laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

Vivre le Rhône

Created by Natural Contract Lab together with least, Vivre le Rhône featured an ongoing artistic practice from 2022 to early 2024, led by Maria Lucia Cruz Correia, that advocates a form of ecology of repair based on dialogue with bodies of water undergoing profound ecological transformation.

Following an initial phase of research, a number of local communities, featuring activists, students and water management professionals, were invited to participate in a series of walks along the river. The walks were initiated by Natural Contract Lab’s artistic team through rituals which were designed to recognise the ecological damage inflicted upon the River Rhône and each person’s relationship with the water.

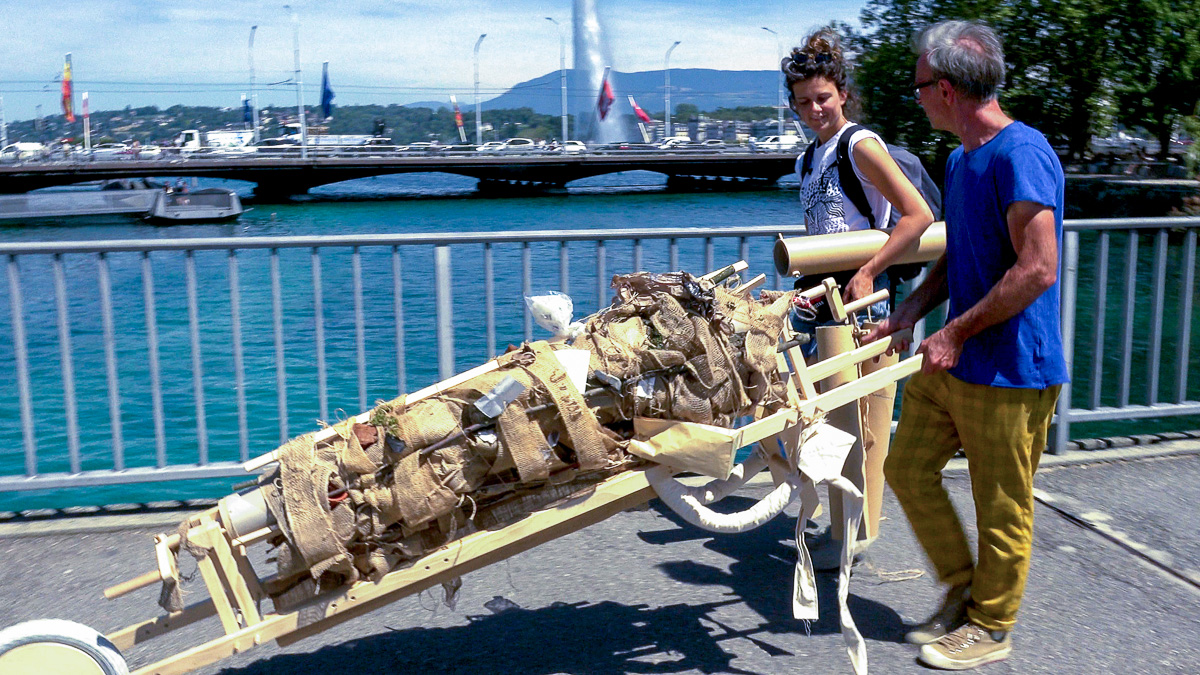

Using collecting tools, the participants gathered leaves, moss, plastic bottles, pieces of wood, waste paper and shells, i.e. objects that triggered memories, stories and reflections, which were then stitched together to form a legal/sensory cartography, i.e. a device to represent not only the physical geography of the river, but also the community’s relationship with it, the different living species and the wounds suffered by the ecosystem.

The actions and devices of Vivre le Rhône aimed to use artistic practice to foster new ideas and laws for the governance of ecosystems and to expand a network of River Guardians.

research & process

We devoted the first phase of the project to interdisciplinary research on the River Rhône, with the aim of reconstructing its history and acknowledging the ecological damage it has suffered. The research involved a series of explorations and meetings with people linked in various ways to the river in Switzerland, i.e. water management professionals, historians, geographers, fishermen, social workers, activists and citizens. The long-term process that began with the research has generated published works as well as the creation of videos and podcasts by young artists Maud Abbé-Decarroux, Audrey Bersier, Martin Reinartz and Carlos Tapia.

walking, gathering, weaving

Throughout 2022 and 2023, we pursued a series of collective practices of walking with the river. When we first encountered the Rhône, we sought to greet and collect its water in a vessel created by ceramic and visual artist Zahra Hakim, which we carried as a mediator between us and the river. During our walks along the banks of the river, we collected objects and stories linked to it and wove them together. A number of tools and a “river loom” designed by architects and designers Maud Abbé-Decarroux and Lode Vranken were used to collect the objects and weave them together and to form a temporary community for each walk. Today, these “weaving subjects” remain with the River Guardians, while the river loom has been donated to a school.

a sensorial-juridical cartography

In 2023, we worked with lawyer Marine Calmet and talked with OCEau (Cantonal Office of Water) to imagine how to include, in a written law on river rights, what is usually overlooked, i.e. the relationship between peoples and the river, their love, their sorrow, their memories and the care they show for it in the face of eco-landscape disappearance. The things that were gathered and woven together during the walks – whether a piece of moss, a bird song, a reflection of light on the river or a trace of rubbish – served as the starting point for the project and today as tools to support discussions for a future law. A publication, illustrated by Maud Abbé-Decarroux and directed by least, recounts the thought process behind it.

a community of river guardians

Last July, over three days, we organised a series of events to reflect on the expansion of a legitimate community to act on behalf of the River Rhône. A “River Agora” was organised in Porteous, where we listened to the stories of Rhône guardians from different parts of the river (Rhône glacier, Valais, Geneva, river mouth in France) and wove together new forms of collective actions as water carriers. We then gathered at Île Rousseau to open our legal/sensory cartography and bind our threads together. There, we invited everyone to reweave the storyline and memories of the river and to create new patterns and a living statement for the Rhône. Finally, we unravelled our legal/sensory cartography and made offerings to the river. These public events helped launch a network of people and organisations – such as Appel du Rhône and other associations involved in nature conservation – interested in the guardianship of the Rhône and in pursuing collective action to have it recognised as a legal subject.

newsletter

All participatory actions, locations and walks were communicated on our website and via least’s newsletter.

artistic team

NCL founded in 2021 by the artist Maria Lucia Cruz Correia in collaboration with a multidisciplinary group:

Marine Calmet - rights of nature

Brunilda Pali - restorative justice

Lode Vranken - design / philosophy

Vinny Jones - sensorial scenography

Evanne Nowak - ecological grief

Margarida Mendes - research / sonic guidance joined the collective in 2022

Équipe locale

Maud Abbé-Decarroux - cartography / design

Audrey Bersier - podcast / sound

Martin Reinartz - artist-in-residence at least

Carlo Tapia - video

least would like to thank all the people that contributed to the project by sharing their time, knowledge and resources:

