the laundromat or a friend’s house for a drink.

For me, walking is a way of getting to know a city. There’s nothing apparently productive in that act. Nothing that distinguishes me from the rest of the world, nothing that says: “this person is an artist”. No particular technique to show off, no great skill.

I try to slip into everyday life. To slip into the city and let myself be carried along by its ebb and flow. I’m not trying to produce an object. Just to be there, to experience the place and what it has to offer.

Does that mean it’s all pretence?

Can one just come along without justification? At what point does the size of a project incorporate the idea of profitability? How does this profitability influence collaborative relationships, between associate artists, between artists and organisations? I try to spot these signals. I try to be cunning. Like someone trying to get off a well-trodden road.

Peppe Frisino

“Are we meeting tomorrow in the morning? I’ll be in the old town at 8.30am and I could take you with me to some meetings. We can meet at Falanto, the bar on Via Duomo! They’re my friends, but they’re not always nice…”

Peppe Frisino is an urban planner. He’s the only member of the collective still living in the city. He lives with his family in the old town of Taranto.

It’s nine o’clock and he’s taking me to a friend’s house, a man with a shaved head in a tracksuit. Peppe introduces me as his partner. I’ve only known him for five minutes.

We go upstairs to a flat with white tiles on the floor and walls. The sofa is white, the table is light wood. Apart from that, there’s nothing in this living room.

The man explains to Peppe that he has to help him assemble a wooden frame. A huge frame measuring one metre by sixty centimetres, to which will be stapled a photo of his son, taken on the day of his communion.

Peppe, I’ll understand later, has a special role in this neighbourhood.

The old town of Taranto is built on a small island. It’s known as the historic centre because, despite its current appearance, it was and remains one of the city’s most important centres.

Everyone in the neighbourhood knows Peppe. This is his playground. He tells me that he spends 90% of his time there, while others never set foot there. Too dirty. Too run-down. Too dangerous.

Peppe walks fast. He has a cargo bike to pick up his children from school, off the island. Like you shouldn’t get away for too long.

As he crosses Via Duomo, in the heart of the island, Peppe takes his time. People stop him, he asks for news, cracks jokes, introduces me, they smile at me and speak to me in Italian.

I wonder what exactly he does for a living. What defines him. It’s impossible to understand what it means to him to be an urban planner, but I have a feeling that his approach is deeply linked to the way he relates to this place. To every person who fills the streets.

“Wednesday. Peppe is something of a trickster. Elusive, he crosses the old town of Taranto with disconcerting ease. He’s an urban planner, of course, but that title isn’t enough. He’s a neighbour, an accomplice. I’ve just arrived, and he introduces me as one of his own, blurring identities and roles. He navigates between residents, slipping from one conversation to the next, going here and there. For him, relationships take precedence over his function. Like a trickster, he doesn’t conform to expectations. He plays, improvises, twists and turns. By helping a man assemble a frame for a communion photo or chatting on the side of Via Duomo, he shapes the place without claiming it. He’s one of those figures who exist not so much by what they do as by the way they inhabit the world.”

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

Gabriella Mastrangelo

Gabriella lives in Massafra, on the outskirts of Taranto. I will join her by bus on Friday morning so she can take me to places she hasn’t told me about. I don’t seek to know. My proposal to undertake personal walks is thus taking shape. I find it reassuring.

Gabriele Leo

Gabriele came to pick me up in the historic center, by car. He explains that he arrived early that morning from Venice, where he is developing a doctoral thesis. His thesis topic: the emergence of imaginaries stemming from environmental catastrophe. His involvement in the Post Disaster collective is at the heart of his reflection.

“Post Disaster is the name of the association. It comes from Timothy Morton, an American theorist of Dark Ecology. He develops the idea that in dominant discourses, there’s much talk about the impending catastrophe, whereas in places like Taranto, the catastrophe is already here. We live in the forthcoming catastrophe, in the Post Disaster.”

Gabriele wants to take me to Mottola, a town on the outskirts of Taranto where he partially grew up. He says he’s not attached to Taranto, not like Peppe. He says he has a more complex relationship with this city, one of attraction-repulsion. “I didn’t choose to live here. I’ve rarely chosen my places of residence. Today, in Venice, I feel good.”

In Mottola, we climb one of the main streets, deserted, and arrive at a viewpoint offering one of the highest views in the region. In front of us, a few dozen kilometers away, Ilva and other factories.

Today, the pollution cloud above the factories isn’t very discernible. It varies greatly, depending on weather conditions.

People don’t come here. They don’t look at Taranto. They look at Bari. They look at Lecce. Taranto, they turn their backs on it.

“There are cities that become the reflection of a country, of its transformations, of its unresolved knots, of its failures, of its falls, but also of its aspirations for redemption. Taranto is one of those cities: a unique urban laboratory, caught between the chimneys of Ilva and the sea stretching out before its palaces, emblematic of 20th-century industrial development and its drift into a deep crisis.

Taranto is a city of layers. A city where historical, temporal, and sociological plans intertwine, often obscuring each other. Its past as the capital of Magna Graecia, a Mediterranean port traversed by cultural intermingling and foreign dominations, is just one of those layers. It’s a layer increasingly difficult to grasp, engulfed in the meanders of History and often brought to the surface in the form of dreams or hidden impulses. But the city we know today, stretching like a grayish concrete tongue over several kilometers at the top of the gulf bearing its name, is fundamentally a creation of the 20th century, marked by large industry and the development policies that shaped it.

