laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

Faire commun

Since 2023, least has been involved in Faire commun: Évaluation Collective et Sensible des Communs de Rigot (ECSCo), a transdisciplinary research project launched by HES-SO, in collaboration with HEPIA, HEAD – Genève, and the OCAN (Cantonal Office of Agriculture and Nature).

The ‘commons’ refers to a resource – here the Parc Rigot area, its water, biodiversity and plants –, managed collectively by a community. The aim of this research is to evaluate the commons of the park, develop the long-term management of the site by the user community (IHEID, Collège Sismondi, CHC collective accommodation centre, Rigot Hospice général, etc.) and raise awareness of the benefits of interspecies cohabitation.

Users are invited to get directly involved in the decision-making process and the creation of adaptable tools, in particular through participatory workshops organised over the months.

In addition, the project seeks to develop critical methodological avenues for disseminating these experiments to other areas and neighbourhoods in the Greater Geneva area, with the aim of encouraging the development of a thriving, sustainable city.

what we’ve done

Each entity involved - HEPIA, HEAD - Geneva and least - organised a number of ‘activations’ (surveys, workshops, artistic performances, etc.) to reveal different aspects of the park’s commons, and invited the communities around Parc Rigot to participate, thereby strengthening their interconnection and their involvement in the evaluation process.

The Commun’sol activation carried out by artist Thierry Boutonnier and least aimed to assess, in a sensitive and embodied way, the underground life of the park. During a group workshop, an organic cotton tablecloth was cut up and buried in various places in the park, so that once the pieces of tablecloth had been recovered, the traces of the earth’s bioactivity could be observed.

On 21 November, we hosted a workshop by Alexandre Monnin which aimed to foster opportunities for people to carry out research and share knowledge. Using the Parc Rigot model as a basis for rethinking the collective governance of the commons, we took a closer look at the transformations of professions with a view to sketching out the future of artistic and cultural practices.

what’s next

With the assistance of experts and researchers, we are analyzing the environmental and anthropological context of Parc Rigot, focusing on past actions of support, protection, and maintenance of the park’s commons. We are developing the project’s vocabulary with particular attention to including the more-than-human dimension. Meanwhile, the participatory activities organized by the various entities involved in the project continue.

what’s next

The activations and experiences will be documented in a series of gazettes. These interdisciplinary publications will track the progress of the project and deepen both theoretical and practical exploration of the commons and their long-term management. This work will enable us to select, question, and expand the meaning of key concepts such as the subsoil, plant rhythms, interhuman and interspecies coexistence, and communal resources.

newsletter

Stay up to date about our latest activities, articles, inspirations and much more!

transdisciplinary team

Microsillons – artists collective and professor HEAD, Geneva

Laurence Crémel – professor HEPIA, Geneva

Maëlle Proust – Scientific Collaborator HES in Landscape Architecture – HEPIA

Charlotte Chowney – Scientific Assistant HEPIA, Geneva

Tiphaine Bussy – Landscape Architect, Project Manager OCAN (Office cantonal de l’agriculture et de la nature), Geneva

Baptiste Bonnard – Illustrator

Fichtre – Illustrator

Roman Alonso Gomez – Architect (ALICE – Atelier de la conception de l’espace, EPFL)

Alexandre Monnin – researcher

artistic team

Thierry Boutonnier – arborist artist

Eva Habasque – arborist artist

Yayan Liu – arborist artist

media

The Nest

Reading

A poetic reflection by Gaston Bachelard on the nest as a symbol of intimacy, refuge, and imagined worlds.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Everything Flows

Reading

Life relies on a delicate synchronization between the rhythms of living beings and the cycles of the Earth.

Faire commun

Vivre le Rhône

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Living Soil

Reading

Although we walk on it every day, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

Fences and Power

Reading

The fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

Arpentage

Faire commun

d'un champ à l'autre / von Feld zu Feld

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Autumn in the Garden

Reading

“We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn”.

CROSS FRUIT (ex Verger de Rue)

Faire commun

Arpentage

How happy is the little stone

Reading

Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life.

Peau Pierre

Arpentage

Faire commun

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Ô noble Green

Reading

The «Ignota Lingua» by Hildegarde of Bingen.

CROSS FRUIT

Common Dreams

Faire commun

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Reading

Yves Citton discusses commons, negative commons, and sub-commons with us.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Experiencing the Landscape

Reading

The complexity of the term ‘landscape’ can best be understood through the concept of ‘experience’.

Vivre le Rhône

Faire commun

Arpentage

CROSS FRUIT

Se rencontrer sur le seuil

Listenting to the Sourdough

Reading

An interview with the artist and scholar Marie Preston on cooperative practice and including the more-than-human.

Common Dreams Panarea: Flotation School

Faire commun

Wild Bread

Reading

An essay about the experience of hunger in Europe in the modern age.

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

Bodies of Water

Reading

Embracing hydrofeminism.

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

Intimity Among Strangers

Reading

Lichens tell of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option

Common Dreams

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

A Sub-Optimal World

Reading

An interview with Olivier Hamant, author of the book “La troisième voie du vivant”.

Common Dreams

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

The Nest

Here is an excerpt from The Poetics of Space by 20th-century French philosopher Gaston Bachelard. In this work, Bachelard explores spaces of human intimacy – houses, drawers, nooks, nests – not as physical objects, but as places imbued with life and imagination. The passage featured is a poetic and thoughtful meditation on the nest, viewed as a vital refuge, the centre of a universe that is both real and imagined.

It is the living nest, however, that might introduce a phenomenology of the real nest, the nest found in nature, which becomes, for a fleeting moment (and the word is not too grand), the centre of a universe, the marker of a cosmic situation. I gently lift a branch, the bird is there, brooding on its eggs. It does not fly away. It only trembles, slightly. I tremble at making it tremble. I fear that the nesting bird knows I am a man, that being who has lost the trust of birds. I remain still. Slowly – so I imagine – the bird’s fear and my fear of causing fear subside. I breathe more easily. I let the branch fall back. I’ll return tomorrow. But today, I carry a quiet joy: the birds have built a nest in my garden.

And the next day, when I return, walking even more softly, I see, at the bottom of the nest, eight eggs of a pale pinkish white. My God! How small they are! How tiny a hedge bird’s egg is!

There is the living nest, the inhabited nest. The nest is the bird’s home. I’ve long known this, it’s long been said to me. It’s such an old truth that I hesitate to repeat it, even to myself. And yet I have just relived it. I recall, with a clear and simple memory, those rare moments in life when I have discovered a living nest. How few and precious are such true memories in a lifetime!

I now fully understand Toussenel’s words:

“The memory of the first bird’s nest I found on my own has remained more deeply etched in my mind than that of the first Latin prize I won at school. It was a lovely greenfinch’s nest with four grey-pink eggs, traced with red lines like a symbolic map. I was struck on the spot by an unspeakable joy that rooted me there for over an hour. It was my calling that chance revealed to me that day.”

What a beautiful passage for those of us seeking the sources of our earliest fascinations! When we resonate, even from afar, with such a shock, we better understand how Toussenel could integrate, in both life and work, the harmonic philosophy of Fourier, adding to the bird’s life an emblematic dimension, a universe of meaning.

And even in ordinary life, for someone who lives among woods and fields, the discovery of a nest is always a fresh emotion. Fernand Lequenne, the plant lover, walking with his wife Mathilde, spots a warbler’s nest in a blackthorn bush:

“Mathilde kneels down, reaches out a finger, brushes the fine moss, holds her hand there, suspended…

Suddenly, I shudder.

I’ve just discovered the feminine meaning of the nest, perched in the fork of two branches. The bush takes on such human significance that I cry:

– Don’t touch it, whatever you do, don’t touch it!”

