laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School is a project that focused on survival, the commons, and hopes and strategies for addressing climate change and the Anthropocene. As the future holds more extreme environments and increasingly urbanised spaces, only the most resilient species will be able to adapt to life. This project has allowed us to share our desires and inspirations to envision shelters and alternative ways of being in an endangered world.

least and artist Maria Lucia Cruz Correia asked a class of 3rd-year students from Collège Sismondi (Geneva) to imagine this adaptation by suggesting alternatives. On a specifically designed “shelter island”, they rethought ways of living together, acting in common and creating new possibilities, tackling themes ranging from the most concrete to the most philosophical: community values, working together, food, resources, the economy, energy, emotional resilience, place of care, governance and social life.

The “island” was designed by the students and built in conjunction with craftspeople and carpenters. Biologists, climatologists, engineers, activists, farmers and commons experts were invited throughout the process to participate in the design and activation of this “Flotation School”.

“The shelter island is the first public project of the association least, which mixes ecology and art to respond to environmental and societal issues […]”

researching, imagining, building

From autumn 2022 to end of 2023, Maria Lucia Cruz Correia, least’s artist-in-residence Maxime Gorbatchevsky and the team at least met regularly with students from Collège Sismondi to reflect on new ways of living and acting together in order to tackle climate change. The students were introduced to these issues by experts from different disciplines (engineering, biology, architecture, permaculture, nutrition, performance). The students were then involved in the hands-on construction of amenities for the island based on their models, while the floating structure was built in cooperation with carpenters and young apprentices from Ateliers ABX.

a school surrounded by water

On 24 April 2023, Common Dreams: Flotation School Panarea was launched on the waters of Lake Geneva at Perle du Lac. The students curated and organised a programme of activities and open workshops that took place on the platform throughout May. The workshops related to EARTH (architecture/shelter/ temporary space), AIR (resources/economy/food/ energy), FIRE (community/ place of care/governance), WATER (social resilience/emotional/climate grief) and SPIRIT (survival/earth wisdom/animism). The platform was also used as an open, aquatic classroom by students and teachers from a number of schools and universities, including HEPIA.

the open programme

An open call for associations, collectives and individuals to use the platform to create or reflect on the project’s themes was launched throughout the summer 2023. From June onwards, Common Dreams: Flotation School Panarea was included in the BIG (Biennale Insulaire des Espaces d’Art de Genève) programme and made available to Maxime Gorbatchevsky, artist in residence at least, as a venue for his artistic practice.

the second life of the platform

In autumn 2023, in collaboration with the Cantonal Office for Agriculture and Nature (OCAN) and EPFL, the Common Dreams project continued with the reuse and transformation by first-year architecture students at EPFL (ALICE – Space Design Laboratory). Working closely with students from Collège Sismondi, several elements of the platform have been recovered and converted into three wooden seating platforms of varying heights, for relaxation and observation in Geneva’s Parc Rigot. Inaugurated in May 2024, this pop-up installation serves as a tool for sharing experiences with the local human and more-than-human community.

newsletter

Stay up to date about our latest activities, articles, inspirations and much more!

artistic team

Maria Lucia Cruz Correia – founder and artistic coordinator

Maxime Gorbatchevsky – artist-in-residence at least

Sismondi College Team

Adrien Beck - visual arts

Céline Hetherington - dean

Nathalie Novarina - visual arts

Alexandra Sonntag - art history

Eric Tamone - director

Sismondi College Students

Arthur Arlaud; Dylan Burri; Timothée Castilla; Matias Chappot; Helena Delruelle; Jules Dubes-Plun; Camélya Dumitrescu; Annette Fivaz; Odelia Forster; Mathilde Grand-Guillaume-Perrenoud; Anouk Grange; Colette Heinen; Naïka Ilunga; Elya-Sirine Itsouhou; Guillem Jehouda; Fabio Mazzaferri; Mykola Protsenko; Naomé Valere; Marine Re; Emma Rigueiro Brand; Louise Schachter; Ilan Sela; Flavio Viggiani; Louis Wyss.

least would like to thank all the people who contributed to the project by sharing their time, knowledge, and resources:

Maud Abbé-Decarroux (architect); Marcio Bichsel (civil engineer) / B+S Ingénieurs; Audrey Bersier (sound artist); Julien Besse (jurist); Luc Bon, Flavio, Jérémy and the young people of Ateliers ABX (woodworkers-carpenters); Pierre Bratschi (astronomer); Tiphaine Bussy-Blunier (landscape architect) / Canton de Genève- Office cantonal de l’agriculture et de la nature; Olga Cebalos (biologist) / Association la Libellule; Grace Denis (artist); EPFL, Atelier Alice; Sophie Frezza; Léo Gaugué-Natorp (artist); Kimberly Hirsch; Bilal Kouti (agroforestry) / Le Bois des 3 Sœurs; Al Mammana (artist); Christelle Marro Valère (yoga teacher); Adrien Mésot (artist-harvester) / Au Diable vert; Rita Natálio (artist, researcher) / Terra Batida; Alexandra Slotte (artist); Carlos Tapia (videomaker); Zsolt Vecsernyes (civil engineer) / HEPIA.

media

Ô noble Green

Reading

The «Ignota Lingua» by Hildegarde of Bingen.

CROSS FRUIT

Common Dreams

Faire commun

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Reading

Yves Citton discusses commons, negative commons, and sub-commons with us.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Listenting to the Sourdough

Reading

An interview with the artist and scholar Marie Preston on cooperative practice and including the more-than-human.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Bodies of Water

Reading

Embracing hydrofeminism.