Towards the end of the 19th century, just after Italian unification, Taranto had just over thirty thousand inhabitants, residing mainly on the ancient island constituting the old city. The construction of the military Arsenal marked the beginning of chaotic economic and urban development that would characterize Taranto throughout the 20th century. On the ruins of this military-industrial complex, the steelmaking dream was then built, the new state industry that made Taranto the most working-class city in the Mezzogiorno. But it was only much later that the extent of the damage left by this Promethean forge implanted on the shores of the Ionian Sea could be measured.” (Alessandro Leogrande, Fumo sulla città, Fandango Libri, 2013)

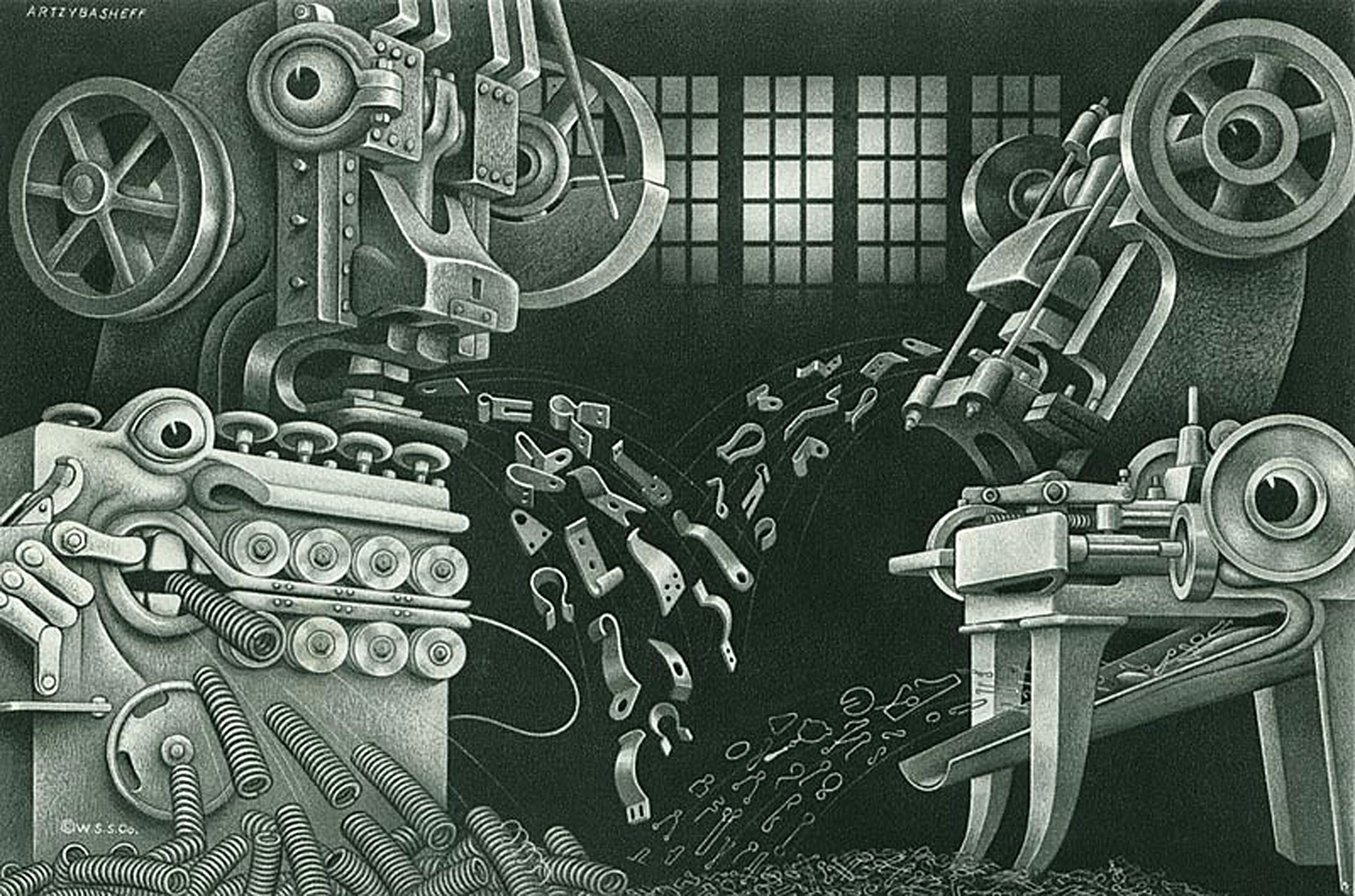

The “life” of objects

The relationship between human beings and objects, between subject and matter, is traditionally considered in terms of use, or even domination. Western philosophy, with a few exceptions, has generally made a strict distinction between the human world and the world of things, attributing to the former an absolute primacy in terms of agency and intentionality. Nevertheless, in our daily experience, this separation between us and the world of objects is much more nuanced, dynamic and interactive.