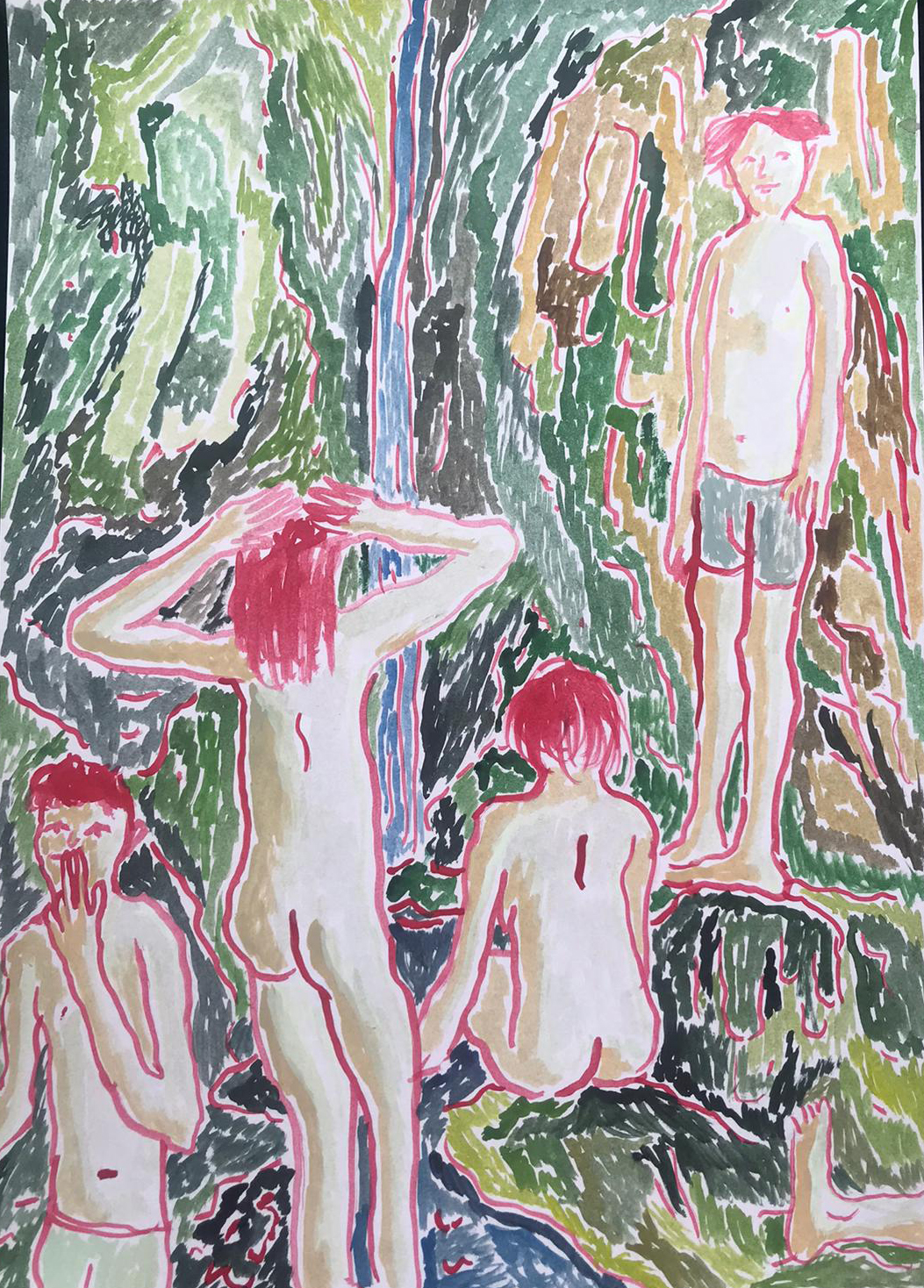

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Toussenel’s shock, Lequenne’s shudder, both carry the unmistakable mark of sincerity. We echo them in our reading, since it is often in books that we experience the thrill of “discovering a nest.” Let us then continue our search for nests in literature.

Here is an example where a writer intensifies the nest’s role as home. We have borrowed it from Henry David Thoreau. In his writing, the entire tree becomes, for the bird, the vestibule of its nest. Already, the tree that shelters a nest partakes in the mystery of the nest. For the bird, the tree is a refuge.

Thoreau shows us the woodpecker making a home of the whole tree. He compares this act of possession to the joyful return of a family moving back into a long-abandoned house: “Just as when a neighbouring family, after a long absence, returns to their empty home, I hear the joyful sounds of voices, the laughter of children, and see smoke rising from the kitchen. The doors are flung wide open. The children race through the hall, shouting. So too, the woodpecker darts through the maze of branches, drills a window here, bursts out chattering, dives elsewhere, ventilates the home. It calls out from top to bottom, prepares its dwelling… and claims it.”

Thoreau gives us, all at once, the nest and the house unfolding. Isn’t it striking how his text breathes in both directions of the metaphor: the joyful house becomes a vibrant nest – and the woodpecker’s trust, hidden in its tree-nest, becomes the confident claiming of a home.

Here, we go beyond mere comparison or allegory. The “proprietor” woodpecker, appearing at the tree’s window, singing from its balcony, a critical mind might call this an “exaggeration.” But the poetic soul will be grateful to Thoreau for expanding the image, giving us a nest that reaches the size of a tree.

A tree becomes a nest the moment a great dreamer hides in its branches. In Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, Chateaubriand shares such a memory: “I had built myself a perch, like a nest, in one of those willows: there, suspended between earth and sky, I would spend hours with the warblers.”

Indeed, when a tree in the garden becomes home to a bird, it becomes dearer to us. However hidden, however silent the green-clad woodpecker may be among the leaves, it becomes familiar. The woodpecker is no quiet tenant. And it’s not when it sings that we think of it, but when it works. All along the tree trunk, its beak strikes the wood with resonant blows. It often vanishes, but its sound remains. It’s a labourer of the garden.

And so, the woodpecker has entered my sound-world. I’ve turned it into a comforting image. When a neighbour in my Paris flat hammers nails into the wall late into the evening, I “naturalise” the noise. True to my method of making peace with anything that disturbs me, I imagine myself back in my house in Dijon, and I say to myself: “That’s just my woodpecker, working away in my acacia tree.”

Everything Flows

As part of Faire commun – a shared ecology project in Parc Rigot – least invites you to reflect on the rhythms that flow through living beings, places and time itself. “Faire commun” also means “making time together”: exploring how our lives align – or fall out of step – with the cycles that surround us. This text invites readers to attune to the world’s many pulses, imagining new forms of sensitive coexistence.

At Parc Rigot, students, researchers and artists came together to resonate with the land – an interdisciplinary and sensory exploration aimed at revealing the unique rhythms of the landscape, its lifeforms and its uses. By observing the park’s centuries-old oaks, its passers-by and its pond, they highlighted how each element vibrates at its own tempo – sometimes steady, sometimes chaotic – composing a shared, living score.

The word “rhythm” comes from the Greek verb rhéô, meaning “to flow”. In Greek philosophy, panta rhei (“everything flows”) captures the thought of Heraclitus of Ephesus, philosopher of perpetual change: all is in constant transformation, like a river whose waters move constantly, so much so that “one can never step into the same water twice” …

Water, indeed, is at the heart of our first experience of rhythm. Even before birth, we perceive sound through amniotic fluid: heartbeats, breath, blood flow. Only low, rhythmic sounds travel through this liquid medium. After birth, part of this water remains in us: the inner ear, still filled with fluid, senses the world’s vibrations. This original water holds a deep memory of rhythm and time within us. Perhaps that is why Rigot’s pond, nestled at the base of the park, acts as a sensory magnet: it draws the eye, attracts wildlife and becomes a focal point where human and non-human rhythms converge across the day.

Humanity has long sought to measure time. One of the earliest known instruments is a water clock (clepsydra) from the 14th century BCE, discovered in the Karnak Temple in Egypt. Two vessels, connected by a small opening, allowed time’s flow to be measured steadily. At Rigot, the oaks planted on the western side play a similar role: silent timekeepers, inscribing memory into their bark year after year.

In soundscapes little touched by human activity, most sounds follow predictable rhythms. Birdsong, the rustle of wind in leaves, the soft lapping of water – these recurring motifs are registered by living beings as familiar and non-threatening. Such regularity soothes and stabilises the soul. In contrast, abrupt noises – construction, crowds, traffic – disrupt sensory balance, triggering alarm. Auditory rhythm is thus a key element of perceptual stability.

Rhythm is essential to how every species hears. Neurons in the ear and brain activate only when sound frequencies align with a reference rhythm. In the 1960s, Hungarian researcher Péter Szőke slowed down birdsong to reveal its hidden complexity, unheard by the human ear. This attention to the invisible and the subtle informs the sensory work carried out in Parc Rigot: to listen, to slow down, to observe what often slips beneath the surface of perception.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

For living beings, time unfolds on three levels: internal rhythm, synchronisation with environmental cycles and coordination with others. Internal rhythm is fine-tuned by external signals – zeitgebers (“time-givers”) – such as light, temperature and seasons. For migratory birds, the memory of thawing snow, the length of day and the behaviour of other species help determine when to depart for breeding grounds.

Time, then, is not solely personal, it is also social. In a beehive, nurse bees maintain a constant internal rhythm, while foragers adjust to the timing of flower openings. The coordination of these internal clocks generates a shared rhythm, or a collective time.

Human societies, too, maintain diverse and complex relationships with time. In many Indigenous cultures, time is tied to local rhythms of land, animals and landscapes. Among Sámi reindeer herders, for instance, the concept of jahkodat holds that each year is unique: migration depends on the snow thawing, pasture health and other shifting factors. “One year is not the sister of the next”, a Sámi proverb says: each cycle demands careful attention and constant adaptation.