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

Intimity Among Strangers

Reading

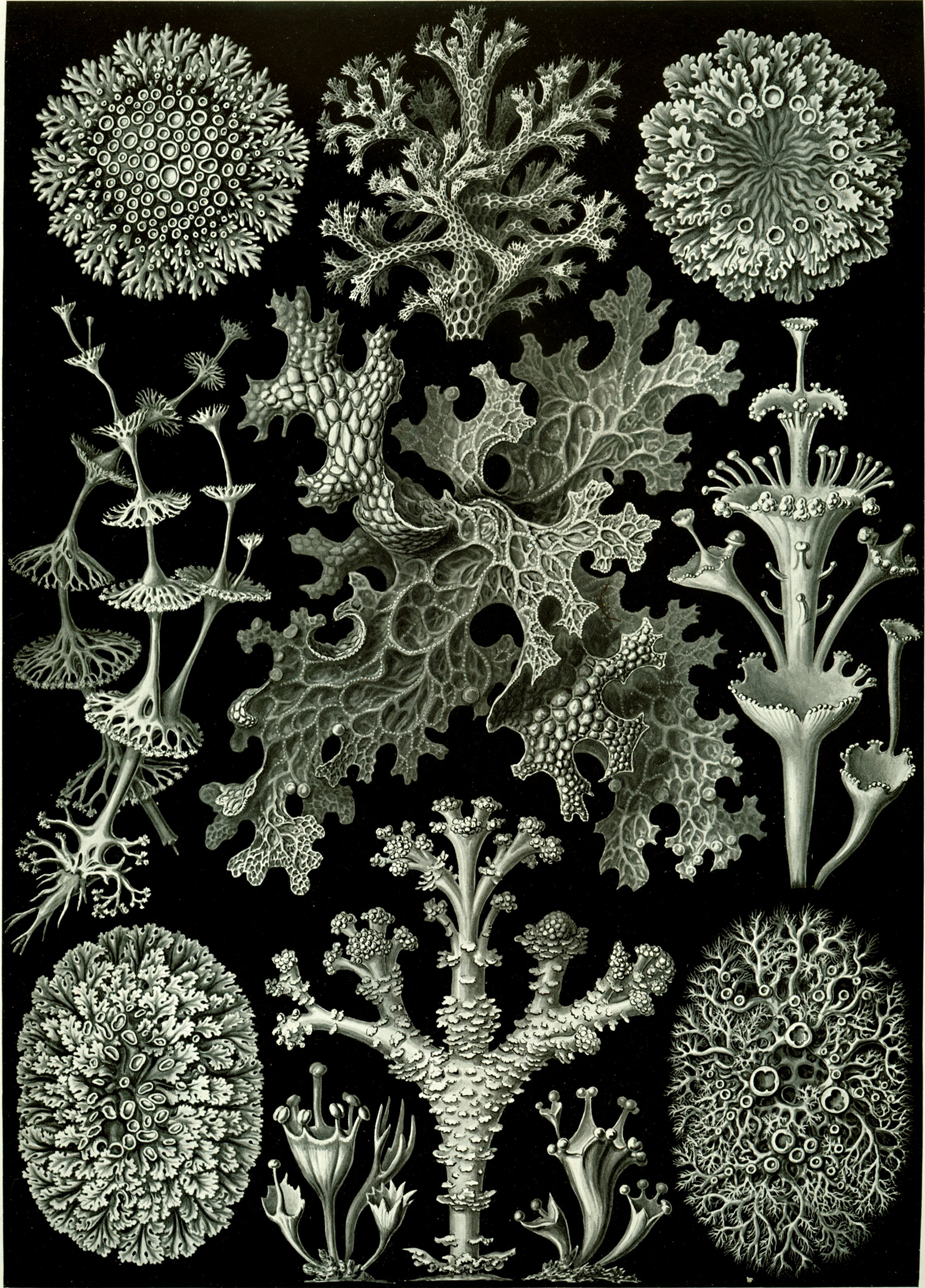

Lichens tell of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option

Common Dreams

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

A Sub-Optimal World

Reading

An interview with Olivier Hamant, author of the book “La troisième voie du vivant”.

Common Dreams

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Putting Off the Catastrophe

Reading

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously?

Common Dreams

Vivre le Rhône

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Video

The video of the project Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School.

Common Dreams

Ô noble Green

O noble Green, rooted in the sun

and shining in clear serenity,

in the round of a rotating wheel

which cannot contain all the earth’s magnificence,

you Green, you are wrapped in love,

embraced by the power of celestial secrets.

You blush like the light of dawn

you burn like the embers of the sun,

O most noble Viriditas.

This magnificent hymn to the creative power of “green” is a responsory written and set to music by one of the most brilliant minds of medieval Europe: Hildegard of Bingen, a Christian saint and mystic who lived in the Rhineland in the early 12th century. The tenth daughter of a noble family, from an early age Hildegard was subject to visions and migraines, and for this reason she was destined for the convent already at the age of thirteen. She would only confess and publicly describe her visions at the age of forty-three, prompted by a divine order; a few years later, she founded the monastery of Bingen, of which she was abbess.

Hildegard’s merits are countless: she is the first Western female composer of whom we have written testimony, and her body of music is the most substantial of the era in which she lived to have come down to us. She was an excellent naturalist: her mighty treatise Physica includes 230 chapters on plants, 63 chapters on elements, 63 chapters on trees, and many more on stones, fish, birds, reptiles, and metals, enriched with indications of their medicinal properties: for this reason, some consider her the founder of naturopathy. Her homilies and speeches, imbued with a form of revolutionary vitalism that was unknown to the ecclesiastical thinking of the time, were encouraged and even published with the support of powerful popes and prelates such as Bernard of Clairvaux – a truly exceptional fact in the profoundly misogynistic context of medieval Europe.

Hildegard, however, encountered some difficulty in describing her visions: “In my visions, I was not taught to write like the philosophers. Moreover, the words I see and hear in my visions are not like the words of human language but are like a burning flame or a cloud moving through the clear air.” How do you convey something that cannot be spoken? How do you give voice to new concepts, unknown to the theologians and wise men of the time? How do you criticise the very structure of current thought? Hildegard did not choose the easy way, but decided to invent a new language, which she called Ignota Lingua and which is considered one of the first “artificial languages” ever created (Hildegard is in fact considered the patron saint of Esperanto). Her “dictionary” is actually a glossary of 1011 words, mostly transcribed into Latin and medieval German with the help of a scribe.