From a pragmatic point of view, one need only think of the myriad of technologies that surround us, from forks to computer networks that influence our lives. On a symbolic level, objects also play a fundamental role in the construction of individual and collective identities, actively participating in the formation of cultural, emotional and social representations. From this perspective, the strict distinction between subject and object fades away, giving way to a more complex network of mutual interactions.

In this context, American theorist Jane Bennett came up with the concept of “vibrant matter”. Matter should not be considered as passive and inert, but as infused with intrinsic vitality. Objects and matter are not reduced to simple instruments subject to human will, but exercise an agency of their own, influencing humans and actively participating in the construction of the social and political world.

According to Bennett, reality must be understood as a series of “assemblages”, where living and inert matter, animals and objects, particles, ecosystems and infrastructures all contribute equally to the production of effects. In her book Vibrant Matter, she cites and analyses the major power outage that struck the North American grid in 2003, plunging millions of people into darkness – an event that shows the extent to which an entity that is supposedly devoid of agency can exert a decisive influence on humans. As she writes: “To the vital materialist, the electrical grid is better understood as a volatile mix of coal, sweat, electromagnetic fields, computer programmes, electron streams, profit motives, beat, lifestyles, nuclear fuel, plastic, fantasies of mastery, static, legislation, water, economic theory, wire, and wood – to name just some of the actants.” By analysing the chain of events that led to this blackout, Bennett highlights its emergent character, which calls into question traditional concepts of responsibility and causality, as well as the distinction between subject and object. While such an approach is obviously manifested in a large-scale event, it can be extended to our entire experience of the world.

Moreover, on a scientific level, the traditional distinctions between living and non-living matter, organic and inorganic, are tending to blur. Materials considered to be inert are proving capable of growth, self-organisation, learning and adaptation to the environment. The idea that intelligence is an exclusively human trait is now obsolete and misleading: this is the premise on which Parallel Minds by chemist and theorist Laura Tripaldi is based. In this book, she focuses in particular on the concept of interface, which we often associate with digital technologies, but which, in chemistry, refers to a three-dimensional space with mass and thickness, where two distinct substances come into contact. In this space of interaction, materials adopt unique behaviours: Tripaldi takes the example of water, which, on contact with a smooth surface, takes the form of a drop.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

More than a technical notion, the interface invites us to rethink our relationship with matter: “In this sense, the interface is the product of a two-way relationship in which two bodies in reciprocal interaction merge to form a hybrid material that is different from its component parts. Even more significant is the fact that the interface is not an exception: it is not a behaviour of matter observed only under specific, rare conditions. On the contrary, in our experience of the materials around us, we only ever deal with the interface they construct with us. We only ever touch the surface of things, but it is a three-dimensional and dynamic surface, capable of penetrating both the object before us and the inside of our own bodies.”

The act of “touching” is also central to the thinking of philosopher and physicist Karen Barad. In her book On Touching – The Inhuman that Therefore I Am, Barad explains that, from the point of view of classical physics, touch is often described almost as an illusion: indeed, the electrons that make up the atoms of our hands and the objects we touch never actually meet but repel each other due to electromagnetic force. This means that any contact experience always occurs at a minimum distance, thus defying our sensory intuition.

Barad goes even further by analysing the question through quantum field theory, which introduces the possibility that matter is not something static and defined, but rather a continuous tangle of relationships and possibilities. The separation, which seems obvious to us, between one body and another fades away, because the boundaries between the “self” and the “other” are continually redefined, in a process that Barad calls intra/action and which would constitute the very essence of our reality – a reality where everything is constantly co-produced and co-determined. This principle implies that identity is not something pre-established but the result of infinite variations and transformations, according to a queer and non-binary model.

These approaches invite us to rethink our relationship with everyday objects and with matter in general. If matter has an agency of its own, we must recognise our belonging to a complex and interconnected system, with philosophical, political and ecological implications. Accepting that matter shapes us as much as we shape it, implies increased responsibility for our technological and environmental impact and, ultimately, for ourselves, as we inhabit assemblages, interfaces and intra/actions.

Emergency and Cocreation

Antonella Vitale is an architect who has spent part of her career designing refugee camps. Today, talking about displaced people and temporary spaces is not only a way of addressing humanitarian crises, it also implies a broader reflection about what it means to live and cohabit in a world marked by instability and climate change. The experience gained in these contexts shows that it is possible to meet basic housing needs even with limited resources, by directly involving communities and experimenting with more flexible and appropriate solutions. In refugee camps, co-creation and adaptation strategies emerge that can inspire a more general approach to architectural design. At a time of ecological emergency and forced migration, understanding how to ensure dignified living conditions in precarious situations means questioning the vulnerabilities of our own cities and rethinking the ways in which communities can be involved in the construction of living spaces.

What is the link between ecological emergency and migration?

Environmental problems, such as the scarcity of natural resources, desertification, and ecological disasters, are often closely linked to conflict and migration. The construction of refugee camps also brings its own challenges. For example, a side effect of their presence is deforestation, as displaced people need wood for cooking and, in some cases, their settlements expand. It’s important to remember that these people often live in tents for years and build temporary structures of their own accord.

How long are we talking about?

The average time spent in a camp is 17 years. That’s why humanitarian culture has evolved over time: in the past, we simply provided food, water, and temporary accommodation. Today, the aim is to offer as normal a life as possible. Rather than providing temporary accommodation, the idea is to house displaced people with local residents or in reallocated structures, if the local authorities allow it. Refugee camps do not facilitate integration because they create ghettos; they are now seen as a last resort.