Appel du Rhône; Tony Arborino (engineer and consultant on water and sustainability) / EPFL - École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne; Philippe Benetti and Gaëlle Cervantes / Centre de compétences pour déficits visuels; Mathilde Captyn / Association éco-impact; Armelle Choplin (geographer) / University of Geneva; Laure Delory (activist) / Swiss Association for Climate Protection; Alain Dubois and Pierre-François Mettan / Association Fêtes du Rhône; Floriane Facchini (artist / director); Luca Ferrero (fisherman); Sylvie Fischer / Association F-information; Sophie Frezza; Stéphane Genoud (energy management engineer) / HES-SO Valais-Wallis; Zhara Hakim (artist / ceramist); Kimberly Hirsch; Felix Küchler (doctor, climate activist); Le Grand Atelier; Anne Mahrer / Aînées pour la protection du climat; Gilles Mulhauser / Canton de Genève - Office cantonal de l’eau; Frédéric Pitaval (engineer) / Emma-Louise Lavigne / Association id-eau; MACO la Manufacture Collaborative; La Manivelle; Laurence Piaget-Dubuis (eco-artist, graphic designer, photographer) / Watergaw; Michel Porret (historian) / University of Geneva; Association Porteous; Emmanuel Reynard (geographer) / Association mémoire du Rhône; Philippe Savary (fisheries warden) / Association des gardes-pêches de Suisse romande; Marie-Thérèse Sangra (geographer and chargé d’affaires) / WWF Valais; Mara Tignino (water rights, researcher) / Geneva Water Hub - University of Geneva; City of Vernier.

media

Everything Flows

Reading

Life relies on a delicate synchronization between the rhythms of living beings and the cycles of the Earth.

Faire commun

Vivre le Rhône

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Experiencing the Landscape

Reading

The complexity of the term ‘landscape’ can best be understood through the concept of ‘experience’.

Vivre le Rhône

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Vivre le Rhône: part 3

Video

River Guardians

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 03

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 02

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: part 2

Video

When art meets law.

Vivre le Rhône

Guardians of Nature

Reading

An interview to Marine Calmet, lawyer specialised in environmental law and Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Vivre le Rhône

Bodies of Water

Reading

Embracing hydrofeminism.

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 01

Audio

An audio project tracing the experiences of those who have come closer to the river by walking.

Vivre le Rhône

Putting Off the Catastrophe

Reading

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously?

Common Dreams

Vivre le Rhône

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

A urge to do something

Reading

An interview to climate activist Myriam Roth.

Vivre le Rhône

Vivre le Rhône: part 1

Video

Meet the Rhône and Natural Contract Lab

Vivre le Rhône

Everything Flows

As part of Faire commun – a shared ecology project in Parc Rigot – least invites you to reflect on the rhythms that flow through living beings, places and time itself. “Faire commun” also means “making time together”: exploring how our lives align – or fall out of step – with the cycles that surround us. This text invites readers to attune to the world’s many pulses, imagining new forms of sensitive coexistence.

At Parc Rigot, students, researchers and artists came together to resonate with the land – an interdisciplinary and sensory exploration aimed at revealing the unique rhythms of the landscape, its lifeforms and its uses. By observing the park’s centuries-old oaks, its passers-by and its pond, they highlighted how each element vibrates at its own tempo – sometimes steady, sometimes chaotic – composing a shared, living score.

The word “rhythm” comes from the Greek verb rhéô, meaning “to flow”. In Greek philosophy, panta rhei (“everything flows”) captures the thought of Heraclitus of Ephesus, philosopher of perpetual change: all is in constant transformation, like a river whose waters move constantly, so much so that “one can never step into the same water twice” …

Water, indeed, is at the heart of our first experience of rhythm. Even before birth, we perceive sound through amniotic fluid: heartbeats, breath, blood flow. Only low, rhythmic sounds travel through this liquid medium. After birth, part of this water remains in us: the inner ear, still filled with fluid, senses the world’s vibrations. This original water holds a deep memory of rhythm and time within us. Perhaps that is why Rigot’s pond, nestled at the base of the park, acts as a sensory magnet: it draws the eye, attracts wildlife and becomes a focal point where human and non-human rhythms converge across the day.

Humanity has long sought to measure time. One of the earliest known instruments is a water clock (clepsydra) from the 14th century BCE, discovered in the Karnak Temple in Egypt. Two vessels, connected by a small opening, allowed time’s flow to be measured steadily. At Rigot, the oaks planted on the western side play a similar role: silent timekeepers, inscribing memory into their bark year after year.

In soundscapes little touched by human activity, most sounds follow predictable rhythms. Birdsong, the rustle of wind in leaves, the soft lapping of water – these recurring motifs are registered by living beings as familiar and non-threatening. Such regularity soothes and stabilises the soul. In contrast, abrupt noises – construction, crowds, traffic – disrupt sensory balance, triggering alarm. Auditory rhythm is thus a key element of perceptual stability.

Rhythm is essential to how every species hears. Neurons in the ear and brain activate only when sound frequencies align with a reference rhythm. In the 1960s, Hungarian researcher Péter Szőke slowed down birdsong to reveal its hidden complexity, unheard by the human ear. This attention to the invisible and the subtle informs the sensory work carried out in Parc Rigot: to listen, to slow down, to observe what often slips beneath the surface of perception.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

For living beings, time unfolds on three levels: internal rhythm, synchronisation with environmental cycles and coordination with others. Internal rhythm is fine-tuned by external signals – zeitgebers (“time-givers”) – such as light, temperature and seasons. For migratory birds, the memory of thawing snow, the length of day and the behaviour of other species help determine when to depart for breeding grounds.

Time, then, is not solely personal, it is also social. In a beehive, nurse bees maintain a constant internal rhythm, while foragers adjust to the timing of flower openings. The coordination of these internal clocks generates a shared rhythm, or a collective time.

Human societies, too, maintain diverse and complex relationships with time. In many Indigenous cultures, time is tied to local rhythms of land, animals and landscapes. Among Sámi reindeer herders, for instance, the concept of jahkodat holds that each year is unique: migration depends on the snow thawing, pasture health and other shifting factors. “One year is not the sister of the next”, a Sámi proverb says: each cycle demands careful attention and constant adaptation.

Today, globalisation has dulled this seasonal sensitivity. Yet seasonality is not universal. Some regions know four seasons; others alternate between wet and dry. In Nagori, Ryoko Sekiguchi notes that Japan traditionally divides the year into 24 seasons, or even 72 micro-seasons. This refined sense of time shapes language itself, with words and haikus linked to precise moments, weaving culture, climate and expression together.

But so-called “objective” time is also a human invention. In Austerlitz, W.G. Sebald reminds us that while time is tied to the stars, it ultimately rests on convention. Even the solar day varies; to stabilise our clocks, we invented a “mean sun” – a fictional body whose steady motion serves as a reference.

The standardisation of time intensified in the 19th century with the advent of railways. To coordinate schedules, time zones were imposed, overriding the diversity of local times. The world entered an era of strict synchronisation, a standardisation that now coexists with the ecological and temporal dissonance we face.

For non-humans, life depends on a fine attunement between living rhythms and Earth’s cycles. Climate change is unsettling these balances. At Rigot, as elsewhere, seasons shift, temperatures rise, blooms and migrations fall out of sync, disrupting biological clocks. This breakdown threatens the reproduction, food sources and survival of many species. When life’s rhythms fall out of step with Earth’s cycles, the very balance of life begins to waver.

In the face of growing dissonance between human time and living time, Faire commun calls for a sensitive reorientation: to slow down, to listen, to live together. Parc Rigot becomes a shared learning ground, where we can explore new ways of inhabiting time, neither linear or productivist, but rather cyclical, porous, attuned to what grows, changes or disappears. By reconciling Earth’s many temporalities, this project sketches the outline of an inhabitable future.