Today, globalisation has dulled this seasonal sensitivity. Yet seasonality is not universal. Some regions know four seasons; others alternate between wet and dry. In Nagori, Ryoko Sekiguchi notes that Japan traditionally divides the year into 24 seasons, or even 72 micro-seasons. This refined sense of time shapes language itself, with words and haikus linked to precise moments, weaving culture, climate and expression together.

But so-called “objective” time is also a human invention. In Austerlitz, W.G. Sebald reminds us that while time is tied to the stars, it ultimately rests on convention. Even the solar day varies; to stabilise our clocks, we invented a “mean sun” – a fictional body whose steady motion serves as a reference.

The standardisation of time intensified in the 19th century with the advent of railways. To coordinate schedules, time zones were imposed, overriding the diversity of local times. The world entered an era of strict synchronisation, a standardisation that now coexists with the ecological and temporal dissonance we face.

For non-humans, life depends on a fine attunement between living rhythms and Earth’s cycles. Climate change is unsettling these balances. At Rigot, as elsewhere, seasons shift, temperatures rise, blooms and migrations fall out of sync, disrupting biological clocks. This breakdown threatens the reproduction, food sources and survival of many species. When life’s rhythms fall out of step with Earth’s cycles, the very balance of life begins to waver.

In the face of growing dissonance between human time and living time, Faire commun calls for a sensitive reorientation: to slow down, to listen, to live together. Parc Rigot becomes a shared learning ground, where we can explore new ways of inhabiting time, neither linear or productivist, but rather cyclical, porous, attuned to what grows, changes or disappears. By reconciling Earth’s many temporalities, this project sketches the outline of an inhabitable future.

Living Soil

Although we walk on it every day and it is essential to our food security, we rarely consider the importance of soil in our lives. What crucial roles does soil play in maintaining the balance of ecosystems? How can we protect it? And how can artistic practices help?

Below is an interview with Karine Gondret, a trained soil scientist and geomatician, HES-SO research associate and lecturer at the Geneva School of Landscape, Engineering and Architecture (HEPIA). Her research focuses on soil quality assessment and mapping.

What is pedology?

A branch of soil science, pedology focuses on the study of soils, i.e. the interactions between living organisms, minerals, water, and air that take place beneath our feet. In pedology, we examine everything that lies between the surface and the first, purely mineral layer, i.e. around 1.50 m deep in our latitudes. Beyond that, when only minerals remain, we enter the field of geology. The role of the pedologist is also to map the soil.

What is meant by good quality soil?

Broadly speaking, good quality soil is soil that is capable of performing the functions necessary for the survival of all living organisms and their environment. Several functions are very important, beyond the most obvious, that of food or biomass production. Soil infiltrates, purifies, and stores water, and recycles nutrients and organic matter. There is also the genetic reserve function, which is still seldom studied. Penicillin, for example, was discovered in the soil. So it’s crucial to protect our soils.

What parameters need to be taken into account to assess the quality of a soil according to its functions?

In general, the higher the organic content of soil, the better it is able to perform its functions. By organic, we mean all living things (earthworms, micro-organisms, bacteria, etc.) and all carbon-rich compounds derived from living things (corpses, excrement, roots, dead leaves, compost, root and bacterial exudates, etc.). Functioning soil is living soil, and much more!

There are several other essential parameters, such as soil depth, pH, texture, porosity, etc. Depending on the function, certain parameters will be more or less important. For example, the function of supporting human infrastructure (roads, buildings, etc.) will inevitably be detrimental to the biomass production function. That’s why politicians have to make choices about the functions they want to protect.

Why is the presence of organic matter in soils important?

Organic matter is the basic food source for the soil’s fauna and micro-organisms. It is continually broken down by soil life into nutrients that are accessible to plants via soil water. Organic matter also improves soil porosity. Porosity is essential for the proper development of life, as it allows nutrient-rich water, air, and roots to circulate. Without this porosity, exchanges are much less effective, and as a result, its functions are much less effective.

In addition, organic matter is capable of increasing the soil’s capacity to store water and of mitigating flooding in towns downstream. It can also retain nutrients and pollutants through its electrical properties. Finally, organic matter that is stabilised in the soil contains around 60% of carbon, and the more it increases in the soil, the more we limit global warming, because all the carbon that is not stored in the soil goes into the atmosphere in the form of CO2.

We’ve talked about what good soil is for humans, but what about the “more than human” world?

As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), soil performs functions that are essential to humankind. In truth, these functions are essential to the proper functioning of ecosystems, and humans simply benefit from them. For example, many pollinators spend part of their life cycle in the soil. These pollinators make it possible to obtain fruit and feed wildlife, which is beneficial for natural environments. But this fruit also benefits humans within agricultural and economic infrastructures, when it is sold. Humans and the environment are deeply interconnected, although we tend to forget this. Finally, compared to about fifty years ago, the organic matter content in most agricultural soils has halved. This means that these soils are becoming increasingly less effective at performing the functions they provide for us.

Images: Thierry Boutonnier, Comm’un sol, 2024. Photo: ©Eva Habasque.

As part of the Faire Commun research project, artist Thierry Boutonnier devised a method for sensitively assessing the quality of the soil in Parc Rigot. He organised a picnic on a long organic cotton tablecloth, which was then cut into pieces and buried in different areas of the park. After a few months, the tablecloth was dug up, and the amount of fabric consumed thanks to the soil’s bioactivity provided concrete information about its characteristics. What did you observe?

We haven’t yet finished carrying out the analyses in Parc Rigot, but we’ve observed the soil’s capacity to degrade organic matter through this experiment. In the soil, micro-organisms release enzymes that degrade organic matter (here the cotton tablecloth). We also observed that these micro-organisms were not all equally active: in some areas of the park, the organic matter was broken down very efficiently, while in other areas, the process was much slower. This means that in these areas, there are fewer nutrients available for the plants that grow.

People often don’t realise that there is diversity of soils, even in small areas. In the city, as in Parc Rigot, this diversity is even more marked because humans have had such a strong impact on the soil. There have been many interventions – areas have been completely renatured, others stripped, or artificially added – and this has led to a juxtaposition of very different soils. The challenge is to identify the areas that really work, and protect them.

Is it possible to improve soil quality?

When soil doesn’t have the necessary quality for a given function, we can intervene to improve it, for example by adding organic matter or by decompacting it (in compliance with the OSol ordinance in Switzerland). Nevertheless, soil quality only improves very slowly; sometimes it takes several human generations, sometimes improvement is impossible. Soil is a non-renewable resource, as it takes a very long time to create: it is said to increase by an average of 0.05 millimetres per year. In very steep areas, it even becomes thinner and thinner.

It can also deteriorate rapidly. It looks solid and is thought to be immutable, but nothing could be further from the truth. Even when we’re trying to improve its quality, we have to be very careful, because every intervention on the soil leads to its deterioration. It’s a delicate process that doesn’t always work – we’re still experimenting.

Soil is at the intersection of physics, biology, and chemistry. It’s a complex world, and by no means do we know everything about it. So it’s all the more important to protect it, because it’s where all plant nutrients are found, and as they develop, they form the basis of the diet of all mammals. The soil is truly the place where life is created.

Fences and Power

“We pray your grace that no lord of no manor shall common upon the common.

We pray that all freeholders and copyholders may take the profits of all commons, and there to common, and the lords not to common nor take profits of the same.

We pray that Rivers may be free and common to all men for fishing and passage.

We pray that it be not lawful to the lords of any manor to purchase lands freely, (i.e. that are freehold), and to let them out again by copy or court roll to their great advancement, and to the undoing of your poor subjects.”

The date is 6 July 1549. The peasants of Wymondham, a small town in Norfolk, England, have risen in rebellion. They are marching across the fields to cut down the hedges and fences of private farms and pastures, including the estate of Robert Kett, who surprisingly joins the protests, giving his name to the rebellion. As they march, they are joined by farm workers and craftspeople from many other towns and villages. On 12 July, 16,000 insurgents camp at Mousehold Heath, near Norwich, and draw up a list of demands addressed to the King, including those mentioned above. They will hold out until the end of August, when more than 3,500 insurgents will be massacred and their leaders tortured and beheaded. But what provoked this insurrection? And why was the repression so bloody?

Kett’s Rebellion was a reaction to the hardships inflicted by the extensive enclosures of common lands. These lands, which were of great economic and social importance, were managed according to rules and boundaries established by the communities themselves, guaranteeing a balance between their members. The plots were used for grazing, gathering wood and wild plants, haymaking, fishing, or simple passage, and even included shared farmland, where peasants each cultivated small portions of the collective land. The common land system thus contributed to the subsistence of the communities and, in particular, the most disadvantaged.