What type of facilities are generally available to these populations?

Tents and containers are among the most expensive options in non-European contexts, if only for transport. Tents, in particular, are very precarious and uncomfortable, and depending on the climate, might only last six months. In addition, camps are often set up on land that hasn’t been built on, and there’s usually a good reason why: it could be prone to flooding, too hot, or impossible to cultivate. In general, it remains crucial to move as quickly as possible from the emergency response phase to a transitional phase, and then on to greater stability.

Have you had any experiences of this kind in your work?

During my assignment in Mozambique, I was involved in extending a refugee camp to accommodate an additional 5,000 people. I took over the project after the departure of my predecessor, who had encountered a number of management difficulties. One of the main problems was the fires lit by the camp residents in protest. When I arrived, the situation was complex, and the safety rules were very strict: I had to respect a time limit in the camp and return to my base before sunset. It was one of my first experiences, and I found myself faced with a major challenge, with no clear guidelines on how to proceed, and few resources.

What approach did you take?

I chose to maximise my time in the camp by starting to interact with the different communities. The camp was home to groups from the Great Lakes region of Africa, people marked by deep-rooted tribal conflict. I tried to understand their situation and involve them in the decision-making process, giving them the task of pointing out problems and essential needs. If I hadn’t done this, there would probably have been opposition, because unwittingly, for example, we would have exacerbated enmities between clans by intervening in stories we couldn’t understand, and fuelling tensions.

What strategies did you use to involve the camp residents?

The key moment was the launch of the design and planning phase. I let the residents tell me their needs, aspirations, and preferences for the layout of the homes. For me, the most important thing was to respect the number of people to be housed, while the distribution of the spaces was up to them. This approach had a very positive impact on the feasibility of the project. My constant presence in the camp also helped to deconstruct the prejudice that international aid workers are distant, locked away in their air-conditioned offices or jeeps. By showing that I was willing to listen, I fostered a climate of trust.

How did you overcome the language barrier?

To facilitate communication and mutual understanding, I chose to display the project drawings in visible places in the camp. This aroused the curiosity of the residents, who approached me for information in order to take an active part in meetings. Thanks to this method, we were able to better define the distribution of living spaces according to the real needs of the community. In the end, the key element of this experience was not the technical aspect, but the ability to listen and respond to people’s needs, initiating a process of co-creation that made the project more effective.

Drawing: © Anaëlle Clot.

How did you intervene in public spaces?

The camp included empty areas that served as natural gathering points, such as those around the water pumps, often located under large trees. One of these points was close to the therapeutic feeding centre for children under five and not far from the school. I analysed these existing synergies and integrated them into the creation of a sports field, strategically positioned to encourage physical activity and movement.

In addition, in this area I introduced a more structured communication system, using a tree as a display point for comments, suggestions, and complaints from the community. Although there was more criticism than praise, this system established a clear and direct channel of communication. My aim was to facilitate discussions between the operators and the community, gathering useful feedback to improve the management of the camp. When there’s participation, co-creation or at least an exchange of ideas, people are willing to get involved, especially if it has to do with buildings or the use of space.

How much freedom was there for self-designing buildings?

In Mozambique, we involved people in the construction of houses using local materials: reeds, earth, and straw. Each family was provided with the same quantity of materials, and they could then decide how to use them by appropriating the project. The idea was to move on from tents to very simple but permanent houses, in line with Mozambican standards. It’s also important to bear this in mind: when offering an emergency solution to a population from outside the country, you mustn’t go beyond what the most disadvantaged members of local society have, so as not to fuel tensions.

Are there other levels of co-creation that are desirable in such a context?

Before leaving their country of origin, displaced people had a trade, occupations, and passions. Mapping these skills is an asset that can be exploited to the full, firstly to integrate these people into the world of work and make them self-sufficient, and secondly to contribute to aid programmes for displaced people. Since resources are limited, taking advantage of local skills is a great opportunity. It’s not always easy, it takes time, and you have to meet people, but it’s of enormous benefit to the community, which feels respected rather than marginalised.

Are there any spontaneous practices in the public space that help to foster cohesion?

Food is an important tool of cultural identity, especially in contexts of great disorientation. The opportunity to grow traditional foods not only provides a means of subsistence but also enables people to maintain a link with their culture of origin and share it with the local population. This practice creates opportunities for cultural exchange, for example through small food outlets where camp residents can share their cuisine. It can also facilitate the exchange of agricultural or culinary techniques useful to both the refugee and host communities.

What is the relationship between emergency and planning?

Emergency and planning are almost antagonistic, because in an emergency situation, by definition, there is no time or opportunity to plan. However, we mustn’t fall into the trap of continuous emergency either, as that would be naïve, costly, and politically dangerous. In an emergency, many rules have to be waived. Legislation requires time, strict processes, and co-creation, but it is also the only way forward.

What can we learn from housing in emergency contexts?

In emergency contexts, we learn that delaying action progressively reduces the options available, until none are left. Today’s multiple crises, including climate change, teach us that it is essential to act in time, even in Europe, where, despite resources, cities are not ready to face current and future environmental challenges.