Experiencing the Landscape

In everyday language, the term “landscape” encompasses a variety of notions: it can refer to an ecosystem, a beautiful view, or even an economic resource. However, the complexity of the term can be better understood and approached through the concept of “experience”.

Experience is something that brings us into contact with the outside, with otherness: in this context, the landscape is no longer seen as an object, but rather as a relationship between human society and the environment. An experience is also something that touches us emotionally, that moves and transforms us. Viewing a “landscape” as such helps us realise how much it gives meaning to our individual and collective lives, to the extent that its transformation or disappearance leads to the destruction of sensitive markers of existence in the lives of its inhabitants. Experience can also be seen as a form of practical knowledge or wisdom. It is the kind of knowledge that is acquired by living in a place, which makes the people who inhabit a landscape its experts. Finally, experience is also a form of experimentation: this is the active aspect of our relationship with the world, enabling us to discover and create new knowledge and to bring to life what is yet only potential.

We might take these reflections a step further and argue that human beings live off the landscape—a statement that may seem hyperbolic, but that makes sense if we pay close attention. Indeed, the landscape is the source of our food: we live in the landscape and the latter activates representations and emotions within us. Our relationship with the landscape is dynamic: by changing it, we also change ourselves. It is therefore impossible to avoid entering into a relationship with the landscape. The very choice of ignoring and not ‘experiencing’ a landscape can have practical and symbolic consequences.

It is on the basis of these observations that Jean-Marc Besse wrote La Nécessité du Paysage (the Necessity of the Landscape): an essay on ecology, architecture, and anthropology, as well as an invitation to question our modes of action. In it, the French philosopher warns us against any action on the landscape: an attitude that places us ‘outside’ the said landscape, which, as mentioned above, is simply not plausible. Acting on a landscape means fabricating it, in other words starting from a preconceived idea that ignores the fact that the landscape is a living system and not an inert object. “Acting on therefore involves a twofold dualism, separating subject and object on the one hand, and form and matter on the other.”

So how might we escape this productive yet falsifying paradigm? Besse suggests a change of perspective: moving from acting on to acting with, recognising “that matter is animated to a certain extent” and envisaging it “as a space of potential propositions and possible trajectories”. The aim, in this case, is to interact “adaptively and dynamically”, to practise transformation rather than production. Acting with means engaging in ongoing negotiation, remaining open to the indeterminacy of the process, and being in dialogue with the landscape: in a word, collaborating with it.

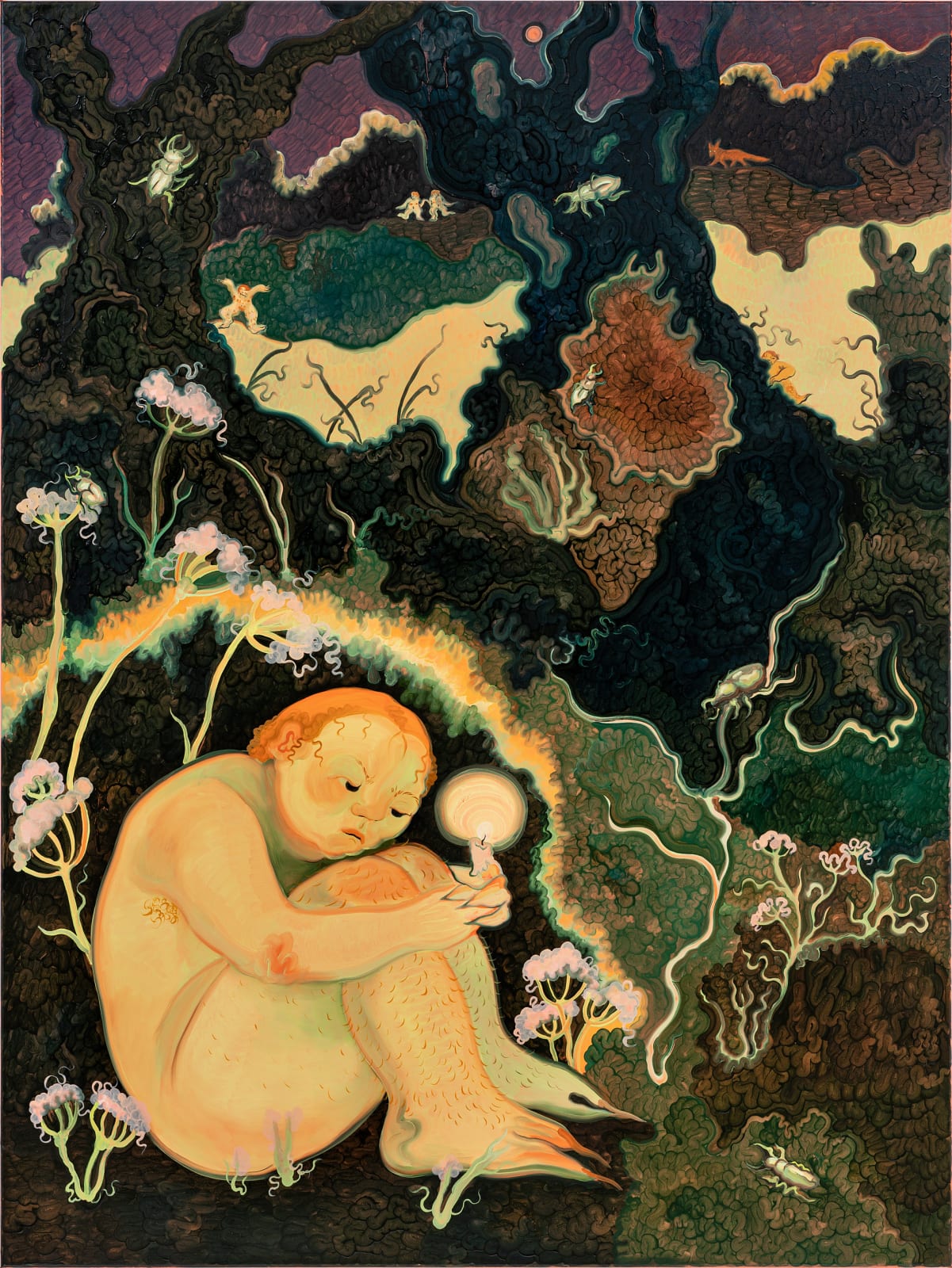

Georg Wilson, All Night Awake, 2023

Acting with the soil

The “abiotic” dimension of soil is addressed, among other disciplines, by topography, paedology, geology, and hydrography. However, from a philosophical point of view, soil is simply the material support on which we live. This is where we construct the buildings we live in and the roads we travel on, and it is the soil that makes agriculture possible, one of the oldest and most complex fundamental manifestations of human activity. This “banal” soil is therefore in reality the focus of a whole series of essential political, social, and economic issues, and as such it raises fundamental questions. What kind of soil, water, or air do we want? The environmental disasters linked to the climate crisis and soil erosion or the consequences of the loss of fertility of agricultural and forest land call for collective responses that draw on both scientific knowledge and technical skills, as well as many political and ethical aspects.