With enclosures, common land was reorganised to create large, unified fields, demarcated by hedges, walls, or enclosures, and reserved for the exclusive use of large landowners or their tenants. This gradual process of land appropriation was not exclusive to England but was a large-scale phenomenon that spread in various forms throughout Europe (and even more violently in its colonies) from the 15th century onwards. This is the phenomenon that Karl Marx describes in Das Capital as “primitive accumulation”: agricultural workers, deprived of their means of production (land), are forced to work for wages, possessing nothing other than their labour power. This was one of the factors that led to the emergence of capitalism, a process involving violence, expropriation, and the breaking of traditional social ties.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

Another significant aspect of enclosures is their impact on the role of women. Until the Middle Ages, a subsistence economy prevailed in Europe, in which productive work (such as tilling the fields) and reproductive work (such as caring for the family) had equal value. With the transition to a market economy, only work that produced goods was considered worthy of remuneration, while the reproduction of labour power was deemed to have no economic value. What’s more, as we have shown, the loss of use rights over common land particularly affected already-discriminated groups such as women, who found in this land not only a means of subsistence, but also a space for relationships, knowledge sharing, and collective practices.

Feminist researcher Silvia Federici, in her celebrated book Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, reflects on the link between the privatisation of land and the worsening of women’s condition: “For in pre-capitalist Europe, women’s subordination to men had been tempered by the fact that they had access to the commons and other communal assets (…). But in the new organisation of work every woman (…) became a communal good, for once women’s activities were defined as non-work, women’s labour began to appear as a natural resource, available to all, no less than the air we breathe or the water we drink (…). According to this new social-sexual contract, proletarian women became for male workers the substitute for the land lost to the enclosures, their most basic means of reproduction, and a communal good anyone could appropriate and use at will.”

The consequences of this exacerbation of power relations between the sexes were manifold: women found themselves increasingly confined to the domestic sphere, economically and socially dependent on male authority, and controlled in the management of their bodies by demographic policies that were essential to a society dependent on the flow of labour power. Control of the female body, through the condemnation of contraception and the traditional knowledge associated with care, became central to the emerging capitalist society. The witch-hunts that struck down thousands of women in Europe and America were part of this repression and control.

In the European colonies, similar processes of expropriation and violence were justified by the rhetoric of domination over “savages”. This pattern, based on the extraction of resources and cheap labour, continues to this day: think of the appropriation of indigenous lands in the global South for the exploitation of natural resources. Capitalism and oppression are two sides of the same coin.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in his Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality, wrote: “The first person who, having enclosed a piece of ground, bethought himself of saying This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the real founder of society. From how many crimes, wars and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows, ‘Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.’”

Rousseau’s thinking in this book is not without its problems, and, among other things, fuelled the dangerous myth of the “good savage”, which would in part justify colonialism. Yet these words represent a warning and a hope, inviting us to question the very foundations of society: structures, institutions, and economic systems are not immutable. Change is always possible, provided we have the courage to imagine it.

Autumn in the Garden

The gardener, hands immersed in the soil and in constant contact with plants, might seem to have an idyllic job in the face of urban hassles. But, according to Karel Čapek, nothing could be further from the truth. In his book The Gardener’s Year (1929), Čapek describes the gardener’s problems and tribulations in the face of frost, drought, and the overweening ambitions of small urban gardens. His wonderfully written tale, imbued with irony, offers a reflection on the complexity of human nature, not without a touch of humour and levity. Below is a short extract from the book.

We say that spring is the time for germination; really the time for germination is autumn. While we only look at nature it is fairly true to say that autumn is the end of the year; but still more true it is that autumn is the beginning of the year. It is a popular opinion that in autumn leaves fall off, and I really cannot deny it; I assert only that in a certain deeper sense autumn is the time when in fact the leaves bud. Leaves wither because winter begins; but they also wither because spring is already beginning, because new buds are being made, as tiny as percussion caps out of which the spring will crack. It is an optical illusion that trees and bushes are naked in autumn; they are, in fact, sprinkled over with everything that will unpack and unroll in spring. It is only an optical illusion that my flowers die in autumn-; for in reality they are born. We say that nature rests, yet she is working like mad. She has only shut up shop and pulled the shutters down; but behind them she is unpacking new goods, and the shelves are becoming so full that they bend under the load. This is the real spring; what is not done now will not be done in April. The future is not in front of us, for it is here already in the shape of a germ; already it is with us; and what is not with us will not be even in the future. We don’t see germs because they are under the earth; we don’t know the future because it is within us. Sometimes we seem to smell of decay, encumbered by the faded remains of the past; but if only we could see how many fat and white shoots are pushing forward in the old tilled soil, which is called the present day; how many seeds germinate in secret; how many old plants draw themselves together and concentrate into a living bud, which one day will burst into flowering life—if we could only see that secret swarming of the future within us, we should say that our melancholy and distrust is silly and absurd, and that the best thing of all is to be a living man—that is, a man who grows.

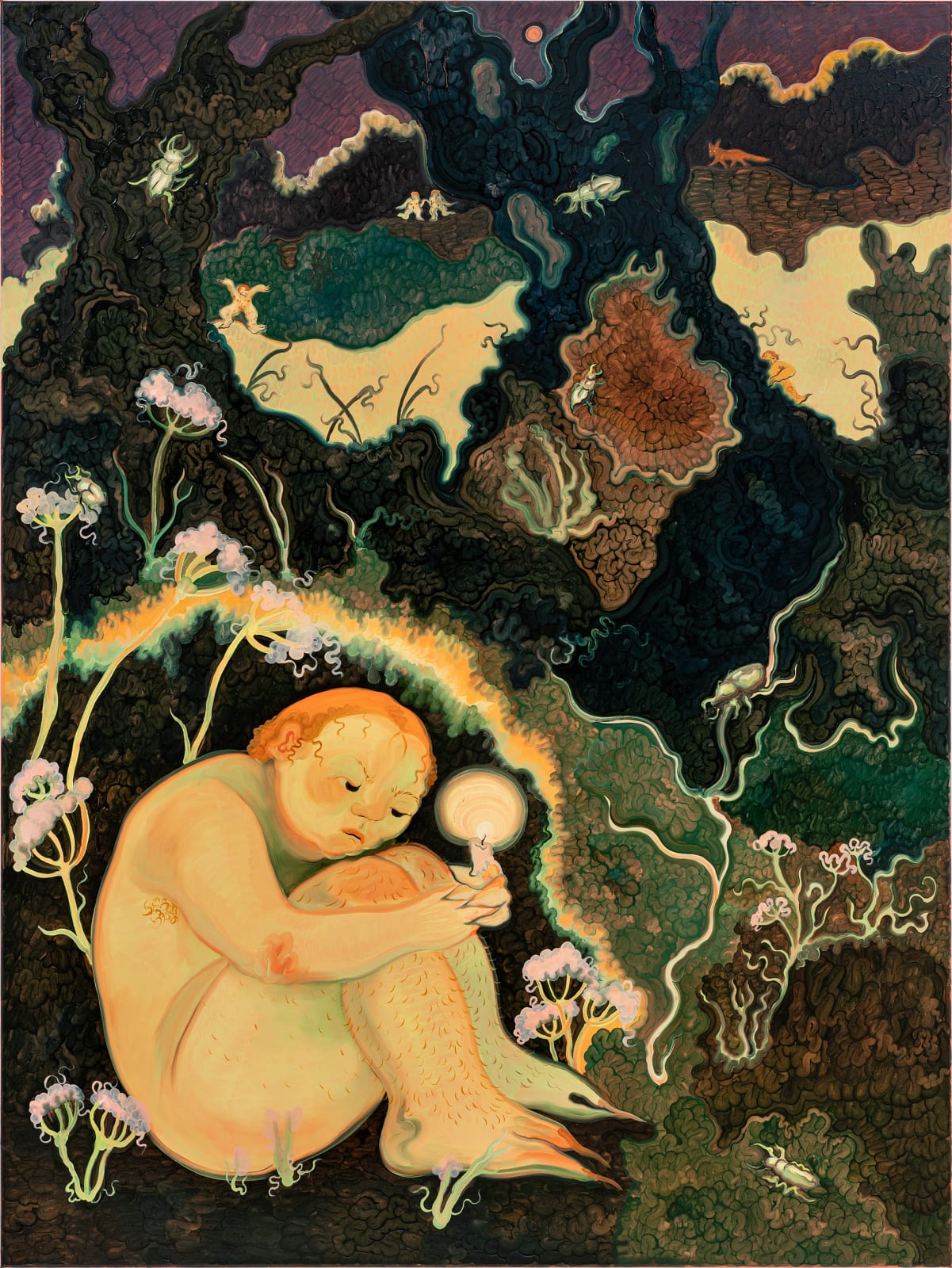

Image: Natália Trejbalová, Few Thoughts on Floating Spores (detail), 2023.

Courtesy of the artist and Šopa Gallery, Košice. Photo: Tibor Czitó.