In some parts of the world, climate crisis is gradually rendering entire regions uninhabitable. The problem is not just rising temperatures, but the disappearance of vital resources, forcing people to migrate. However, global attention is more often focused on protecting against migratory flows than on long-term interventions to prevent crises.

Living Soil

Although we walk on it every day and it is essential to our food security, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives. What crucial roles does soil play in maintaining the balance of ecosystems? How can we protect it? And how can artistic practices help?

Below is an interview with Karine Gondret, a trained soil scientist and geomatician, HES-SO research associate and lecturer at the Geneva School of Landscape, Engineering and Architecture (HEPIA). Her research focuses on soil quality assessment and mapping.

What is pedology?

A branch of soil science, pedology focuses on the study of soils, i.e. the interactions between living organisms, minerals, water, and air that take place beneath our feet. In pedology, we examine everything that lies between the surface and the first, purely mineral layer, i.e. around 1.50 m deep in our latitudes. Beyond that, when only minerals remain, we enter the field of geology. The role of the pedologist is also to map the soil.

What is meant by good quality soil?

Broadly speaking, good quality soil is soil that is capable of performing the functions necessary for the survival of all living organisms and their environment. Several functions are very important, beyond the most obvious, that of food or biomass production. Soil infiltrates, purifies, and stores water, and recycles nutrients and organic matter. There is also the genetic reserve function, which is still seldom studied. Penicillin, for example, was discovered in the soil. So it’s crucial to protect our soils.

What parameters need to be taken into account to assess the quality of a soil according to its functions?

In general, the higher the organic content of soil, the better it is able to perform its functions. By organic, we mean all living things (earthworms, micro-organisms, bacteria, etc.) and all carbon-rich compounds derived from living things (corpses, excrement, roots, dead leaves, compost, root and bacterial exudates, etc.). Functioning soil is living soil, and much more!

There are several other essential parameters, such as soil depth, pH, texture, porosity, etc. Depending on the function, certain parameters will be more or less important. For example, the function of supporting human infrastructure (roads, buildings, etc.) will inevitably be detrimental to the biomass production function. That’s why politicians have to make choices about the functions they want to protect.

Why is the presence of organic matter in soils important?

Organic matter is the basic food source for the soil’s fauna and micro-organisms. It is continually broken down by soil life into nutrients that are accessible to plants via soil water. Organic matter also improves soil porosity. Porosity is essential for the proper development of life, as it allows nutrient-rich water, air, and roots to circulate. Without this porosity, exchanges are much less effective, and as a result, its functions are much less effective.

In addition, organic matter is capable of increasing the soil’s capacity to store water and of mitigating flooding in towns downstream. It can also retain nutrients and pollutants through its electrical properties. Finally, organic matter that is stabilised in the soil contains around 60% of carbon, and the more it increases in the soil, the more we limit global warming, because all the carbon that is not stored in the soil goes into the atmosphere in the form of CO2.

We’ve talked about what good soil is for humans, but what about the “more than human” world?

As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), soil performs functions that are essential to humankind. In truth, these functions are essential to the proper functioning of ecosystems, and humans simply benefit from them. For example, many pollinators spend part of their life cycle in the soil. These pollinators make it possible to obtain fruit and feed wildlife, which is beneficial for natural environments. But this fruit also benefits humans within agricultural and economic infrastructures, when it is sold. Humans and the environment are deeply interconnected, although we tend to forget this. Finally, compared to about fifty years ago, the organic matter content in most agricultural soils has halved. This means that these soils are becoming increasingly less effective at performing the functions they provide for us.

Images: Thierry Boutonnier, Comm’un sol, 2024. Photo: ©Eva Habasque.

As part of the Faire Commun research project, artist Thierry Boutonnier devised a method for sensitively assessing the quality of the soil in Parc Rigot. He organised a picnic on a long organic cotton tablecloth, which was then cut into pieces and buried in different areas of the park. After a few months, the tablecloth was dug up, and the amount of fabric consumed thanks to the soil’s bioactivity provided concrete information about its characteristics. What did you observe?

We haven’t yet finished carrying out the analyses in Parc Rigot, but we’ve observed the soil’s capacity to degrade organic matter through this experiment. In the soil, micro-organisms release enzymes that degrade organic matter (here the cotton tablecloth). We also observed that these micro-organisms were not all equally active: in some areas of the park, the organic matter was broken down very efficiently, while in other areas, the process was much slower. This means that in these areas, there are fewer nutrients available for the plants that grow.

People often don’t realise that there is diversity of soils, even in small areas. In the city, as in Parc Rigot, this diversity is even more marked because humans have had such a strong impact on the soil. There have been many interventions – areas have been completely renatured, others stripped, or artificially added – and this has led to a juxtaposition of very different soils. The challenge is to identify the areas that really work, and protect them.

Is it possible to improve soil quality?

When soil doesn’t have the necessary quality for a given function, we can intervene to improve it, for example by adding organic matter or by decompacting it (in compliance with the OSol ordinance in Switzerland). Nevertheless, soil quality only improves very slowly; sometimes it takes several human generations, sometimes improvement is impossible. Soil is a non-renewable resource, as it takes a very long time to create: it is said to increase by an average of 0.05 millimetres per year. In very steep areas, it even becomes thinner and thinner.