Acting with the living

The landscapes we inhabit, travel through, and transform (including the soil and subsoil) are in turn inhabited, travelled through, and transformed by other living beings, animals and plants. In his essay Sur la Piste Animale (On the Animal Trail), philosopher Baptiste Morizot invites us to live together “in the great ‘shared geopolitics’ of the landscape”, by trying to take the point of view of “wild animals, trees that communicate, living soil that works, plants that are allies in the permacultural kitchen garden, to see through our eyes and become sensitive to their habits and customs, to their immutable perspectives on the cosmos, to invent thousands of relationships with them”. To interpret a landscape correctly, it is necessary to take into account the “active power of living beings” with their spatiality and temporality, and to integrate our relationship with them.

Acting with other human beings

A landscape is a “collective situation” that also concerns inter-human relations in their various forms. A landscape is linked to desires, representations, norms, practices, stories, and expectations, and it draws on emotions and positions as diverse as people’s desires, experiences, and interests. Acting with other human beings means acting with a complex whole that includes individuals, communities, and institutions, and drawing on the practical and symbolic—in a continuous process of negotiation and mediation.

Acting with space

Considered through the tools of geometry, space is an objective entity: its dimensions, proportions, and boundaries can be satisfactorily described. However, the space of the landscape cannot be reduced to measurable criteria. In reality, it is an intrinsically heterogeneous space: “locations, directions, distances, morphologies, ways of practising them and of investing in them economically and emotionally are not equivalent either spatially or qualitatively”. Interpreting the space of the landscape correctly therefore means remembering that “numerical” and “geometric” measurements are necessarily false, and that the set of geographies (economic, social, cultural, or personal) that make it up are neither neutral, nor uniform, nor fixed in time.

Acting with time

When we think of the relationship between landscape and time, the first image that springs to mind is that of the earth’s crust and the geological layers that make it up, or that of archaeological ruins buried beneath the surface. In short, we imagine a sort of tidy “palimpsest” of a past time, with which all relations are closed. The time of the landscape, however, should be interpreted according to more complex logics: we need only think of the persistence of practices and experiences in its context, and the fact that landscape destruction is never total: rather, it is transformation. What’s more, the time of the landscape also includes non-human time scales, such as geology, climatology, and vegetation. They are temporalities to which we are nonetheless closely linked. Thus, in reality, the landscape remains in constant tension between past and present.

“Our era,” Jean-Marc Besse concludes, “is one of a crisis of attention. […] Landscape seems to be one of the ‘places’ where the prospect of a ‘correspondence’ with the world can be rediscovered […]. In other words, the landscape […] can be seen as a device for paying attention to reality, and thus as a fundamental condition for activating or reactivating a sensitive and meaningful relationship with the surrounding world”, in other words, the necessity of the landscape.

Vivre le Rhône: part 3

River Guardians

In July 2023, as part of Vivre le Rhône project, NLC and least organised in Geneva a three days series of events to expand a legitimate community acting on behalf of the river. A video by Carlos Tapia shows how it all unfolded.

Click here for part 1.

Click here for part 2.

Voices:

Maria Lucia Cruz Correia - artist

Marine Calmet - rights of nature

Floriane Facchini - artist / director

Vinny Jones - sensorial scenography

Felix Küchler - doctor, climate activist

Emma-Louise Lavigne - Association id-eau

Gilles Mulhauser Canton de Genève - Office cantonal de l’eau

Laurence Piaget-Dubuis - eco-artist, graphic designer, photographer

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 03

Vivre le Rhône: a podcast by Audrey Bersier and Martin Reinartz

Dear listener,

Since June 2022, the Natural Contract Lab and least have been deploying practices of walking-with, collective weaving, healing rituals, somatic experiences and restorative circles, all of which have enabled us to rethink our relationship with the Rhone.

What you are about to hear is the final episode in a three-part series, recounting the experiences of those who have grown closer to the river through these walks.

Although this episode marks the end of a collective journey between us and the Rhône, it is not the end of the adventure, because water has no beginning and no end, and the Rhône flows through each and every one of us.

To listen to this podcast, I would like to invite you to connect with water. Head to the bank of your favourite river, walk in the rain, look out at the sea or pour yourself a glass of water and drink it with awareness. Enjoy!

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 03

Listen to part 01.

Listen to part 02.

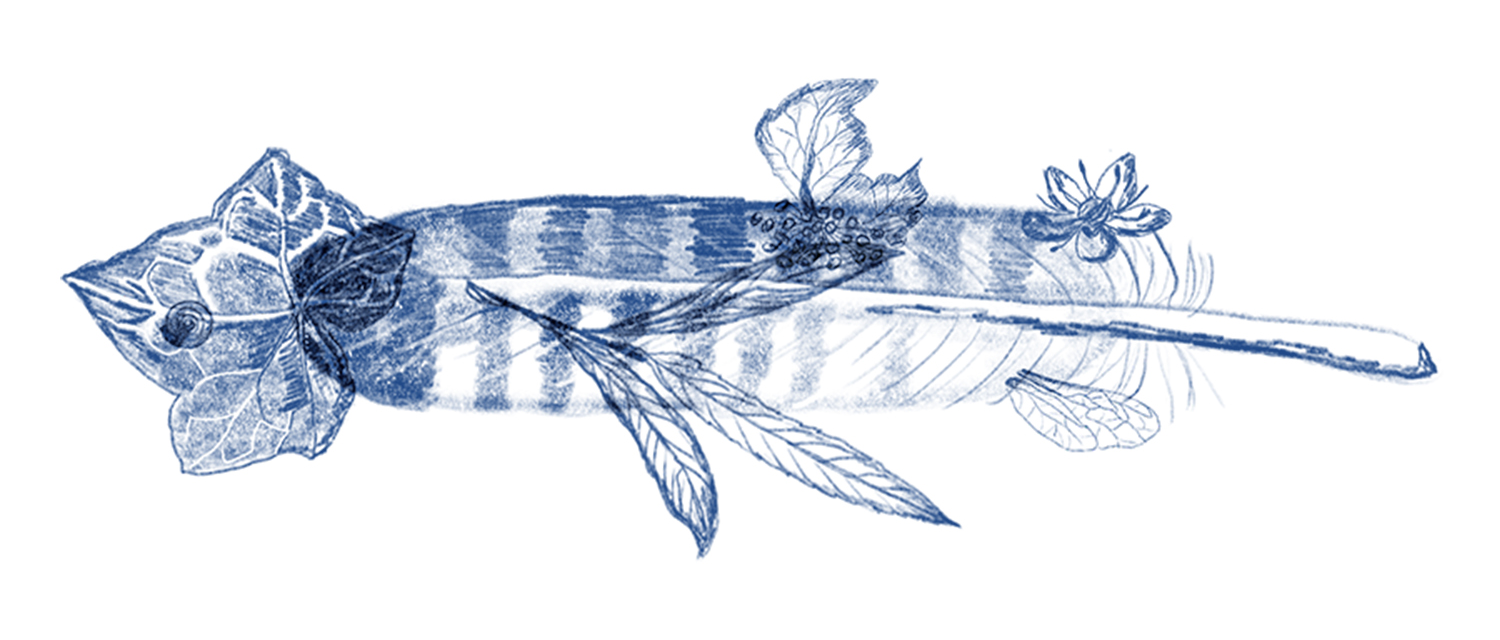

Vegetaltrout by Maud Abbé-Decarroux.

With texts inspired by Marielle Macé’s Nos Cabanes.