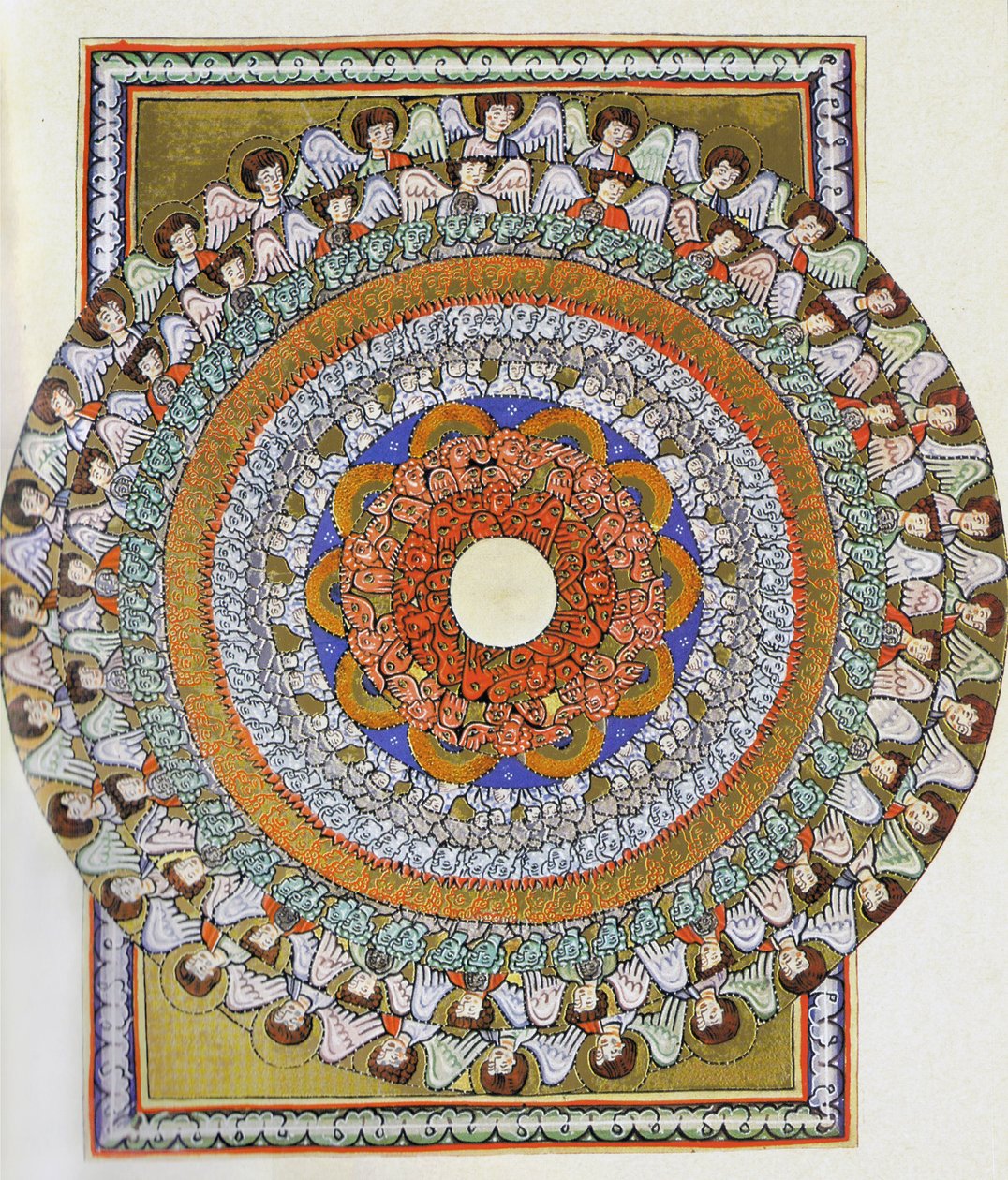

Image: Hildegard of Bingen, The hierarchy of angels, sixth vision of the Scivias manuscript.

Among many wonderful linguistic inventions, the concept of viriditas recurs in her writings. Scholar Sarah L. Higley attempts a translation: “viriditas, ‘greenness’ or ‘greening power’, or even ‘vitality’, is associated with all that partakes of God’s living presence, including blossoming nature, the very sap (sudor, ‘sweat’) that fills out leaves and shoots. It is (…) closely associated with humiditas, moisture. Hildegard writes (…) that ‘the grace of God glitters like the sun and sends forth its gifts variously: one way in wisdom (sapientia), another in viridity (uiriditate), a third in moisture (humiditate). In her letter to Tenxwind she compares the virginal beauty of woman to the earth, which exudes (sudat) the greenness or vitality of the grass. The Virgin Mary, of course, is viridissima virga, the ‘greenest branch,’ in Hildegard’s Symphonia. Aridity, on the other hand, represents incredulity, a lack of spirituality, the abandonment of the virtues in their greenness: that which withers and is consumed at the moment of Judgement.

For the inner eye of the mystical naturalist, capable of scrutinising the invisible in the visible, the whole of creation is a flow of divine, gushing green sap. Hildegard attached great importance to the colour green, a symbol of vigour, youth, creative power, efflorescence, fructification, fertilisation, and regeneration. Celebrating greenness for Hildegard is recognising that we are part of a whole, without separation, and serves to maintain the cohesion between soul and body. This radical thinking requires new words, new ways of thinking: inventing a language is an act that helps us understand that everything can be called into question, everything can be imagined from new premises.

Below is a selection of words of the Ignota Lingua from the chapter on trees (translated to English by Sarah L. Higley): an invitation to (re)think everything, starting with the most common words.

Lamischiz — FIR

Pazimbu — MEDLAR

Schalmindibiz — ALMOND

Bauschuz — MAPLE

Hamischa — ALDER

Laizscia — LINDEN

Scoibuz — BOXWOOD

Gramzibuz — CHESTNUT

Scoica — HORNBEAM

Bumbirich — HAZEL

Zaimzabuz — QUINCE

Gruzimbuz — CHERRY

Culmendiabuz — DOGWOOD

Guskaibuz — WINTER OAK

Gigunzibuz — FIG

Bizarmol — ASH

Zamzila — BEECH

Schoimchia — SPRUCE

Scongilbuz — SPINDLE-TREE

Clamizibuz — LAUREL

Gonizla — SHRUB?

Zaschibuz — MASTIC

Schalnihilbuz — JUNIPER

Pomziaz — APPLE

Mizamabuz — MULBERRY

Burschiabuz — TAMARISK

Laschiabuz — MOUNTAIN ASH

Golinzia — PLANE TREE

Sparinichibuz — PEACH

Zirunzibuz — PEAR

Burzimibuz — PLUM

Gimeldia — PINE

Noinz — CHRIST’S THORN

Lamschiz — ELDER

Scinzibuz — SAVIN SAVINE

Kisanzibuz — COTTON TREE

Vischobuz — YEW

Gulizbaz — BIRCH

Scoiaz — WILLOW

Wagiziaz — SALLOW

Scuanibuz — MYRTLE

Schirobuz — MAPLE

Orschibuz — OAK

Muzimibuz — WALNUT

Gisgiaz — CALTROP

Zizanz — BRIAR

Izziroz — THORN TREE

Gluuiz — REED

Ausiz — HEMLOCK

Florisca — BALSAM

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Swiss philosopher Yves Citton’s areas of research range from literature to media theory and political philosophy. We met him as part of our Faire Commun project to discuss a central theme of our research: the commons. Below is a transcript of part of his talk.

I’d like to introduce the “commons” by trying to qualify a certain image – which isn’t wrong, but quite partial – of the commons as pre-existing human appropriation. According to folklore, the Earth and its goods were shared by all animals and all featherless bipeds like ourselves. Then, according to Rousseau’s second discourse, human appropriation became the source of all evils.

This means that the commons are given as they are by nature. It’s true that the air we breathe, for example, wasn’t created by humans so that they wouldn’t die of asphyxiation: on Earth there is air, and we humans benefit from it. It’s a certain layer of the commons that we enjoy naturally, even if we don’t know exactly what nature means.

We can also say that air and water are quite similar commons. On Earth, there’s salt and fresh water, which is drinkable. But if you think about the reality of water today, the water we drink is more or less natural water. We know that it can contain chlorine, that it flows through pipes. Hence, to my mind, water isn’t at all a natural commons. It’s the result of an infrastructure, which can be public, private, or associative; it can be democratic or subject to capitalism. It’s mediated by the community or public institutions. In order to distinguish between public and private commons, I’d call this case public – a government has intervened, made regulations, and financed the pipes.

It’s still a commons, but one that has been constructed by humans, legislation, and political processes. Most of the time, when we talk about the commons today, these elements are inevitably involved. Even forests no longer look like they did before humans brought domesticated species and technologies into them. So I think it’s more realistic to say that the commons include a human artificialisation and preservation dimension. We don’t necessarily need to take care of the air – it’s enough not to pollute it – but we do need to preserve water, pipes, and infrastructures.