It can also deteriorate rapidly. It looks solid and is thought to be immutable, but nothing could be further from the truth. Even when we’re trying to improve its quality, we have to be very careful, because every intervention on the soil leads to its deterioration. It’s a delicate process that doesn’t always work – we’re still experimenting.

Soil is at the intersection of physics, biology, and chemistry. It’s a complex world, and by no means do we know everything about it. So it’s all the more important to protect it, because it’s where all plant nutrients are found, and as they develop, they form the basis of the diet of all mammals. The soil is truly the place where life is created.

Fences and Power

“We pray your grace that no lord of no manor shall common upon the common.

We pray that all freeholders and copyholders may take the profits of all commons, and there to common, and the lords not to common nor take profits of the same.

We pray that Rivers may be free and common to all men for fishing and passage.

We pray that it be not lawful to the lords of any manor to purchase lands freely, (i.e. that are freehold), and to let them out again by copy or court roll to their great advancement, and to the undoing of your poor subjects.”

The date is 6 July 1549. The peasants of Wymondham, a small town in Norfolk, England, have risen in rebellion. They are marching across the fields to cut down the hedges and fences of private farms and pastures, including the estate of Robert Kett, who surprisingly joins the protests, giving his name to the rebellion. As they march, they are joined by farm workers and craftspeople from many other towns and villages. On 12 July, 16,000 insurgents camp at Mousehold Heath, near Norwich, and draw up a list of demands addressed to the King, including those mentioned above. They will hold out until the end of August, when more than 3,500 insurgents will be massacred and their leaders tortured and beheaded. But what provoked this insurrection? And why was the repression so bloody?

Kett’s Rebellion was a reaction to the hardships inflicted by the extensive enclosures of common lands. These lands, which were of great economic and social importance, were managed according to rules and boundaries established by the communities themselves, guaranteeing a balance between their members. The plots were used for grazing, gathering wood and wild plants, haymaking, fishing, or simple passage, and even included shared farmland, where peasants each cultivated small portions of the collective land. The common land system thus contributed to the subsistence of the communities and, in particular, the most disadvantaged.

With enclosures, common land was reorganised to create large, unified fields, demarcated by hedges, walls, or enclosures, and reserved for the exclusive use of large landowners or their tenants. This gradual process of land appropriation was not exclusive to England but was a large-scale phenomenon that spread in various forms throughout Europe (and even more violently in its colonies) from the 15th century onwards. This is the phenomenon that Karl Marx describes in Das Capital as “primitive accumulation”: agricultural workers, deprived of their means of production (land), are forced to work for wages, possessing nothing other than their labour power. This was one of the factors that led to the emergence of capitalism, a process involving violence, expropriation, and the breaking of traditional social ties.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

Another significant aspect of enclosures is their impact on the role of women. Until the Middle Ages, a subsistence economy prevailed in Europe, in which productive work (such as tilling the fields) and reproductive work (such as caring for the family) had equal value. With the transition to a market economy, only work that produced goods was considered worthy of remuneration, while the reproduction of labour power was deemed to have no economic value. What’s more, as we have shown, the loss of use rights over common land particularly affected already-discriminated groups such as women, who found in this land not only a means of subsistence, but also a space for relationships, knowledge sharing, and collective practices.

Feminist researcher Silvia Federici, in her celebrated book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, reflects on the link between the privatisation of land and the worsening of women’s condition: “For in pre-capitalist Europe, women’s subordination to men had been tempered by the fact that they had access to the commons and other communal assets (…). But in the new organisation of work every woman (…) became a communal good, for once women’s activities were defined as non-work, women’s labour began to appear as a natural resource, available to all, no less than the air we breathe or the water we drink (…). According to this new social-sexual contract, proletarian women became for male workers the substitute for the land lost to the enclosures, their most basic means of reproduction, and a communal good anyone could appropriate and use at will.”

The consequences of this exacerbation of power relations between the sexes were manifold: women found themselves increasingly confined to the domestic sphere, economically and socially dependent on male authority, and controlled in the management of their bodies by demographic policies that were essential to a society dependent on the flow of labour power. Control of the female body, through the condemnation of contraception and the traditional knowledge associated with care, became central to the emerging capitalist society. The witch-hunts that struck down thousands of women in Europe and America were part of this repression and control.

In the European colonies, similar processes of expropriation and violence were justified by the rhetoric of domination over “savages”. This pattern, based on the extraction of resources and cheap labour, continues to this day: think of the appropriation of indigenous lands in the global South for the exploitation of natural resources. Capitalism and oppression are two sides of the same coin.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality, wrote: “The first person who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of society. From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows, ‘Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’”

Rousseau’s thinking in this book is not without its problems, and, among other things, fuelled the dangerous myth of the “good savage”, which would in part justify colonialism. Yet these words represent a warning and a hope, inviting us to question the very foundations of society: structures, institutions, and economic systems are not immutable. Change is always possible, provided we have the courage to imagine it.

Autumn in the Garden

The gardener, hands immersed in the soil and in constant contact with plants, might seem to have an idyllic job in the face of urban hassles. But, according to Karel Čapek, nothing could be further from the truth. In his book The Gardener’s Year (1929), Čapek describes the gardener’s problems and tribulations in the face of frost, drought, and the overweening ambitions of small urban gardens. His wonderfully written tale, imbued with irony, offers a reflection on the complexity of human nature, not without a touch of humour and levity. Below is a short extract from the book.