*Every effort was made to obtain the necessary permissions and to trace the copyright holders. However, we would be happy to arrange for permission to reproduce the material contained in this podcast from those copyright holders that we could not reach.

Supported by Fondation d’entreprise Hermès and Fondation Jan Michalski.

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 02

Vivre le Rhône: a podcast by Audrey Bersier and Martin Reinartz

Dear Listener,

Since June 2022, Natural Contract LAB and least have been developing accompanied walks, collective weaving, healing rituals, somatic experiences and restorative circles—all practices that have helped us rethink humans’ relationship with the Rhône.

What you’re about to hear is the first episode of a three-part podcast, retracing the experiences of those who have grown closer to the river by walking.

I’d like to give you a few tips before you start listening to this podcast.

If you can, head to Vernier Village in the Geneva countryside. Take some good headphones with you and your water bottle with water or your favourite herbal tea. Once you’ve arrived, start playing the audio.

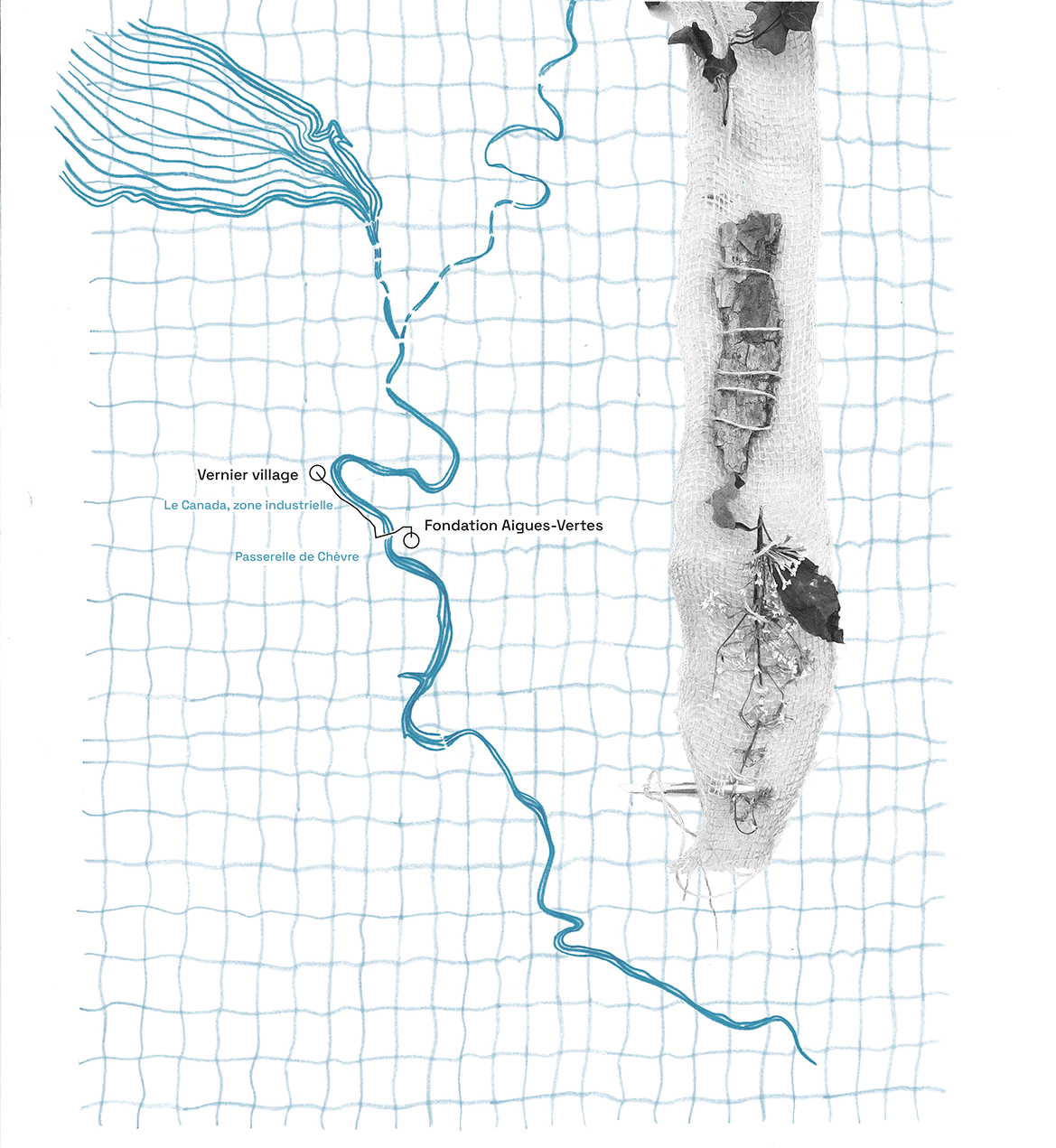

You can then walk down to the river and take the Chèvres footbridge, as shown on the map below.

Or you can simply sit down in a spot that you like. And close your eyes.

Enjoy the podcast!

Episode 02

Listen to part 01.

Listen to part 03.

Map by Maud Abbé-Decarroux.

*Every effort was made to obtain the necessary permissions and to trace the copyright holders. However, we would be happy to arrange for permission to reproduce the material contained in this podcast from those copyright holders that we could not reach.

Supported by Fondation d’entreprise Hermès and Fondation Jan Michalski.

Vivre le Rhône: part 2

Who has the legitimacy to speak for the river?

Vivre le Rhône’s initiator Maria Lucia Cruz Correia, environmental lawyer Marine Calmet and least’s artist-in-residence Martin Reinartz talk about rights of nature and river stewardship. June 2023.

Click here for part 1.

Click here for part 3.

Guardians of Nature

Trained as a lawyer, Marine Calmet specialises in issues relating to the protection of the environment and indigenous peoples. She is also president of Wild Legal, an association dedicated to the recognition of the rights of nature, and the author of Devenir Gardiens de la Nature (Becoming Guardians of Nature), which inspired her battles in French Guiana against illegal gold mines and the oil and gas industry. She is part of Vivre le Rhône’s Natural Contract Lab team.

When it comes to the rights of nature, a question often arises: who is in a legitimate position to speak on behalf of an ecosystem?

I think it’s very much linked to the idea that, in our societies, we have specific roles and statuses. Personally, I like to turn the question on its head. It’s more a question of asking ourselves what we live for and what our mission is in our society. I think that we can all legitimately represent natural entities, quite simply because of the responsibility that comes with living on this planet, in a living environment, and therefore being able to have a more or less strong relationship with a river, a forest or a mountain. For me, legitimacy comes from the bond of empathy, of love even, that exists between us and the environment in which we live and with which we interact. My aim is to deconstruct the myth that we don’t have the legitimacy or the capacity to speak on behalf of nature by asking the following question: what nature are we talking about? Are there not ecosystems to which we are so close and whose interests we feel a responsibility to defend?

What is the role of rights of nature in river governance from your point of view?

The aim of the rights of nature model is to prevent humans from viewing elements of nature as objects, which leads us to objectify our relationship with them and consider all beings around us as exploitable resources and goods that we can also destroy, and from which we can benefit for human progress and for society. The aim is also to challenge this relationship of objectification by considering elements of nature as subjects, legal subjects even, i.e. subjects who are protected or who should be protected and benefit from fundamental rights inherent in their status as subjects. This is where the law comes in, to clarify these relationships which, in truth, for many of us have never really been specified.