It’s interesting to consider another, slightly different model of the commons, i.e. language. Language didn’t precede humans, there was no French language 300,000 years ago; it isn’t an institution, nor an infrastructure regulated by a state that cares for and maintains it. French resides both within and between us. To my mind, it’s the most bizarre and extraordinary model of the commons, existing only because we own it: if all the people who speak French disappeared, there’d be no more French. (That’s without taking into account books written in French, which would remain of course). Knowing where a commons lies, whether it’s artificial or public, is no easy task. For me, what language highlights about the commons is the fact that it can exist without official regulation. The Académie française did not create the French language. Language is reproduced through culture and through children talking to their parents. It’s a commons: it’s neither totally public nor totally private.

Image: Mattia Pajè, Il mondo ha superato se stesso (again), 2020

The French language, air and water are elements that are necessary to our survival, and we’re grateful that they’re available to us: we can define them as positive commons. Conversely, there are negative commons, which are a continuation and a reversal of the latter. Researchers Alexandre Monnin, Diego Landivar, and Emmanuel Bonnet use the term “negative commons” to refer to nuclear waste, to cite only the most telling example. Whether a nuclear power station has public or private status doesn’t change the fact that the resulting waste becomes a collective problem for hundreds of thousands of years to come. It’s clear that nuclear waste is a commons, just as plastic and the climate are. Indeed, the climate, like water, is becoming an element that needs to be maintained if it’s to remain liveable. Some negative commons are therefore blending in with commons that were traditionally seen as positive. These negative commons pose a major problem: they feed our lives (the nuclear power station feeds my computer, which allows me to communicate) but they harm our living environments. Feeding and harming are seen as two sides of the same coin, at the same time. Nuclear energy provides me with electricity but harms future generations through the production of radioactivity.

If we develop this idea further, we can see finance as a good example of a negative commons: finance feeds our investments and the state budget but pollutes our environments by pushing to maximise profits at the expense of environmental considerations. How do we get out of this? How can we dismantle finance? It’s even more interesting to ask whether universities are not a negative commons: knowledge is developed, and research carried out, but the way universities operate can be toxic, with some teachers taking advantage of their power over their students, for example. There’s also bureaucracy that prevents us from doing good work at the same time as framing and structuring that work. There are toxic elements that need to be dismantled, but it’s not easy because they feed us. The intellectual exercise of projecting a negative commons hypothesis onto different subjects is therefore quite revealing.

There’s also the concept of undercommons, a term defined by Afro-American poet and philosopher Fred Moten and activist and researcher Stefano Harney. This term is based on the political ideas of the Black Radical Tradition in the United States. The over-representation of black people, particularly black men, in prisons in the United States today is dramatic, and there’s a continuity between slavery a few centuries ago and racial domination in this country today. The people who emerged from the slave holds were never considered as individuals in their own right. They therefore had to develop other modes of sociality, alternatives to the individualistic socialisation of the homo economicus, the small businessman, the white bourgeois. The communities that were threatened with lynching until a few decades ago and are now victims of police violence, live in conditions of marginalisation or at least do not enjoy the privileges that you and I, as white people in Switzerland or France, have been able to enjoy. These people have therefore developed an alternative, underground form of socialisation: a somewhat paralegal or semi-legal form of solidarity, since US law is made by white people for white people. Instead of seeing this form of solidarity as illegal, it might be seen as a different form of solidarity, outside the law, but one that is worthy of consideration and study. It enables ways of living that feed the commons, even if they’re less visible. And it could prove crucial for all of us: the infrastructures that sustain our luxuries and our forms of economic and social individualisation, as we know them today, may not last indefinitely. It would therefore be in our interests to familiarise ourselves with this form of “survival solidarity”. And of course, before doing so, it’s important to denounce and fight against the persistent oppression that weighs on marginalised populations.

I had the opportunity to work with Dominique Quessada, who came up with the idea of writing the term “commun” (commons in French) as “comme-un” (literally “as one”): his idea being that the commons belongs to everyone and to no one at the same time. The very fact of talking about the commons perhaps presupposes that the term is established, that there are people who see it as a real possibility, and that behind the dissolution of identity and property, the commons is something in which everyone can participate: it’s a plural, it’s neither mine nor yours. Above all, to write it “comme-un” suggests that the unity (of a certain people, of a community) that is often thought of as inherent to the commons is perhaps no more than “acting-as-if we were one”. Faced with the commons, we act “as one”, but we remain diverse, different, and sometimes antagonistic to one another.

Behind the commons there are always two concepts. First of all, there is the principle of unity: who are those who speak of a “commons”? On what do they base themselves? In reality, they can only defend a commons because they’re already united. Secondly, the commons is always a collective fiction: calling something a “commons” means that it is considered as such and thus develops characteristics of a commons. A public park is a public park because it is declared to be one. Thanks to this label, it’s possible to do things in this park that would otherwise have been impossible. But this remains a temporary fiction: a change of regime, a sale, an occupation of the site can always happen. In short, writing “comme-un”, or “as-one”, with a hyphen means asking two questions. Firstly, what is this unity, however heterogeneous, that allows us to say that there is a commons? Secondly, what is the fictional element, the dynamic that allows us to forge a concept that doesn’t exist? The imaginary dimension of the commons always remains central to its defence.

Listenting to the Sourdough

An interview on cooperative practices and how to include the more-than-human with Marie Preston, artist and lecturer at the University of Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis (TEAMeD/AIAC Laboratory). Her artistic work takes the form of research aimed at creating works and documents of experience with people who are not necessarily artists. In recent years, her research has focused on the practice of baking, open schools, and libertarian and institutional pedagogies, as well as on women working in the care and childcare sector.

How do co-creative practices compare with political or social participation?

According to philosopher Joëlle Zask, participation in politics should be a combination of taking part, contributing and receiving. Cooperative artistic practices open up spaces where experiences and opinions can be shared, something which is also common to politics. However, political participation aims for an explicit goal, unlike many cooperative artistic practices which are “indeterminate” at first and whose objectives can change through various encounters. This is very much the plastic dimension of the relational forms that are invented in these practices.

Then there is the fact that these shared experiences are expressed in an artistic, tangible form, which is obviously a key difference compared to exclusively political or social participation. However, there is also another distinctive feature: groups are heterogeneous, and the practice only really works when the singularity of each voice in the collective emerges and reflects the group’s complexity. This is a real asset compared with other forms of participation.

Why did you choose the term “cooperative practices”?

Co-creation is a form of participation in which participants, who form a collective, run an artistic project in a cooperative manner and define from the outset what they are going to do together. The artist does not play a specific role in defining the action, whereas in cooperative practices, the artist is at the origin of the project even before the participants’ subjectivities are involved. In reality, however, it is never that simple: the two modes of participation are closely intertwined.

Given that these are processes that unfold over a long period of time, with different levels of involvement, there are phases where the artist is in charge of the project and others where the group acts autonomously, and vice-versa. There is a form of mobility between the different levels of participation.

Hence, I talk about cooperation, which allows the various voices and subjectivities to come to the fore at different times, rather than co-creation, which leaves less room for positions and functions to change and evolve.