We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn. While we only look at nature it is fairly true to say that autumn is the end of the year; but still more true it is that autumn is the beginning of the year. It is a popular opinion that in autumn leaves fall off, and I really cannot deny it; I assert only that in a certain deeper sense autumn is the time when in fact the leaves bud. Leaves wither because winter begins; but they also wither because spring is already beginning, because new buds are being made, as tiny as percussion caps out of which the spring will crack. It is an optical illusion that trees and bushes are naked in autumn; they are, in fact, sprinkled over with everything that will unpack and unroll in spring. It is only an optical illusion that my flowers die in autumn-; for in reality they are born. We say that nature rests, yet she is working like mad. She has only shut up shop and pulled the shutters down; but behind them she is unpacking new goods, and the shelves are becoming so full that they bend under the load. This is the real spring; what is not done now will not be done in April. The future is not in front of us, for it is here already in the shape of a germ; already it is with us; and what is not with us will not be even in the future. We don’t see germs because they are under the earth; we don’t know the future because it is within us. Sometimes we seem to smell of decay, encumbered by the faded remains of the past; but if only we could see how many fat and white shoots are pushing forward in the old tilled soil, which is called the present day; how many seeds germinate in secret; how many old plants draw themselves together and concentrate into a living bud, which one day will burst into flowering life—if we could only see that secret swarming of the future within us, we should say that our melancholy and distrust is silly and absurd, and that the best thing of all is to be a living man—that is, a man who grows.

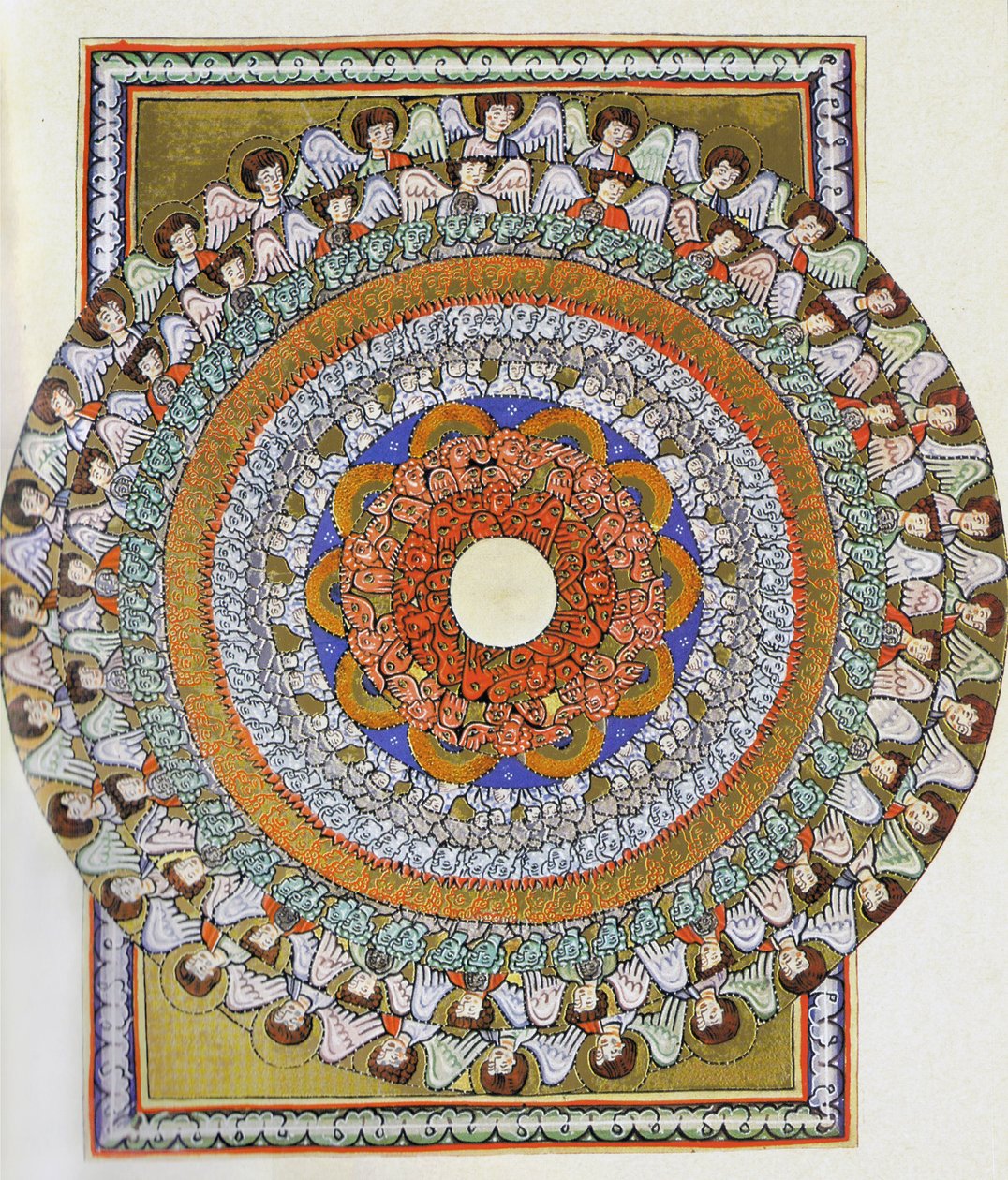

Image: Natália Trejbalová, Few Thoughts on Floating Spores (detail), 2023.