The law of nature tells us: “We’re surrounded by subjects to whom we also owe a certain form of respect and with whom interactions must be protected so that the habitability of ecosystems is preserved and this living space of ours remains serene and harmonious”.

In this governance that we’re calling for – this governance of the living – the aim is therefore to integrate other-than-humans, so that, instead of a dialogue strictly between human beings, we can open up the debate to non-humans and integrate them into our models of representation. This will enable us to emerge from what’s known as the Anthropocene – an Anthropocene that is nothing more than human self-segregation – and to integrate non-humans into this governance. This can only be done by recognising nature and all its elements as subjects in their own right and not as objects, because you can’t talk with objects.

You, as a lawyer, cooperate with artists: how can these two seemingly distant perspectives come together in a positive way? How do they impact each other?

What I find fascinating about the interaction between art and law is the similarities that emerge. As a lawyer, I work on what is known as “prospective law”, i.e. law that anticipates the future. I write law, I invent law, based on what I observe in nature and the needs or crises that I observe. As a lawyer, I therefore also work with fiction, writing something that I imagine or that I consider desirable. I’m acting like an artist who projects their vision of the world onto a canvas or a stage, but I’m doing so within a specific circle, i.e. the law. The law, like art, is therefore a set of fictional works that relate to a form of aestheticism. I consider myself to be more of an artist than a lawyer, because I’m in the creative process, a form of free creation that leads me to follow my instincts.

What I really like about working with Maria Lucia Cruz Correia and Natural Contract Lab is that she often points me in directions that I hadn’t thought of, or that I perhaps sometimes tended to think of in too legal a way, too focused on what already exists, on what we call positive law, i.e. what’s already there, instead of thinking outside this framework, taking inspiration and creating differently. Very often, this allows me to make huge leaps forwards in this profession of mine, because it allows me to open doors that I hadn’t imagined.

There’s a very strong link here. Just as artists are capable of thinking things that were previously unthinkable, in the legal world this allows me to make enormous progress. It’s also a way of making the law accessible to everyone, which is more in keeping with the artistic perspective.

It’s also interesting to get a message across. People see what the law is. Sometimes they’re a bit afraid of it and using it in an artistic perspective is an interesting way of linking it to a political context and a vision, that of building a new ideal. So I think there are some really interesting bridges between art and law, particularly through the pleadings we build together. Pleading is rhetoric, and rhetoric is the art of convincing others. Whether in the theatre or in the courts, we’re also here to convince, in a way, and to get our message across. There are inherent, very strong links between artists and lawyers that allow us to mutually enrich one another.

Bodies of Water

The transition of life from water to land is one of the most significant evolutionary milestones in the history of life on Earth. This transition occurred over millions of years as early aquatic organisms adapted to the challenges and opportunities presented by the terrestrial environment. One of those was the need to conserve water: living beings, in a way, had “to take the sea within them”, and yet, although our bodies are composed mostly of it, biological water actually counts for just 0.0001% of Earth’s total water.

Water is involved in many of the body’s essential functions, including digestion, circulation and temperature regulation. Nevertheless, our bodily fluids, from sweat to pee, saliva and tears, are not just contained within our individual bodies but are part of a more extensive system that includes all life on Earth, blurring the boundaries between our bodies and more-than-human organisms, connecting us to the world around us. Scholars described this idea as hypersea: the fluids that flow through our bodies are connected to the oceans, rivers and other bodies of water that make up the planet and are part of a larger system that connects all living beings together.

Recognising the interconnectedness of all life on Earth and the role that water plays in this interconnected web can help us better understand our place in the world and the importance of working together to protect and preserve this precious element. However, to fully grasp the consequences of this perspective, it is necessary to consider some significant issues addressed by scholar Astrida Neimanis, the theorist of hydrofeminism, in her book Bodies of Water.

One of the main contributions of hydrofeminism to the discussion on bodies of water is the proposal to reject the abstract idea of water to which we are accustomed. Water is usually described as an odourless, tasteless and colourless liquid and is told through a schematic and de-territorialised cycle that does not effectively represent the ever-changing, yet situated, reality of water bodies. Water is mainly interpreted as a neutral resource to be managed and consumed, even though it is a complex and powerful element that affects our identities, communities and relationships. Deep inequalities exist in our current water systems, shaped by social, economic and political structures.

Neimanis shares an example explicitly related to bodily fluids. The Mothers’ Milk project, led by Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook, found that women living on the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation had a 200% greater concentration of PCBs in their breast milk due to the dumping of General Motors’ sludge in nearby pits. Pollutants such as POPs hitch a ride on atmospheric currents and settle in the Arctic, where they concentrate in the food chain and are consumed by Arctic communities. As a result, the breast milk of Inuit women contains two to ten times the amount of organochlorine concentrations compared to samples from women in southern regions. This “body burden” has health risks and affects these lactating bodies’ psychological and spiritual well-being. The dumping of PCBs was a human decision, but the permeability of the ground, the river’s path and the fish’s appetite are caught in these currents, making it a multispecies issue.

Hence, even though we are all in the same storm, we are not all in the same boat. The experience of water is shaped by cultural and social factors, such as gender, race and class, which can affect access to safe water and the ability to participate in water management. The story of Inuit women makes it clear how water, even if it is part of a single planetary cycle, is always embodied, and so are bodies of water with their complex interdependence. While hydrofeminism invites us to reject an individualistic and static perspective, it also reminds us that differences should be recognised and respected. Indeed, it is only in this way that thought can be transformed into action towards more equitable and sustainable relationships with all entities.

Neimanis also approaches the role of water as a gestational element, a metaphor for this life-giving substance’s transformative yet mysterious power. Like the amniotic fluid that surrounds and nurtures a growing animal, water can support and sustain life, nourish and protect, and foster growth and development. In this sense, water can be seen as a symbol of hope and possibility, a source of renewal and regeneration that can help us navigate life’s challenges and transitions. Like a gestational element, water has the power to cleanse, heal and transform. While seeking to find our way in a constantly changing world, we can look to water as an inner source of strength and inspiration, a reminder of life’s resistance and adaptability and the potential that lies within us all.

Image: Edward Burtynsky, Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, Baja, Mexico, 2012. Photo © Edward Burtynsky.

Vivre le Rhône: the podcast, part 01

Vivre le Rhône: a podcast by Audrey Bersier and Martin Reinartz

Dear Listener,

Since June 2022, Natural Contract LAB and least have been developing accompanied walks, collective weaving, healing rituals, somatic experiences and restorative circles—all practices that have helped us rethink humans’ relationship with the Rhône.

What you’re about to hear is the first episode of a three-parts podcast, recounting the experiences of those who have grown closer to the river by walking.

I’d like to give you a few tips before you start listening to this podcast.