How does the recent awareness of more-than-human communities and subjectivities influence cooperative practices?

Let us take the example of “Levain”, a collaborative research project in which I am involved as an artist and which brings together scientists, peasant bakers, craftspeople who do not produce their own wheat, and bakery trainers.

Our group met to identify the impact of the environment and the history of bakery on sourdough biodiversity. We already knew that the sourdough produced by peasants and bakers was biologically rich, and that this richness was fuelled in particular by the tools and hands of the bakers who handled it. This is a truly sympoietic relationship, to use Donna Haraway’s term. The research consists of finding out how far the sourdough feeds to acquire this important microbial diversity.

Fournil La Tit Ferme, 2022 © Marie Preston

In the course of this research, did the question arise of how to gather the voice of the sourdough?

Absolutely. However, before that, there was a whole process of reflection on how to build a common language between scientists, peasants, bakers, and artists, each of whom have their own specific vocabulary. After that, we tried to define how we related to this living entity. We were all aware that it requires special care. However, we soon realised that sourdough also takes care of us, i.e. that without sourdough, the bread we eat would not have the quality it has. Reciprocity – mutual care, as it were – is therefore very important.

Then we realised that we could not make the leaven talk – it cannot actually speak. Instead, we tried to project ourselves: if sourdough were an animal or a plant, what would it be? In answering this question, each of us tells the story of how we see our own sourdough. The examples given reveal very different relationships: domestication for some, cohabitation or friendship for others. Projecting oneself also leads to forms of anthropomorphisation, which in a way reduces the distance between the person and the sourdough, even if this may appear problematic in certain respects.

Finally, there is the question of how one listens and observes. In the animal world, we talk about ethology as the field of zoology that investigates the behaviour of non-human animals, but we can also speak of plant ethology, which in this case involves paying particular attention to how sourdough reacts. This type of listening focuses on the practice of living things, in this case the practice of baking. The scientific work consists of setting up experimental protocols to understand what some bakers know intuitively. In other words, our aim is not to get the leaven to talk, but to actively include it in our research.

Is the growing interest in participative or co-creative practices linked to the need for new imaginaries? In a changing world, what is the role of co-creative practices?

Cooperative artistic practices enable us to tackle societal and political issues in a different way, to open up our imaginations and to do so collectively. This collective act also helps to combat the feelings of anxiety that are generated when one is alone at home worrying about the climate crisis or the extinction of a species, and to become an actor rather than just an onlooker.

What about the interest shown by institutions?

Institutional interest in these practices is quite present in the criticism of cooperative practices, in that they might be said to contribute to legitimise the disengagement of the State from public services.

The associations or art centres that support these practices can offer a response to this question of instrumentalisation that might help minimise or even prevent it by suggesting that the group itself should be in a position to “invent institutionally”.

In other words, we can work on it by coming up with “counter-institutions”. I believe that cooperative artistic practices – because they are constantly reflecting on their own relational modalities – can also act on the structure that allows them to exist, if they have the will to do so.

Image: Bermuda, 2022 © Marie Preston

Public support for participatory practices, judged in ethical rather than aesthetic terms, is often justified in terms of social impact. What are the underlying risks of this approach?

In 2019, we coordinated a book, Cocreation, together with Céline Poulin and Stéphane Airaud, in which we dedicate an entire chapter to the question of evaluating these practices. Just because a project is funded with the aim of having a social impact or to be exclusively artistic does not mean that it should only be assessed through this filter. Of course, artists are going to want to create art, researchers are going to want to find scientific answers, people in civil society are going to want to have fun, make art, or find scientific answers: it is essential to find ways of evaluating these practices with regard to the implications of the people who make up the group, i.e. ultimately, the evaluation takes place downstream and not upstream. Once again, this raises the question not only of the indeterminacy of the project itself, but also the limits of its instrumentalisation.

Given your experience, what do you think are the important questions to ask yourself at the start of a cooperative practice?

Pedagogue Fernand Oury used to say that the first question to ask yourself when you join a group is: “What am I doing here?” Cooperation puts your own vulnerability to the test: are you ready to question your habits, your ways of doing things, to be challenged by the collective and by all the affects that the collective will bring? Are you prepared to let yourself be carried along by what is going to happen? To accept improvisation? To let go of the control you sometimes feel the need to retain when a subject is close to your heart or when you are emotionally involved in the artistic project?

How can one set up a co-creative practice in a community or territory other than one’s own?

I am very interested in reflexive anthropology, i.e. a form of anthropology that questions its own methods of investigation and its relationship with the people it meets, and above all, that incorporates the subjectivity of the researcher. The most important thing, when working in a new place, with people whose practices you do not know, is to listen, observe, be with the people, and be respectful of their differences, ethically and scrupulously.

Finally, you have to get involved and accept contradiction, which goes back to what we said earlier about the questions you need to ask yourself. I also think it is important not to arrive empty-handed: you have to be generous in your involvement and in every way you can.

Bodies of Water

The transition of life from water to land is one of the most significant evolutionary milestones in the history of life on Earth. This transition occurred over millions of years as early aquatic organisms adapted to the challenges and opportunities presented by the terrestrial environment. One of those was the need to conserve water: living beings, in a way, had “to take the sea within them”, and yet, although our bodies are composed mostly of it, biological water actually counts for just 0.0001% of Earth’s total water.

Water is involved in many of the body’s essential functions, including digestion, circulation and temperature regulation. Nevertheless, our bodily fluids, from sweat to pee, saliva and tears, are not just contained within our individual bodies but are part of a more extensive system that includes all life on Earth, blurring the boundaries between our bodies and more-than-human organisms, connecting us to the world around us. Scholars described this idea as hypersea: the fluids that flow through our bodies are connected to the oceans, rivers and other bodies of water that make up the planet and are part of a larger system that connects all living beings together.

Recognising the interconnectedness of all life on Earth and the role that water plays in this interconnected web can help us better understand our place in the world and the importance of working together to protect and preserve this precious element. However, to fully grasp the consequences of this perspective, it is necessary to consider some significant issues addressed by scholar Astrida Neimanis, the theorist of hydrofeminism, in her book Bodies of Water.

One of the main contributions of hydrofeminism to the discussion on bodies of water is the proposal to reject the abstract idea of water to which we are accustomed. Water is usually described as an odourless, tasteless and colourless liquid and is told through a schematic and de-territorialised cycle that does not effectively represent the ever-changing, yet situated, reality of water bodies. Water is mainly interpreted as a neutral resource to be managed and consumed, even though it is a complex and powerful element that affects our identities, communities and relationships. Deep inequalities exist in our current water systems, shaped by social, economic and political structures.

Neimanis shares an example explicitly related to bodily fluids. The Mothers’ Milk project, led by Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook, found that women living on the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation had a 200% greater concentration of PCBs in their breast milk due to the dumping of General Motors’ sludge in nearby pits. Pollutants such as POPs hitch a ride on atmospheric currents and settle in the Arctic, where they concentrate in the food chain and are consumed by Arctic communities. As a result, the breast milk of Inuit women contains two to ten times the amount of organochlorine concentrations compared to samples from women in southern regions. This “body burden” has health risks and affects these lactating bodies’ psychological and spiritual well-being. The dumping of PCBs was a human decision, but the permeability of the ground, the river’s path and the fish’s appetite are caught in these currents, making it a multispecies issue.