Courtesy of the artist and Šopa Gallery, Košice. Photo: Tibor Czitó.

How happy is the little stone

In this brief poetic composition, Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life, represented by a small stone wandering freely. Far from human worries and ambitions, the stone finds contentment in its elemental existence. Written in the 19th century, the poem reflects the growing disillusionment with industrialisation and urbanisation, which led many to aspire to a more modest and meaningful life.

How happy is the little stone

That rambles in the road alone,

And doesn’t care about careers,

And exigencies never fears;

Whose coat of elemental brown

A passing universe put on;

And independent as the sun,

Associates or glows alone,

Fulfilling absolute decree

In casual simplicity

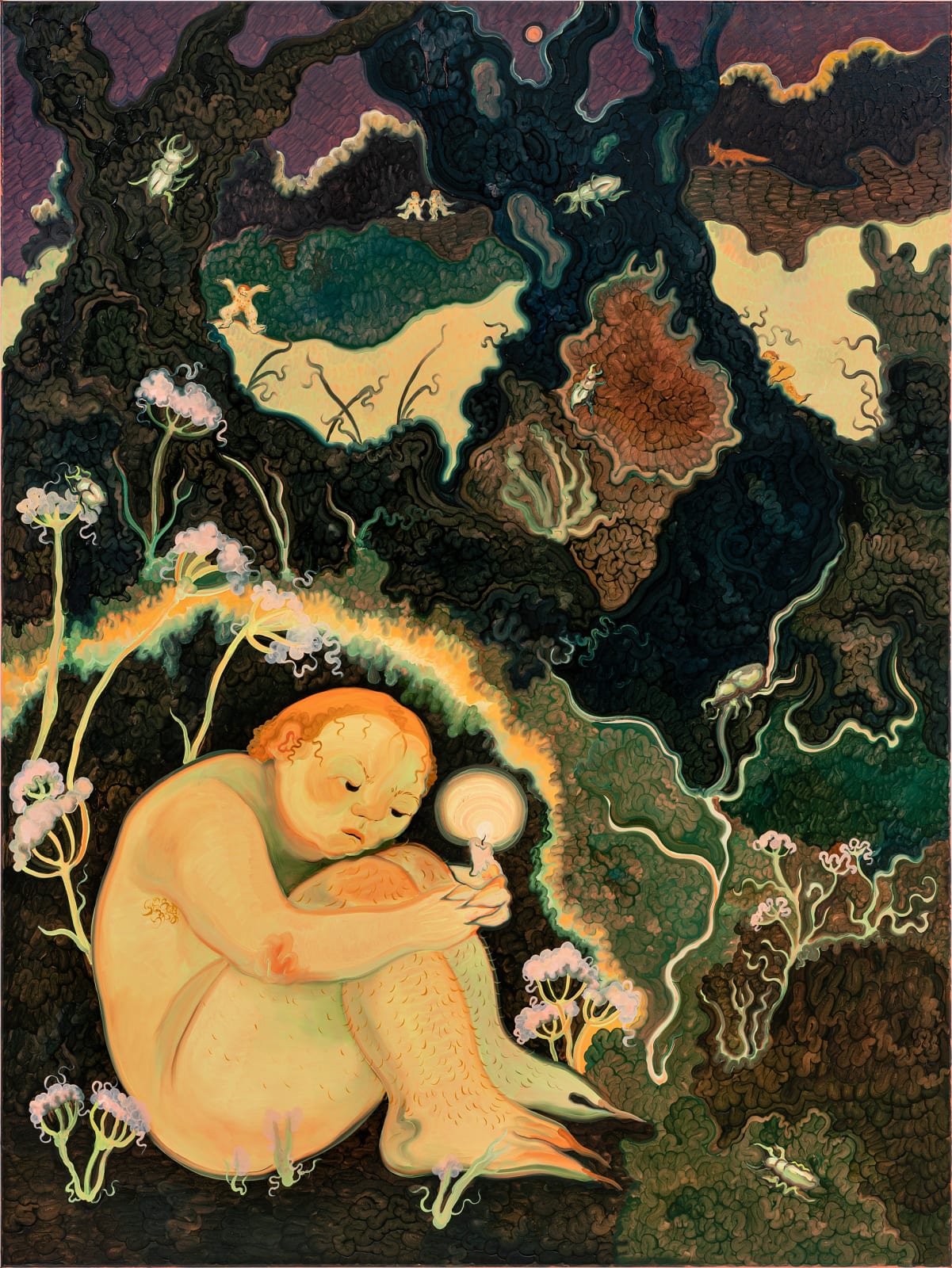

Image: Altalena.

Ô noble Green

O noble Green, rooted in the sun

and shining in clear serenity,

in the round of a rotating wheel

which cannot contain all the earth’s magnificence,

you Green, you are wrapped in love,

embraced by the power of celestial secrets.

You blush like the light of dawn

you burn like the embers of the sun,

O most noble Viriditas.