How happy is the little stone

In this brief poetic composition, Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life, represented by a small stone wandering freely. Far from human worries and ambitions, the stone finds contentment in its elemental existence. Written in the 19th century, the poem reflects the growing disillusionment with industrialisation and urbanisation, which led many to aspire to a more modest and meaningful life.

How happy is the little stone

That rambles in the road alone,

And doesn’t care about careers,

And exigencies never fears;

Whose coat of elemental brown

A passing universe put on;

And independent as the sun,

Associates or glows alone,

Fulfilling absolute decree

In casual simplicity

Image: Altalena.

Ô noble Green

O noble Green, rooted in the sun

and shining in clear serenity,

in the round of a rotating wheel

which cannot contain all the earth’s magnificence,

you Green, you are wrapped in love,

embraced by the power of celestial secrets.

You blush like the light of dawn

you burn like the embers of the sun,

O most noble Viriditas.

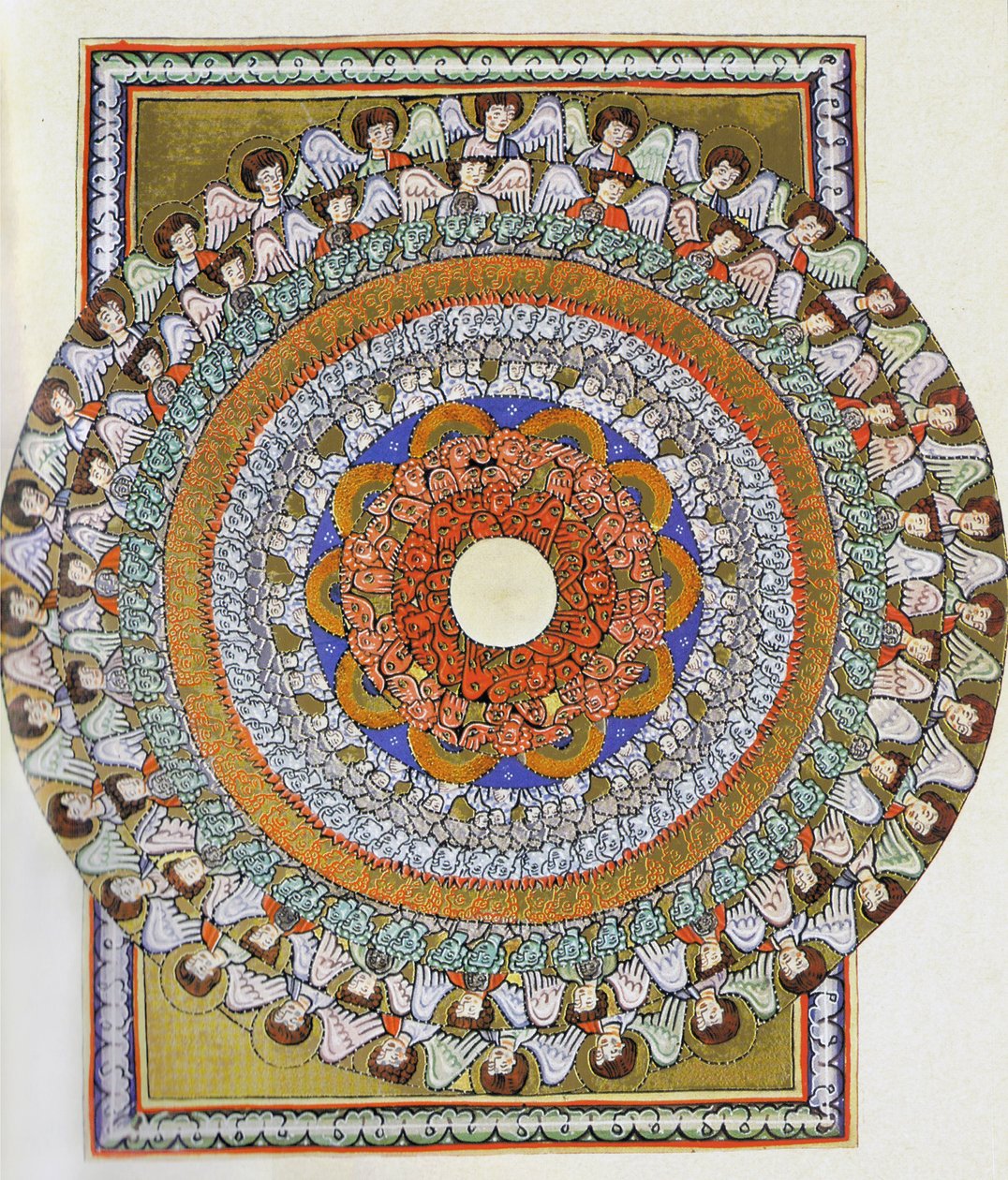

This magnificent hymn to the creative power of “green” is a responsory written and set to music by one of the most brilliant minds of medieval Europe: Hildegard of Bingen, a Christian saint and mystic who lived in the Rhineland in the early 12th century. The tenth daughter of a noble family, from an early age Hildegard was subject to visions and migraines, and for this reason she was destined for the convent already at the age of thirteen. She would only confess and publicly describe her visions at the age of forty-three, prompted by a divine order; a few years later, she founded the monastery of Bingen, of which she was abbess.

Hildegard’s merits are countless: she is the first Western female composer of whom we have written testimony, and her body of music is the most substantial of the era in which she lived to have come down to us. She was an excellent naturalist: her mighty treatise Physica includes 230 chapters on plants, 63 chapters on elements, 63 chapters on trees, and many more on stones, fish, birds, reptiles, and metals, enriched with indications of their medicinal properties: for this reason, some consider her the founder of naturopathy. Her homilies and speeches, imbued with a form of revolutionary vitalism that was unknown to the ecclesiastical thinking of the time, were encouraged and even published with the support of powerful popes and prelates such as Bernard of Clairvaux – a truly exceptional fact in the profoundly misogynistic context of medieval Europe.

Hildegard, however, encountered some difficulty in describing her visions: “In my visions, I was not taught to write like the philosophers. Moreover, the words I see and hear in my visions are not like the words of human language but are like a burning flame or a cloud moving through the clear air.” How do you convey something that cannot be spoken? How do you give voice to new concepts, unknown to the theologians and wise men of the time? How do you criticise the very structure of current thought? Hildegard did not choose the easy way, but decided to invent a new language, which she called Ignota Lingua and which is considered one of the first “artificial languages” ever created (Hildegard is in fact considered the patron saint of Esperanto). Her “dictionary” is actually a glossary of 1011 words, mostly transcribed into Latin and medieval German with the help of a scribe.

Image: Hildegard of Bingen, The hierarchy of angels, sixth vision of the Scivias manuscript.

Among many wonderful linguistic inventions, the concept of viriditas recurs in her writings. Scholar Sarah L. Higley attempts a translation: “viriditas, ‘greenness’ or ‘greening power’, or even ‘vitality’, is associated with all that partakes of God’s living presence, including blossoming nature, the very sap (sudor, ‘sweat’) that fills out leaves and shoots. It is (…) closely associated with humiditas, moisture. Hildegard writes (…) that ‘the grace of God glitters like the sun and sends forth its gifts variously: one way in wisdom (sapientia), another in viridity (uiriditate), a third in moisture (humiditate). In her letter to Tenxwind she compares the virginal beauty of woman to the earth, which exudes (sudat) the greenness or vitality of the grass. The Virgin Mary, of course, is viridissima virga, the ‘greenest branch,’ in Hildegard’s Symphonia. Aridity, on the other hand, represents incredulity, a lack of spirituality, the abandonment of the virtues in their greenness: that which withers and is consumed at the moment of Judgement.

For the inner eye of the mystical naturalist, capable of scrutinising the invisible in the visible, the whole of creation is a flow of divine, gushing green sap. Hildegard attached great importance to the colour green, a symbol of vigour, youth, creative power, efflorescence, fructification, fertilisation, and regeneration. Celebrating greenness for Hildegard is recognising that we are part of a whole, without separation, and serves to maintain the cohesion between soul and body. This radical thinking requires new words, new ways of thinking: inventing a language is an act that helps us understand that everything can be called into question, everything can be imagined from new premises.

Below is a selection of words of the Ignota Lingua from the chapter on trees (translated to English by Sarah L. Higley): an invitation to (re)think everything, starting with the most common words.

Lamischiz — FIR

Pazimbu — MEDLAR

Schalmindibiz — ALMOND

Bauschuz — MAPLE

Hamischa — ALDER

Laizscia — LINDEN

Scoibuz — BOXWOOD

Gramzibuz — CHESTNUT

Scoica — HORNBEAM

Bumbirich — HAZEL

Zaimzabuz — QUINCE

Gruzimbuz — CHERRY

Culmendiabuz — DOGWOOD

Guskaibuz — WINTER OAK

Gigunzibuz — FIG

Bizarmol — ASH

Zamzila — BEECH

Schoimchia — SPRUCE

Scongilbuz — SPINDLE-TREE

Clamizibuz — LAUREL

Gonizla — SHRUB?