Hence, even though we are all in the same storm, we are not all in the same boat. The experience of water is shaped by cultural and social factors, such as gender, race and class, which can affect access to safe water and the ability to participate in water management. The story of Inuit women makes it clear how water, even if it is part of a single planetary cycle, is always embodied, and so are bodies of water with their complex interdependence. While hydrofeminism invites us to reject an individualistic and static perspective, it also reminds us that differences should be recognised and respected. Indeed, it is only in this way that thought can be transformed into action towards more equitable and sustainable relationships with all entities.

Neimanis also approaches the role of water as a gestational element, a metaphor for this life-giving substance’s transformative yet mysterious power. Like the amniotic fluid that surrounds and nurtures a growing animal, water can support and sustain life, nourish and protect, and foster growth and development. In this sense, water can be seen as a symbol of hope and possibility, a source of renewal and regeneration that can help us navigate life’s challenges and transitions. Like a gestational element, water has the power to cleanse, heal and transform. While seeking to find our way in a constantly changing world, we can look to water as an inner source of strength and inspiration, a reminder of life’s resistance and adaptability and the potential that lies within us all.

Image: Edward Burtynsky, Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, Baja, Mexico, 2012. Photo © Edward Burtynsky.

Intimity Among Strangers

Covering nearly 10% of the Earth’s surface and weighing 130.000.000.000.000 tons—more than the entire ocean biomass—they revolutionised how we understand life and evolution. Few would probably bet on this unique yet discrete species: lichens.

Four hundred and ten million years ago, lichens were already there and seem to have contributed, through their erosive capacity, to the formation of the Earth’s soil. The earliest traces of lichens were found in the Rhynie fossil deposit in Scotland, dating back to the Lower Devonian period—that of the earliest stage of landmass colonisation by living beings. Their resilience has been tested in various experiments: they can survive space travel without harm; withstand a dose of radiation twelve thousand times greater than what would be lethal to a human being; survive immersion in liquid nitrogen at -195°C; and live in extremely hot or cold desert areas. Lichens are so resistant they can even live for millennia: an Arctic specimen of “map lichen” has been dated 8,600 years, the world’s oldest discovered living organism.

Lichens have long been considered plants, and even today many interpret them as a sort of moss, but thanks to the technical evolution of microscopes in the 19th century, a new discovery emerged. Lichen was not a single organism, but instead consisted of a system composed of two different living things, a fungus and an alga, united to the point of remaining essentially indistinguishable. Few know that the now familiar word symbiosis was coined precisely to refer to this strange structure of lichen. Today we understand that lichens are not simply formed by a fungus and an alga. There is, in fact, an internal variability of beings involved in the symbiotic mechanism, frequently including other fungi, bacteria and yeasts. We are not dealing with a single living organism but an entire biome.

Symbiosis’ theory was long opposed, as it undermined the taxonomic structure of the entire kingdom of the living as Charles Darwin had described it in On the Origin of Species: a “tree-like” system consisting of progressive branches. The idea that two “branches” (and, moreover, belonging to different kingdoms) could intersect called everything into question. Significantly, the fact that symbiosis functioned as a mutually beneficial cooperation overturned the idea of the evolutionary process as based on competition and conflict.

Symbiosis is far from being a minority condition on our planet: 90% of plants, for example, are characterised by mycorrhiza, a particular type of symbiotic association between a fungus and the roots of a plant. Of these, 80% would not survive if deprived of the association with the fungus. Many mammalian species, including humans, live in symbiosis with their microbiome: a collection of microorganisms that live in the digestive tract and enable the assimilation of nutrients. This is a very ancient and specific symbiotic relationship: in humans, the genetic difference in the microbiome between one person and another is greater even than their cellular genetic difference. Yet the evolutionary success of symbiotic relationships is not limited to these incredible data: it is the basis for the emergence of life as we know it, in a process described by biologist Lynn Margulis as symbiogenesis.

Symbiogenesis posits that the first cells on Earth resulted from symbiotic relationships between bacteria, which developed into the organelles responsible for cellular functioning. Specifically, chloroplasts—the organelles capable of performing photosynthesis—originated from cyanobacteria, while mitochondria—the organelles responsible for cellular metabolism—originated from bacteria capable of metabolising oxygen. Life, it seems, evolved from a series of symbiotic encounters, and despite numerous catastrophic changes in the planet’s geology, atmosphere and ecosystems across deep time, has been flowing uninterruptedly for almost four billion years.

Several scientists tend to interpret symbiosis in lichens as a form of parasitism on the part of the fungus because it would gain more from the relationship than the other participants. To which naturalist David George Haskell, in his book The Forest Unseen, replies, “Like a farmer tending her apple trees and her field of corn, a lichen is a melding of lives. Once individuality dissolves, the scorecard of victors and victims makes little sense. Is corn oppressed? Does the farmer’s dependence on corn make her a victim? These questions are premised on a separation that does not exist.” Multi-species cooperation is the basis of life on our planet. From lichens to single-celled organisms to our daily lives, biology tells of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option. Lynn Margulis described symbiosis as a form of “intimacy among strangers”: what lies at the core of life, evolution and adaptation.

A Sub-Optimal World

Olivier Hamant is a transdisciplinary biologist and researcher at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and the Environment (INRAE) in Lyon, and is engaged in socio-ecological education projects at the Michel Serres institute.

His book “La Troisième Voie du Vivant” envisions a “sub-optimal” future to survive the environmental crisis: in this interview, he promotes the values of slowness, inefficiency and robustness, and invites us to embrace a certain degree of chaos.

Authors and philosophers have always been inspired by the observation of nature to speculate about reality and society, but often with an instrumental approach. You too are inspired by nature, but from your point of view as a biologist, you come to some conclusions that challenge our prejudices on how nature works. How did your questioning begin?

During my PhD I worked on plant molecular biology, looking at genetic control and information. It was a clear example of an industrial framework transposed to biology: we used organigrams, we drew cascades of genes, we discussed “lines of defence,” “metabolic channelling” … Such semantics implied that life is like a machine. When I finished my PhD, I decided to try out a more integrated and interdisciplinary approach to get a more systemic view of biology. This confirmed that what I thought I knew was wrong: I’d been polluted by the concept of living beings as machines, and that’s where I started to deviate.

The book is, in fact, a real lesson in “unlearning,” as you overturn some contemporary concepts that may seem positive but ultimately aren’t, such as “optimisation.”

Optimisation is the archetype of reductionism: to optimise, you first need to reduce a given problem in order to solve it. When we solve small problems, we usually create other issues elsewhere. Take the Suez Canal for example: that’s a form of optimisation, of sea transport here, that makes us very vulnerable. A single boat gets stuck across the canal, and that’s it, you can’t send anything between Asia and Europe.