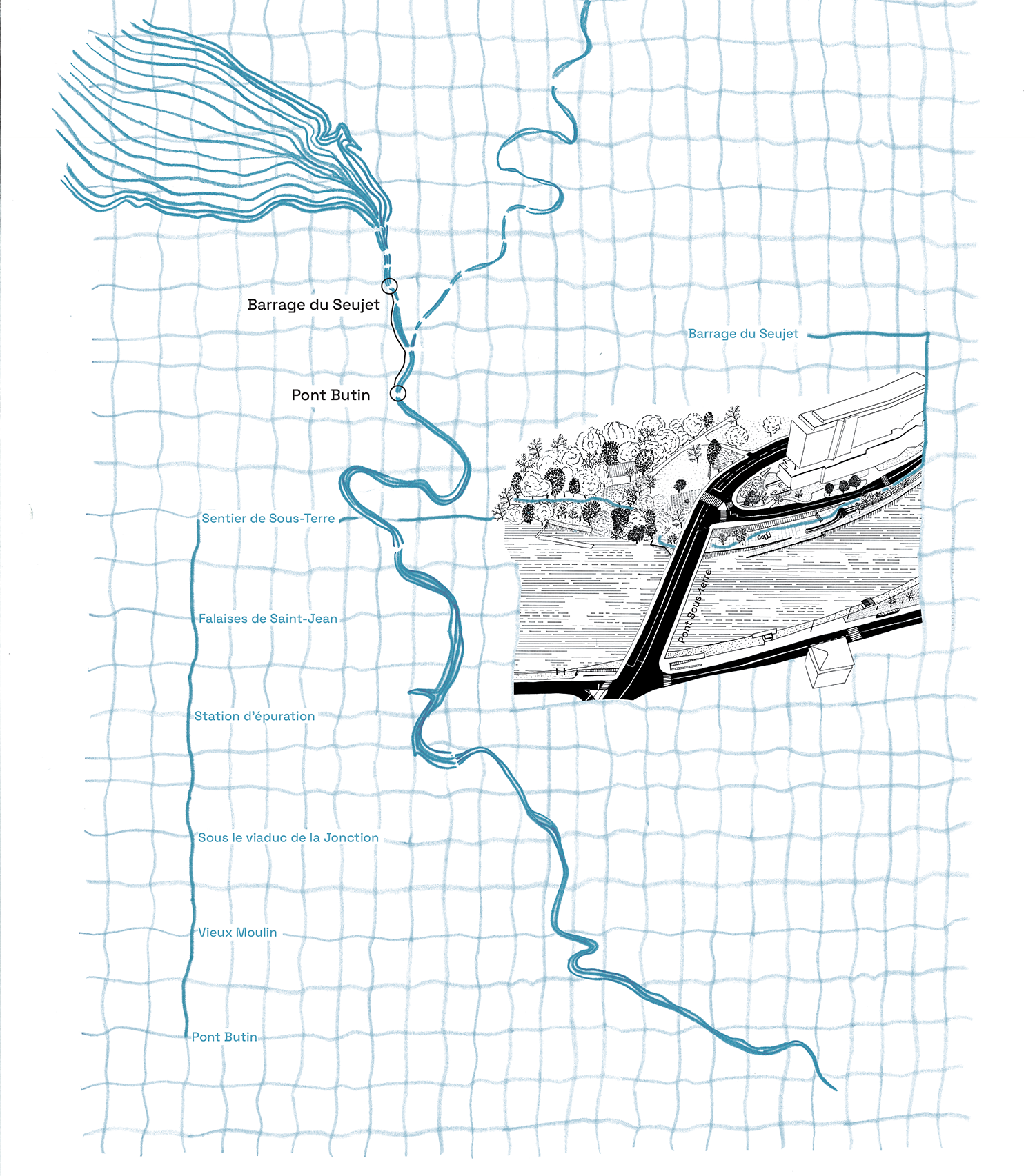

If you can, head to the Seujet dam, in downtown Geneva. Take some good headphones, writing materials and a bottle filled with water or your favourite herbal tea. Once there, start the podcast.

It’s up to you whether you choose to stay on the dam or walk along the river, towards Pont Butin for example, as shown on the map below.

Or you can simply sit down in a spot that you like. And close your eyes.

Enjoy the podcast!

Episode 01

Featuring texts freely inspired by Corinna S. Bille’s L’inconnue du Haut-Rhone and Les Soeurs Caramarcaz, as well as Alexandre Dumas’ Voyage Suisse.

Map by Maud Abbé-Decarroux.

Listen to part 02.

Listen to part 03.

*Every effort was made to obtain the necessary permissions and to trace the copyright holders. However, we would be happy to arrange for permission to reproduce the material contained in this podcast from those copyright holders that we could not reach.

Supported by Fondation d’entreprise Hermès and Fondation Jan Michalski.

Putting Off the Catastrophe

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously? How can we overcome the apathy of our eternal present? The following article is taken from MEDUSA, an Italian newsletter that talks about climate and cultural changes. Edited by Matteo De Giuli and Nicolò Porcelluzzi in collaboration with NOT, it comes out every second Wednesday and you can register for it here. In 2021, MEDUSA also became a book.

There is no alternative was one of Margaret Thatcher’s slogans: wellbeing, services, economic growth… are goals achievable exclusively by doing things the free market way. 40 years on, in a world built on those very election promises, There is no alternative sounds more like a bleak statement of fact, a maxim curbing our collective imagination: there is no alternative to the system we’re living in. Even when we’re hit by crisis, in times of unrest, exploitation and inequality, the state of affairs finds us more or less defenceless. There’s no escape – or we can’t see it: our room for manoeuvre has been fenced off.

Why can’t we take global warming seriously? Because it’s one of those complex systems that operate, as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams affirm in their Inventing the Future, “on temporal and spatial scales that go well beyond the bare perceptual capacities of the individual” and whose effects “are so widespread that it’s impossible to exactly collocate our experience within their context”. In short, the climate problem is also the result of a cognitive problem. We are lost in the corridors of a vast and complex building in which we see no direct and immediate reaction to anything we do and have no clear moral compass to help us find our way.

It was to pursue these issues further that I decided to read What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming (hereafter WWTAWWTNTAGW) by Norwegian psychologist and economist Per Espen Stoknes, a book I’d been putting off reading for some time for a series of reasons that turned out to be only partially valid. First of all, there was my vaguely scientist prejudice: despite being interested in the issue, I find that the back cover of WWTAWWTNTAGW sounds more like front flap blurb for some self-help publication rather than for a serious work of popular science. I quote: “Stoknes shows how to retell the story of climate change and at the same time create positive, meaningful actions that can be supported even by negationists”. Then there was the title, WWTAWWTNTAGW, a cumbersome paraphrase of a title that is already, in itself, the most ferociously paraphrased in the history of world literature. And lastly — still on the surface only – there was the spectre of another book by Per Espen Stoknes, published in 2009, the mere cover of which I continue to find insurmountably cringeful: Money & Soul: A New Balance Between Finance and Feelings.

Laying aside, for the moment at least, the prejudices that kept me away from WWTAWWTNTAGW, I discovered a light-handed book that raises various interesting points. In short: why does climate change, our future, interest us so little? Why do we see it as such an abstract and remote problem? What are the cognitive barriers that are sedating, tranquillizing and preventing us from having even the slightest real fear for the fate of the planet? Stoknes identifies five, which can be summed up more or less as follows:

Distance. The climate problem is still remote for many of us, from various points of view. Floods, droughts, bushfires are increasingly frequent but still affect only a small part of the planet. The bigger impacts are still far off in time, a century or more.

Doom. Climate change is spoken of as an unavoidable disaster that will cause losses, costs and sacrifices: it is human instinct to avoid such matters. We are predictably averse to grief. Lack of practical solutions on offer exacerbates feelings of impotence, while messages of catastrophe backfire. We’ve been told that “the end is nigh” so many times that it no longer worries us.