Zaschibuz — MASTIC

Schalnihilbuz — JUNIPER

Pomziaz — APPLE

Mizamabuz — MULBERRY

Burschiabuz — TAMARISK

Laschiabuz — MOUNTAIN ASH

Golinzia — PLANE TREE

Sparinichibuz — PEACH

Zirunzibuz — PEAR

Burzimibuz — PLUM

Gimeldia — PINE

Noinz — CHRIST’S THORN

Lamschiz — ELDER

Scinzibuz — SAVIN SAVINE

Kisanzibuz — COTTON TREE

Vischobuz — YEW

Gulizbaz — BIRCH

Scoiaz — WILLOW

Wagiziaz — SALLOW

Scuanibuz — MYRTLE

Schirobuz — MAPLE

Orschibuz — OAK

Muzimibuz — WALNUT

Gisgiaz — CALTROP

Zizanz — BRIAR

Izziroz — THORN TREE

Gluuiz — REED

Ausiz — HEMLOCK

Florisca — BALSAM

The Multiciplity of the Commons

Swiss philosopher Yves Citton’s areas of research range from literature to media theory and political philosophy. We met him as part of our Faire Commun project to discuss a central theme of our research: the commons. Below is a transcript of part of his talk.

I’d like to introduce the “commons” by trying to qualify a certain image – which isn’t wrong, but quite partial – of the commons as pre-existing human appropriation. According to folklore, the Earth and its goods were shared by all animals and all featherless bipeds like ourselves. Then, according to Rousseau’s second discourse, human appropriation became the source of all evils.

This means that the commons are given as they are by nature. It’s true that the air we breathe, for example, wasn’t created by humans so that they wouldn’t die of asphyxiation: on Earth there is air, and we humans benefit from it. It’s a certain layer of the commons that we enjoy naturally, even if we don’t know exactly what nature means.

We can also say that air and water are quite similar commons. On Earth, there’s salt and fresh water, which is drinkable. But if you think about the reality of water today, the water we drink is more or less natural water. We know that it can contain chlorine, that it flows through pipes. Hence, to my mind, water isn’t at all a natural commons. It’s the result of an infrastructure, which can be public, private, or associative; it can be democratic or subject to capitalism. It’s mediated by the community or public institutions. In order to distinguish between public and private commons, I’d call this case public – a government has intervened, made regulations, and financed the pipes.

It’s still a commons, but one that has been constructed by humans, legislation, and political processes. Most of the time, when we talk about the commons today, these elements are inevitably involved. Even forests no longer look like they did before humans brought domesticated species and technologies into them. So I think it’s more realistic to say that the commons include a human artificialisation and preservation dimension. We don’t necessarily need to take care of the air – it’s enough not to pollute it – but we do need to preserve water, pipes, and infrastructures.

It’s interesting to consider another, slightly different model of the commons, i.e. language. Language didn’t precede humans, there was no French language 300,000 years ago; it isn’t an institution, nor an infrastructure regulated by a state that cares for and maintains it. French resides both within and between us. To my mind, it’s the most bizarre and extraordinary model of the commons, existing only because we own it: if all the people who speak French disappeared, there’d be no more French. (That’s without taking into account books written in French, which would remain of course). Knowing where a commons lies, whether it’s artificial or public, is no easy task. For me, what language highlights about the commons is the fact that it can exist without official regulation. The Académie française did not create the French language. Language is reproduced through culture and through children talking to their parents. It’s a commons: it’s neither totally public nor totally private.

Image: Mattia Pajè, Il mondo ha superato se stesso (again), 2020

The French language, air and water are elements that are necessary to our survival, and we’re grateful that they’re available to us: we can define them as positive commons. Conversely, there are negative commons, which are a continuation and a reversal of the latter. Researchers Alexandre Monnin, Diego Landivar, and Emmanuel Bonnet use the term “negative commons” to refer to nuclear waste, to cite only the most telling example. Whether a nuclear power station has public or private status doesn’t change the fact that the resulting waste becomes a collective problem for hundreds of thousands of years to come. It’s clear that nuclear waste is a commons, just as plastic and the climate are. Indeed, the climate, like water, is becoming an element that needs to be maintained if it’s to remain liveable. Some negative commons are therefore blending in with commons that were traditionally seen as positive. These negative commons pose a major problem: they feed our lives (the nuclear power station feeds my computer, which allows me to communicate) but they harm our living environments. Feeding and harming are seen as two sides of the same coin, at the same time. Nuclear energy provides me with electricity but harms future generations through the production of radioactivity.

If we develop this idea further, we can see finance as a good example of a negative commons: finance feeds our investments and the state budget but pollutes our environments by pushing to maximise profits at the expense of environmental considerations. How do we get out of this? How can we dismantle finance? It’s even more interesting to ask whether universities are not a negative commons: knowledge is developed, and research carried out, but the way universities operate can be toxic, with some teachers taking advantage of their power over their students, for example. There’s also bureaucracy that prevents us from doing good work at the same time as framing and structuring that work. There are toxic elements that need to be dismantled, but it’s not easy because they feed us. The intellectual exercise of projecting a negative commons hypothesis onto different subjects is therefore quite revealing.

There’s also the concept of undercommons, a term defined by Afro-American poet and philosopher Fred Moten and activist and researcher Stefano Harney. This term is based on the political ideas of the Black Radical Tradition in the United States. The over-representation of black people, particularly black men, in prisons in the United States today is dramatic, and there’s a continuity between slavery a few centuries ago and racial domination in this country today. The people who emerged from the slave holds were never considered as individuals in their own right. They therefore had to develop other modes of sociality, alternatives to the individualistic socialisation of the homo economicus, the small businessman, the white bourgeois. The communities that were threatened with lynching until a few decades ago and are now victims of police violence, live in conditions of marginalisation or at least do not enjoy the privileges that you and I, as white people in Switzerland or France, have been able to enjoy. These people have therefore developed an alternative, underground form of socialisation: a somewhat paralegal or semi-legal form of solidarity, since US law is made by white people for white people. Instead of seeing this form of solidarity as illegal, it might be seen as a different form of solidarity, outside the law, but one that is worthy of consideration and study. It enables ways of living that feed the commons, even if they’re less visible. And it could prove crucial for all of us: the infrastructures that sustain our luxuries and our forms of economic and social individualisation, as we know them today, may not last indefinitely. It would therefore be in our interests to familiarise ourselves with this form of “survival solidarity”. And of course, before doing so, it’s important to denounce and fight against the persistent oppression that weighs on marginalised populations.

I had the opportunity to work with Dominique Quessada, who came up with the idea of writing the term “commun” (commons in French) as “comme-un” (literally “as one”): his idea being that the commons belongs to everyone and to no one at the same time. The very fact of talking about the commons perhaps presupposes that the term is established, that there are people who see it as a real possibility, and that behind the dissolution of identity and property, the commons is something in which everyone can participate: it’s a plural, it’s neither mine nor yours. Above all, to write it “comme-un” suggests that the unity (of a certain people, of a community) that is often thought of as inherent to the commons is perhaps no more than “acting-as-if we were one”. Faced with the commons, we act “as one”, but we remain diverse, different, and sometimes antagonistic to one another.

Behind the commons there are always two concepts. First of all, there is the principle of unity: who are those who speak of a “commons”? On what do they base themselves? In reality, they can only defend a commons because they’re already united. Secondly, the commons is always a collective fiction: calling something a “commons” means that it is considered as such and thus develops characteristics of a commons. A public park is a public park because it is declared to be one. Thanks to this label, it’s possible to do things in this park that would otherwise have been impossible. But this remains a temporary fiction: a change of regime, a sale, an occupation of the site can always happen. In short, writing “comme-un”, or “as-one”, with a hyphen means asking two questions. Firstly, what is this unity, however heterogeneous, that allows us to say that there is a commons? Secondly, what is the fictional element, the dynamic that allows us to forge a concept that doesn’t exist? The imaginary dimension of the commons always remains central to its defence.

Experiencing the Landscape

In everyday language, the term “landscape” encompasses a variety of notions: it can refer to an ecosystem, a beautiful view, or even an economic resource. However, the complexity of the term can be better understood and approached through the concept of “experience”.

Experience is something that brings us into contact with the outside, with otherness: in this context, the landscape is no longer seen as an object, but rather as a relationship between human society and the environment. An experience is also something that touches us emotionally, that moves and transforms us. Viewing a “landscape” as such helps us realise how much it gives meaning to our individual and collective lives, to the extent that its transformation or disappearance leads to the destruction of sensitive markers of existence in the lives of its inhabitants. Experience can also be seen as a form of practical knowledge or wisdom. It is the kind of knowledge that is acquired by living in a place, which makes the people who inhabit a landscape its experts. Finally, experience is also a form of experimentation: this is the active aspect of our relationship with the world, enabling us to discover and create new knowledge and to bring to life what is yet only potential.