What about “efficiency”?

Photosynthesis is probably the most important metabolic process on Earth: it has existed for 3.8 billion years, and it’s the root of all biomass and civilisation. The “performance” of photosynthesis is usually less than 1%: plants waste more than 99% of solar energy. They’re really, really inefficient. Plants are green because they don’t absorb all the light; they absorb the red and blue sections of the light spectrum (the edge of the spectrum) and reflect the green part. Why do they waste so much energy? It’s now recognised that this is a response to light fluctuation. Light isn’t stable and capturing the red and blue sections allows plants to face such fluctuations. Plants manage variability before efficiency. They build robustness against performance.

Today, we see that the world is unstable, and it will become more so in the future: we shouldn’t be focusing on efficiency but on robustness. When we look for inspiration from biology, we often focus on circularity and cooperation. It’s a good start, but if we overlook robustness, it won’t work. For instance, if we come up with a form of efficient circularity, we won’t have enough wiggle room for extreme events, and we’ll exhaust the available resources anyway. If we make cooperation efficient, the win-win result will be counterproductive, and some will be left behind. Thus, robustness is the most important principle because it makes circularity and cooperation operational.

The most substantial criticism in your book concerns performance, drawing a parallel between violence against the environment and burnout.

Performance generates burnout—it’s a typical effect. Burnout applies to a person or an ecosystem. The path towards burnout is sufficient to condemn “efficiency at all costs,” but performance is also counterproductive in many other ways. A typical example is sports competitions: you want to be number one, you’ll do anything, including doping or cheating. That has nothing to do with sport and it’s detrimental to your health and career.

You also take concepts we interpret negatively and explain how they are actually positive, such as slowness or hesitation…

Slowness and hesitation are the keys to competence, as might be illustrated by stem cells. Biologists have focused on these cells for a long time because they’re extraordinary: they can renew all kinds of tissues. For a long time, we thought this was all controlled by a tidy organigram. It turns out that one of the key elements is that they’re slow: they hesitate all the time, and because they hesitate, they can do anything. Delays give some breathing space. I would actually go one step further: slowness is an essential lever for transformation. To change, you first need to stop. It’s like being in a car at a crossroads; if you want to change direction, you need to stop, indicate and turn. If you don’t stop, you won’t change.

Change is the keyword here. Hard science, numbers and prediction systems often lack the ability to consider contingencies or change, giving us the illusion that we have some form of control over reality.

Thankfully, we’ve made progress and now we use numbers to understand the unpredictability of the world (instead of using numbers to control it). For instance, in the lab, we’re working on the reproducibility of the shapes of organs. In a tulip field, all flowers look alike. You could think of an IKEA-like process: building things in the same way also makes them replicable. But this isn’t the case for living systems: when a flower emerges, some cells divide, others die, molecules come and go… Basically, it’s a mess. In the end, the miracle is that you get a flower with the same shape, colour and size as the neighbouring one. We showed that the flower uses and even promotes all kinds of erratic behaviours, precisely because they provide valuable information, to reach that reproducible shape. Once again, they build robustness against performance.

So, a certain degree of chaos should be embraced?

Sociologist Gilles Armani once told me a story about how to deal with impetuous rivers. The Rhône has all these swirls: if you don’t know how to swim through them, you might get trapped and drown. When people were used to living with rivers, if caught in the water flow, they wouldn’t fight it: they’d take in some air, let themselves be taken down by the swirl and the river would then let them out somewhere else, until they reached the shore. In a fluctuating world, the aim is no longer reaching one’s destination as quickly as possible, but rather viability, something which should be based not against, but on turbulence.

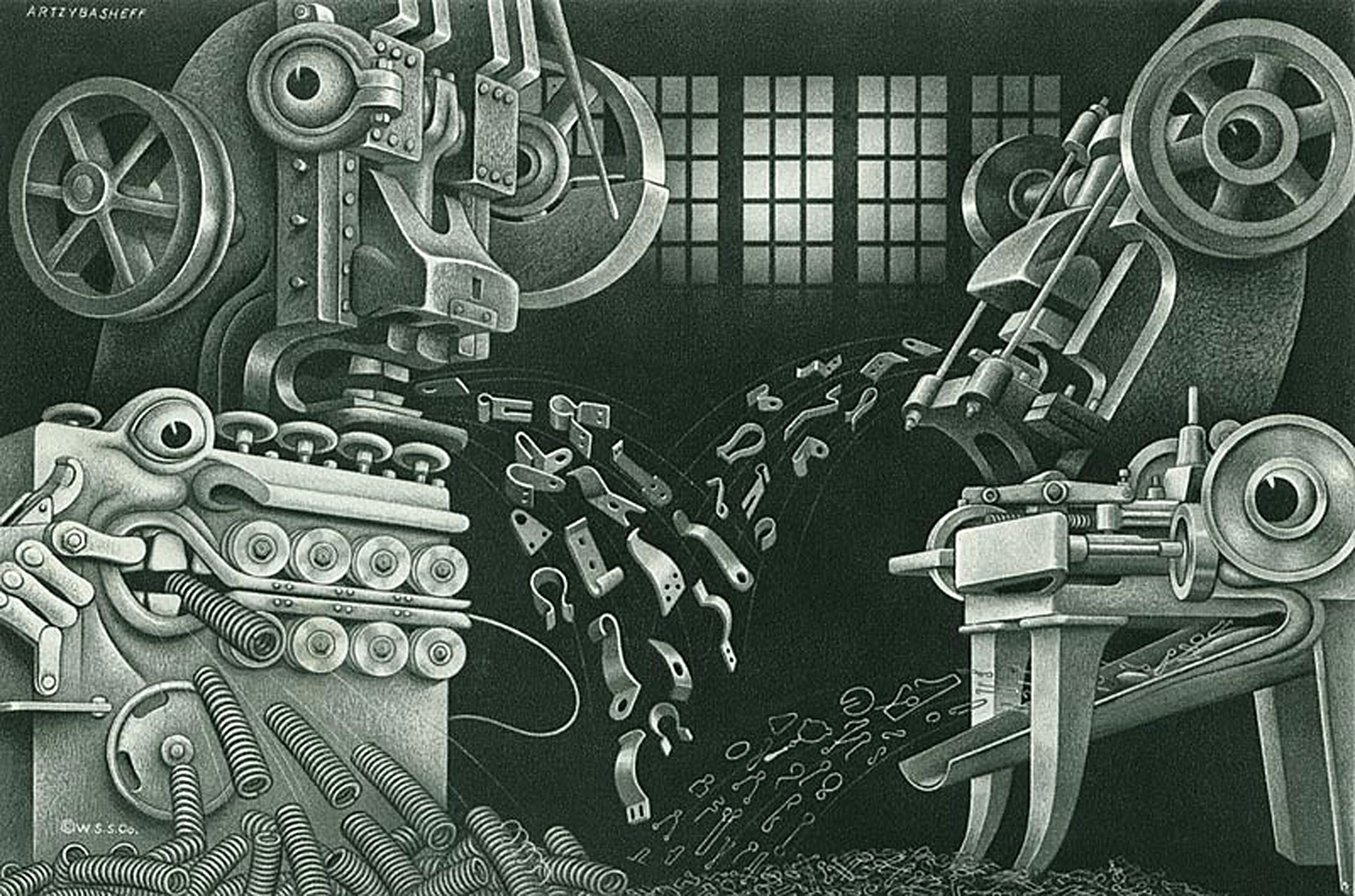

Image: Boris Artzybasheff.