Dissonance. When what we know (using fossil fuel energy contributes to global warming) comes into conflict with what we’re forced to do or what we end up doing anyway (driving, flying, eating beef), we feel cognitive dissonance. To shake this off, we are driven to challenge or underestimate the things we are sure about (facts) in order to be able to go about our daily lives with greater ease.

Denial. When we deny, ignore or avoid acknowledging certain disturbing facts that we know to be “true” about climate change, we are shielding ourselves against the fear and feelings of guilt that they generate, against attacks on our lifestyle. Denial is a self-defence mechanism and is different from ignorance, stupidity or lack of information.

Identity. We filter news through our personal and cultural identities. We look for information that endorses values and presuppositions already inside our minds. Cultural identity overwrites facts. If new information requires us to change ourselves, we probably won’t accept it. We balk at calls to change our personal identities.

There are obviously hundreds of other reasons why we still hold back from a strategy to mitigate climate change: economic interests, the slowness of diplomacy, conflicting development models, the United States, India, sheer egoism, “great derangement” and all the other things we’ve come to know so well over the years. But Per Espen Stoknes empirically suggests a way forward. Catastrophism and alarmism don’t work. We need to find a different tone to dispel the apathy of our eternal present.

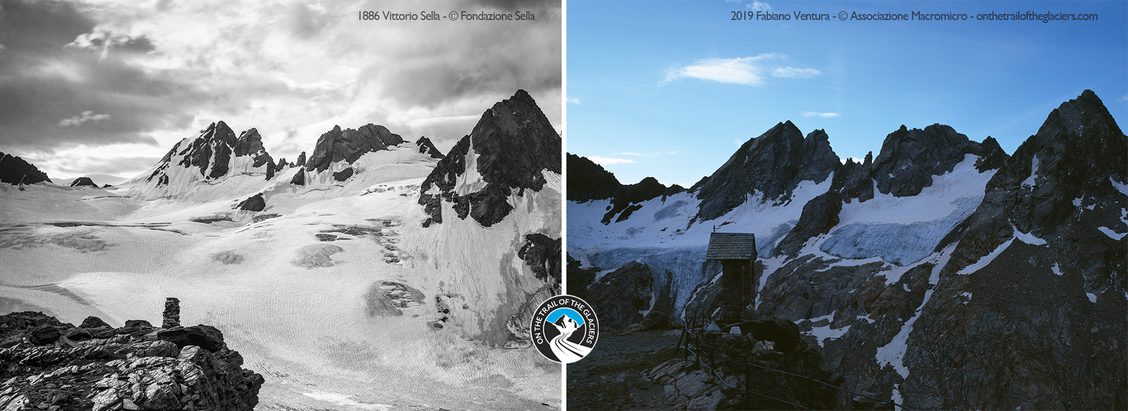

Image: The Grosser Aletsch, 1900 Photoglob Wehrli © Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung und Fotoarchiv/ 2021 Fabiano Ventura – © Associazione Macromicro.

A urge to do something

Can you briefly tell us something about you, and how you became an eco-activist?

I wouldn’t say I’m an activist. Apart from my role as co-president, I’m an elected representative in the parliament of my city. I’ve also created an ecofeminist collective with two friends in Biel, called “La Bise”. And I earn my income as an early childhood nurse. Shortly before I turned 18, I felt a strong urge to do something. Or at least to try. I can’t really say what triggered this need to act. I started my political involvement in a small group of young greens. Then one day things just happened. I was asked if I wanted to join an electoral list. I accepted, and I was elected. This event helped me to network and find people with whom I could exchange, militate, and initiate new projects.

What is the state of health of Swiss glaciers? And why is it important to take care of glaciers in particular?

The state of the glaciers in Switzerland is disastrous. With the melting of the glaciers, Switzerland is losing (among other things like its biodiversity and its snow in winter) an important water reserve which, according to estimates, could guarantee the consumption of its population for 60 years.

Part of the resistance to revolutions such as abandoning fossil fuels is linked to economic interests. Let’s play a game of scenarios: with and without fossil fuels, in the short and long term.

Growth can’t be infinite; it leads to our own destruction. Independence from fossil fuels requires support for other forms of energy sources. In Switzerland, electricity is mainly generated by hydroelectric power plants (62%), nuclear power plants (29%), conventional thermal power plants and renewable energy plants (9%). By producing our own energy, we’re no longer dependent on other countries. This is an opportunity for States to become pioneers and create jobs in new areas. So it’s also good for the economy.

Environmental protection is a complex subject – sometimes to fix one mistake you make another. What is your strategy for dealing with this complexity?

I think if you keep thinking about what you’re going to do wrong, you don’t move forward with strategies that have a real impact. You can’t always do everything right. But you can put in place things that have a strong impact for long term change. Like long-term independence from imported energy sources that are harmful to the planet.

Solastalgia is the distress caused by the impact of climate change on people, often involving the feeling of loss of a beloved landscape. Do you feel that you’re suffering from solastalgia? And what’s your experience of this issue in Swiss communities?

Solastalgia is a relatively unknown term. But by talking to people living in wilder and alpine regions, solastalgia for a disappeared or changed landscape can be identified. Sensitivities to climate change are as diverse as the regions of Switzerland. The place of origin of a person influences the way he or she reacts to the consequences of this change. It seems natural to be more affected by the lack of snow in winter or the melting of glaciers if you live or grew up in an alpine environment. People who live in cities, for example, are more aware of urban heat islands and increasing suffocation in summer. At the moment, I think I suffer more from eco-anxiety than from solastalgia.

You’re part of the eco-feminist collective La Bise: can you tell us about the activities of La Bise and what eco-feminist instances contribute in particular to the general fight against the climate crisis?

La Bise is a collective that tries to bring struggles together. The collective was created almost five years ago. Talking with two of my friends about what animated or annoyed us in feminist and ecological struggles, I felt like bringing the three of us together. The idea of creating a caring and inclusive space to talk about our commitments was at the heart of our draft project. At first, we were mobile, we didn’t have a place. Then we were able to create our ecofeminist library. The library contains books in several categories. Feminism and gender, sexuality, children’s books, comics. We have an ecofeminist library, but we also organise more or less regular events that link the fight for the protection of the planet and the fight for gender equality.

Several studies show that women and gender minorities are among the human beings most affected by climate change. To give an example: women and gender minorities are frequently forgotten during natural disasters – often because it is these same people who actually take care of others.

Vivre le Rhône: part 1

“What stories are already there?”

A video by Carlos Tapia featuring the Rhône river, Maria Lucia Cruz Correia, Vinny Jones, and Lode Vranken. February 2023.

Click here for part 2.

Click here for part 3.

press

Explore tomorrow, at the heart of public debate

Tribune de Genève, 04/22/2024

Permaculture, the ecological model to reinvent culture

L’Hebdo du quotidien de l’art, 02/09/2024

Becoming a guardian of the Rhône

Le Courrier, 07/20/2023

«Vivre le Rhône», a civic and artistic initiative

Le Temps, 07/07/2023

Weaving Subjects at MACO

«Vivre le Rhône» celebrates the identity of the river

Tribune de Genève, 07/13/2023

The Rhône seeks guardians

Le Courrier, 07/12/2023

An initiative to accompany our society in its transformation

Kunstbulletin 5/2023