We might take these reflections a step further and argue that human beings live off the landscape—a statement that may seem hyperbolic, but that makes sense if we pay close attention. Indeed, the landscape is the source of our food: we live in the landscape and the latter activates representations and emotions within us. Our relationship with the landscape is dynamic: by changing it, we also change ourselves. It is therefore impossible to avoid entering into a relationship with the landscape. The very choice of ignoring and not ‘experiencing’ a landscape can have practical and symbolic consequences.

It is on the basis of these observations that Jean-Marc Besse wrote La Nécessité du Paysage (the Necessity of the Landscape): an essay on ecology, architecture, and anthropology, as well as an invitation to question our modes of action. In it, the French philosopher warns us against any action on the landscape: an attitude that places us ‘outside’ the said landscape, which, as mentioned above, is simply not plausible. Acting on a landscape means fabricating it, in other words starting from a preconceived idea that ignores the fact that the landscape is a living system and not an inert object. “Acting on therefore involves a twofold dualism, separating subject and object on the one hand, and form and matter on the other.”

So how might we escape this productive yet falsifying paradigm? Besse suggests a change of perspective: moving from acting on to acting with, recognising “that matter is animated to a certain extent” and envisaging it “as a space of potential propositions and possible trajectories”. The aim, in this case, is to interact “adaptively and dynamically”, to practise transformation rather than production. Acting with means engaging in ongoing negotiation, remaining open to the indeterminacy of the process, and being in dialogue with the landscape: in a word, collaborating with it.

Georg Wilson, All Night Awake, 2023

Acting with the soil

The “abiotic” dimension of soil is addressed, among other disciplines, by topography, paedology, geology, and hydrography. However, from a philosophical point of view, soil is simply the material support on which we live. This is where we construct the buildings we live in and the roads we travel on, and it is the soil that makes agriculture possible, one of the oldest and most complex fundamental manifestations of human activity. This “banal” soil is therefore in reality the focus of a whole series of essential political, social, and economic issues, and as such it raises fundamental questions. What kind of soil, water, or air do we want? The environmental disasters linked to the climate crisis and soil erosion or the consequences of the loss of fertility of agricultural and forest land call for collective responses that draw on both scientific knowledge and technical skills, as well as many political and ethical aspects.

Acting with the living

The landscapes we inhabit, travel through, and transform (including the soil and subsoil) are in turn inhabited, travelled through, and transformed by other living beings, animals and plants. In his essay Sur la Piste Animale (On the Animal Trail), philosopher Baptiste Morizot invites us to live together “in the great ‘shared geopolitics’ of the landscape”, by trying to take the point of view of “wild animals, trees that communicate, living soil that works, plants that are allies in the permacultural kitchen garden, to see through our eyes and become sensitive to their habits and customs, to their immutable perspectives on the cosmos, to invent thousands of relationships with them”. To interpret a landscape correctly, it is necessary to take into account the “active power of living beings” with their spatiality and temporality, and to integrate our relationship with them.

Acting with other human beings

A landscape is a “collective situation” that also concerns inter-human relations in their various forms. A landscape is linked to desires, representations, norms, practices, stories, and expectations, and it draws on emotions and positions as diverse as people’s desires, experiences, and interests. Acting with other human beings means acting with a complex whole that includes individuals, communities, and institutions, and drawing on the practical and symbolic—in a continuous process of negotiation and mediation.

Acting with space

Considered through the tools of geometry, space is an objective entity: its dimensions, proportions, and boundaries can be satisfactorily described. However, the space of the landscape cannot be reduced to measurable criteria. In reality, it is an intrinsically heterogeneous space: “locations, directions, distances, morphologies, ways of practising them and of investing in them economically and emotionally are not equivalent either spatially or qualitatively”. Interpreting the space of the landscape correctly therefore means remembering that “numerical” and “geometric” measurements are necessarily false, and that the set of geographies (economic, social, cultural, or personal) that make it up are neither neutral, nor uniform, nor fixed in time.

Acting with time

When we think of the relationship between landscape and time, the first image that springs to mind is that of the earth’s crust and the geological layers that make it up, or that of archaeological ruins buried beneath the surface. In short, we imagine a sort of tidy “palimpsest” of a past time, with which all relations are closed. The time of the landscape, however, should be interpreted according to more complex logics: we need only think of the persistence of practices and experiences in its context, and the fact that landscape destruction is never total: rather, it is transformation. What’s more, the time of the landscape also includes non-human time scales, such as geology, climatology, and vegetation. They are temporalities to which we are nonetheless closely linked. Thus, in reality, the landscape remains in constant tension between past and present.

“Our era,” Jean-Marc Besse concludes, “is one of a crisis of attention. […] Landscape seems to be one of the ‘places’ where the prospect of a ‘correspondence’ with the world can be rediscovered […]. In other words, the landscape […] can be seen as a device for paying attention to reality, and thus as a fundamental condition for activating or reactivating a sensitive and meaningful relationship with the surrounding world”, in other words, the necessity of the landscape.

Listenting to the Sourdough

An interview on cooperative practices and how to include the more-than-human with Marie Preston, artist and lecturer at the University of Paris 8 Vincennes-Saint-Denis (TEAMeD/AIAC Laboratory). Her artistic work takes the form of research aimed at creating works and documents of experience with people who are not necessarily artists. In recent years, her research has focused on the practice of baking, open schools, and libertarian and institutional pedagogies, as well as on women working in the care and childcare sector.

How do co-creative practices compare with political or social participation?

According to philosopher Joëlle Zask, participation in politics should be a combination of taking part, contributing and receiving. Cooperative artistic practices open up spaces where experiences and opinions can be shared, something which is also common to politics. However, political participation aims for an explicit goal, unlike many cooperative artistic practices which are “indeterminate” at first and whose objectives can change through various encounters. This is very much the plastic dimension of the relational forms that are invented in these practices.

Then there is the fact that these shared experiences are expressed in an artistic, tangible form, which is obviously a key difference compared to exclusively political or social participation. However, there is also another distinctive feature: groups are heterogeneous, and the practice only really works when the singularity of each voice in the collective emerges and reflects the group’s complexity. This is a real asset compared with other forms of participation.

Why did you choose the term “cooperative practices”?

Co-creation is a form of participation in which participants, who form a collective, run an artistic project in a cooperative manner and define from the outset what they are going to do together. The artist does not play a specific role in defining the action, whereas in cooperative practices, the artist is at the origin of the project even before the participants’ subjectivities are involved. In reality, however, it is never that simple: the two modes of participation are closely intertwined.

Given that these are processes that unfold over a long period of time, with different levels of involvement, there are phases where the artist is in charge of the project and others where the group acts autonomously, and vice-versa. There is a form of mobility between the different levels of participation.

Hence, I talk about cooperation, which allows the various voices and subjectivities to come to the fore at different times, rather than co-creation, which leaves less room for positions and functions to change and evolve.

How does the recent awareness of more-than-human communities and subjectivities influence cooperative practices?

Let us take the example of “Levain”, a collaborative research project in which I am involved as an artist and which brings together scientists, peasant bakers, craftspeople who do not produce their own wheat, and bakery trainers.

Our group met to identify the impact of the environment and the history of bakery on sourdough biodiversity. We already knew that the sourdough produced by peasants and bakers was biologically rich, and that this richness was fuelled in particular by the tools and hands of the bakers who handled it. This is a truly sympoietic relationship, to use Donna Haraway’s term. The research consists of finding out how far the sourdough feeds to acquire this important microbial diversity.

Fournil La Tit Ferme, 2022 © Marie Preston

In the course of this research, did the question arise of how to gather the voice of the sourdough?

Absolutely. However, before that, there was a whole process of reflection on how to build a common language between scientists, peasants, bakers, and artists, each of whom have their own specific vocabulary. After that, we tried to define how we related to this living entity. We were all aware that it requires special care. However, we soon realised that sourdough also takes care of us, i.e. that without sourdough, the bread we eat would not have the quality it has. Reciprocity – mutual care, as it were – is therefore very important.

Then we realised that we could not make the leaven talk – it cannot actually speak. Instead, we tried to project ourselves: if sourdough were an animal or a plant, what would it be? In answering this question, each of us tells the story of how we see our own sourdough. The examples given reveal very different relationships: domestication for some, cohabitation or friendship for others. Projecting oneself also leads to forms of anthropomorphisation, which in a way reduces the distance between the person and the sourdough, even if this may appear problematic in certain respects.

Finally, there is the question of how one listens and observes. In the animal world, we talk about ethology as the field of zoology that investigates the behaviour of non-human animals, but we can also speak of plant ethology, which in this case involves paying particular attention to how sourdough reacts. This type of listening focuses on the practice of living things, in this case the practice of baking. The scientific work consists of setting up experimental protocols to understand what some bakers know intuitively. In other words, our aim is not to get the leaven to talk, but to actively include it in our research.