Learning from mould

Reading

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Learning from mould

Physarum polycephalum is a bizarre organism of the slime mould type. It consists of a membrane within which several nuclei float, which is why it is considered an “acellular” being—neither monocellular nor multicellular. Despite its simple structure, it has some outstanding features: Physarum polycephalum can solve complex problems and move through space by expanding into “tentacles,” making it an exciting subject for scientific experiments.

The travelling salesman problem is the best known: it’s a computational problem that aims to optimise travel in a web of possible paths. Using a map, scientists at Hokkaido University placed a flake of oat, on which Physarum feeds, on the main junctions of Tokyo’s public transportation system. Left free to move around the map, Physarum expanded its tentacles, which, to the general amazement, quickly reproduced the actual public transport routes. The mechanism is very efficient: the tentacles stretch out in search of food; if they do not find any, they secrete a substance that will signal not to pursue that same route.

We are used to thinking of intelligence as embodied, centralised, and representation-based: Physarum teaches us that this is not always the case and that even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating.

Putting Off the Catastrophe

If the end is nigh, why aren’t we managing to take global warming seriously? How can we overcome the apathy of our eternal present? The following article is taken from MEDUSA, an Italian newsletter that talks about climate and cultural changes. Edited by Matteo De Giuli and Nicolò Porcelluzzi in collaboration with NOT, it comes out every second Wednesday and you can register for it here. In 2021, MEDUSA also became a book.

There is no alternative was one of Margaret Thatcher’s slogans: wellbeing, services, economic growth… are goals achievable exclusively by doing things the free market way. 40 years on, in a world built on those very election promises, There is no alternative sounds more like a bleak statement of fact, a maxim curbing our collective imagination: there is no alternative to the system we’re living in. Even when we’re hit by crisis, in times of unrest, exploitation and inequality, the state of affairs finds us more or less defenceless. There’s no escape – or we can’t see it: our room for manoeuvre has been fenced off.

Why can’t we take global warming seriously? Because it’s one of those complex systems that operate, as Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams affirm in their Inventing the Future, “on temporal and spatial scales that go well beyond the bare perceptual capacities of the individual” and whose effects “are so widespread that it’s impossible to exactly collocate our experience within their context”. In short, the climate problem is also the result of a cognitive problem. We are lost in the corridors of a vast and complex building in which we see no direct and immediate reaction to anything we do and have no clear moral compass to help us find our way.

It was to pursue these issues further that I decided to read What We Think About When We Try Not to Think About Global Warming (hereafter WWTAWWTNTAGW) by Norwegian psychologist and economist Per Espen Stoknes, a book I’d been putting off reading for some time for a series of reasons that turned out to be only partially valid. First of all, there was my vaguely scientist prejudice: despite being interested in the issue, I find that the back cover of WWTAWWTNTAGW sounds more like front flap blurb for some self-help publication rather than for a serious work of popular science. I quote: “Stoknes shows how to retell the story of climate change and at the same time create positive, meaningful actions that can be supported even by negationists”. Then there was the title, WWTAWWTNTAGW, a cumbersome paraphrase of a title that is already, in itself, the most ferociously paraphrased in the history of world literature. And lastly — still on the surface only – there was the spectre of another book by Per Espen Stoknes, published in 2009, the mere cover of which I continue to find insurmountably cringeful: Money & Soul: A New Balance Between Finance and Feelings.

Laying aside, for the moment at least, the prejudices that kept me away from WWTAWWTNTAGW, I discovered a light-handed book that raises various interesting points. In short: why does climate change, our future, interest us so little? Why do we see it as such an abstract and remote problem? What are the cognitive barriers that are sedating, tranquillizing and preventing us from having even the slightest real fear for the fate of the planet? Stoknes identifies five, which can be summed up more or less as follows:

Distance. The climate problem is still remote for many of us, from various points of view. Floods, droughts, bushfires are increasingly frequent but still affect only a small part of the planet. The bigger impacts are still far off in time, a century or more.

Doom. Climate change is spoken of as an unavoidable disaster that will cause losses, costs and sacrifices: it is human instinct to avoid such matters. We are predictably averse to grief. Lack of practical solutions on offer exacerbates feelings of impotence, while messages of catastrophe backfire. We’ve been told that “the end is nigh” so many times that it no longer worries us.

Dissonance. When what we know (using fossil fuel energy contributes to global warming) comes into conflict with what we’re forced to do or what we end up doing anyway (driving, flying, eating beef), we feel cognitive dissonance. To shake this off, we are driven to challenge or underestimate the things we are sure about (facts) in order to be able to go about our daily lives with greater ease.

Denial. When we deny, ignore or avoid acknowledging certain disturbing facts that we know to be “true” about climate change, we are shielding ourselves against the fear and feelings of guilt that they generate, against attacks on our lifestyle. Denial is a self-defence mechanism and is different from ignorance, stupidity or lack of information.

Identity. We filter news through our personal and cultural identities. We look for information that endorses values and presuppositions already inside our minds. Cultural identity overwrites facts. If new information requires us to change ourselves, we probably won’t accept it. We balk at calls to change our personal identities.

There are obviously hundreds of other reasons why we still hold back from a strategy to mitigate climate change: economic interests, the slowness of diplomacy, conflicting development models, the United States, India, sheer egoism, “great derangement” and all the other things we’ve come to know so well over the years. But Per Espen Stoknes empirically suggests a way forward. Catastrophism and alarmism don’t work. We need to find a different tone to dispel the apathy of our eternal present.

Image: The Grosser Aletsch, 1900 Photoglob Wehrli © Zentralbibliothek Zürich, Graphische Sammlung und Fotoarchiv/ 2021 Fabiano Ventura – © Associazione Macromicro.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School is a project that focuses on survival, the commons, and hopes and strategies for addressing climate change and the Anthropocene. The video, crafted by the students at College Sismondi under the guidance of Carlos Tapia, documents the co-creative process led by artist Maria Lucia Cruz Correia, which resulted in the construction of a “floating island” on the waters of Lake Geneva.

press

Permaculture, the ecological model to reinvent culture

L’Hebdo du quotidien de l’art, 02/09/2024

A floating school to rethink our relationship with the climate and the environment

RTS, 11/29/2023

An initiative to accompany our society in its transformation

Kunstbulletin 5/2023

least, an association that wants to save the planet through the arts

Forum, RTS, 04/26/2023

«Common Dreams», a floating platform in Geneva

Le Temps, 04/20/2023

A platform on the waves for a better life

Le Temps, 04/20/2023

The association least dreams of saving the planet through the arts

Tribune de Genève, 03/22/2023