Is the growing interest in participative or co-creative practices linked to the need for new imaginaries? In a changing world, what is the role of co-creative practices?

Cooperative artistic practices enable us to tackle societal and political issues in a different way, to open up our imaginations and to do so collectively. This collective act also helps to combat the feelings of anxiety that are generated when one is alone at home worrying about the climate crisis or the extinction of a species, and to become an actor rather than just an onlooker.

What about the interest shown by institutions?

Institutional interest in these practices is quite present in the criticism of cooperative practices, in that they might be said to contribute to legitimise the disengagement of the State from public services.

The associations or art centres that support these practices can offer a response to this question of instrumentalisation that might help minimise or even prevent it by suggesting that the group itself should be in a position to “invent institutionally”.

In other words, we can work on it by coming up with “counter-institutions”. I believe that cooperative artistic practices – because they are constantly reflecting on their own relational modalities – can also act on the structure that allows them to exist, if they have the will to do so.

Image: Bermuda, 2022 © Marie Preston

Public support for participatory practices, judged in ethical rather than aesthetic terms, is often justified in terms of social impact. What are the underlying risks of this approach?

In 2019, we coordinated a book, Cocreation, together with Céline Poulin and Stéphane Airaud, in which we dedicate an entire chapter to the question of evaluating these practices. Just because a project is funded with the aim of having a social impact or to be exclusively artistic does not mean that it should only be assessed through this filter. Of course, artists are going to want to create art, researchers are going to want to find scientific answers, people in civil society are going to want to have fun, make art, or find scientific answers: it is essential to find ways of evaluating these practices with regard to the implications of the people who make up the group, i.e. ultimately, the evaluation takes place downstream and not upstream. Once again, this raises the question not only of the indeterminacy of the project itself, but also the limits of its instrumentalisation.

Given your experience, what do you think are the important questions to ask yourself at the start of a cooperative practice?

Pedagogue Fernand Oury used to say that the first question to ask yourself when you join a group is: “What am I doing here?” Cooperation puts your own vulnerability to the test: are you ready to question your habits, your ways of doing things, to be challenged by the collective and by all the affects that the collective will bring? Are you prepared to let yourself be carried along by what is going to happen? To accept improvisation? To let go of the control you sometimes feel the need to retain when a subject is close to your heart or when you are emotionally involved in the artistic project?

How can one set up a co-creative practice in a community or territory other than one’s own?

I am very interested in reflexive anthropology, i.e. a form of anthropology that questions its own methods of investigation and its relationship with the people it meets, and above all, that incorporates the subjectivity of the researcher. The most important thing, when working in a new place, with people whose practices you do not know, is to listen, observe, be with the people, and be respectful of their differences, ethically and scrupulously.

Finally, you have to get involved and accept contradiction, which goes back to what we said earlier about the questions you need to ask yourself. I also think it is important not to arrive empty-handed: you have to be generous in your involvement and in every way you can.

Wild Bread

Il pane selvaggio (Wild Bread, 1980) is an essay by Italian philologist, historian and anthropologist Piero Camporesi about the experience of hunger in Europe in the modern age. Hunger in the Global North may appear to be a distant issue, but access to adequate, healthy and affordable food is still affected by profound inequalities both across the world and within single communities.

The “wild bread” to which the title refers describes the bread of the poor, who, to cope with grain shortages in times of famine, began to grind flour from roots, seeds, mushrooms—anything that could fill their stomachs and could be gathered freely on the limited non-private land available. The end product was stale, toxic and non-nutritious bread, which often also caused hallucinatory states.

The educated, rich and powerful men who reported the history of famines had the option of neglecting the experience of the most fragile people. Camporesi has therefore traced the accounts of those who could never aspire to a piece of white bread on their table in folk literature, as in the 16th-century song Lamento de un poveretto huomo sopra la carestia (Lament of a Poor Man Over Famine).

A bad thing is famine

that causes man to be always in need,

fasting against his will,

Lord God, send it away…

I sold the bedsheets,

I pawned the shirts

such that now my uniform

is that of a rag-pedlar,

to my suffering and greater distress

only a piece of sackcloth

covers this flesh of mine.

And even more it pains my heart

to see my child

say to me often, from hour to hour,

‘daddy, a little bit of bread’:

it seems that my soul leaps out

at not being able to help

the little one, oh terrible fate!

A bad thing is famine.

If I leave my house

and I ask a penny for God

all say ‘get some work’,

‘get some work’; oh proud destiny!

I don’t find any, despite all efforts

so I stay with head bent low,

oh fortune, cruel and evil

A bad thing is famine.

I have no more covers in the house

the pots I have sold

and I have sold the pans;

I am clean through and through…

Often my bread is made from

the stems of plants,

In the earth I make holes

for diverse and strange roots

and with that we grease our snouts:

and if there were enough for every tomorrow

it wouldn’t be so bad

A bad thing is famine.

Image: Luca Trevisani, Ai piedi del pane, 2022.

Oplà. Performing Activities, curated by Xing, Arte Fiera, Bologna.

Bodies of Water

The transition of life from water to land is one of the most significant evolutionary milestones in the history of life on Earth. This transition occurred over millions of years as early aquatic organisms adapted to the challenges and opportunities presented by the terrestrial environment. One of those was the need to conserve water: living beings, in a way, had “to take the sea within them”, and yet, although our bodies are composed mostly of it, biological water actually counts for just 0.0001% of Earth’s total water.

Water is involved in many of the body’s essential functions, including digestion, circulation and temperature regulation. Nevertheless, our bodily fluids, from sweat to pee, saliva and tears, are not just contained within our individual bodies but are part of a more extensive system that includes all life on Earth, blurring the boundaries between our bodies and more-than-human organisms, connecting us to the world around us. Scholars described this idea as hypersea: the fluids that flow through our bodies are connected to the oceans, rivers and other bodies of water that make up the planet and are part of a larger system that connects all living beings together.

Recognising the interconnectedness of all life on Earth and the role that water plays in this interconnected web can help us better understand our place in the world and the importance of working together to protect and preserve this precious element. However, to fully grasp the consequences of this perspective, it is necessary to consider some significant issues addressed by scholar Astrida Neimanis, the theorist of hydrofeminism, in her book Bodies of Water.

One of the main contributions of hydrofeminism to the discussion on bodies of water is the proposal to reject the abstract idea of water to which we are accustomed. Water is usually described as an odourless, tasteless and colourless liquid and is told through a schematic and de-territorialised cycle that does not effectively represent the ever-changing, yet situated, reality of water bodies. Water is mainly interpreted as a neutral resource to be managed and consumed, even though it is a complex and powerful element that affects our identities, communities and relationships. Deep inequalities exist in our current water systems, shaped by social, economic and political structures.

Neimanis shares an example explicitly related to bodily fluids. The Mothers’ Milk project, led by Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook, found that women living on the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation had a 200% greater concentration of PCBs in their breast milk due to the dumping of General Motors’ sludge in nearby pits. Pollutants such as POPs hitch a ride on atmospheric currents and settle in the Arctic, where they concentrate in the food chain and are consumed by Arctic communities. As a result, the breast milk of Inuit women contains two to ten times the amount of organochlorine concentrations compared to samples from women in southern regions. This “body burden” has health risks and affects these lactating bodies’ psychological and spiritual well-being. The dumping of PCBs was a human decision, but the permeability of the ground, the river’s path and the fish’s appetite are caught in these currents, making it a multispecies issue.

Hence, even though we are all in the same storm, we are not all in the same boat. The experience of water is shaped by cultural and social factors, such as gender, race and class, which can affect access to safe water and the ability to participate in water management. The story of Inuit women makes it clear how water, even if it is part of a single planetary cycle, is always embodied, and so are bodies of water with their complex interdependence. While hydrofeminism invites us to reject an individualistic and static perspective, it also reminds us that differences should be recognised and respected. Indeed, it is only in this way that thought can be transformed into action towards more equitable and sustainable relationships with all entities.

Neimanis also approaches the role of water as a gestational element, a metaphor for this life-giving substance’s transformative yet mysterious power. Like the amniotic fluid that surrounds and nurtures a growing animal, water can support and sustain life, nourish and protect, and foster growth and development. In this sense, water can be seen as a symbol of hope and possibility, a source of renewal and regeneration that can help us navigate life’s challenges and transitions. Like a gestational element, water has the power to cleanse, heal and transform. While seeking to find our way in a constantly changing world, we can look to water as an inner source of strength and inspiration, a reminder of life’s resistance and adaptability and the potential that lies within us all.

Image: Edward Burtynsky, Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, Baja, Mexico, 2012. Photo © Edward Burtynsky.

Intimity Among Strangers

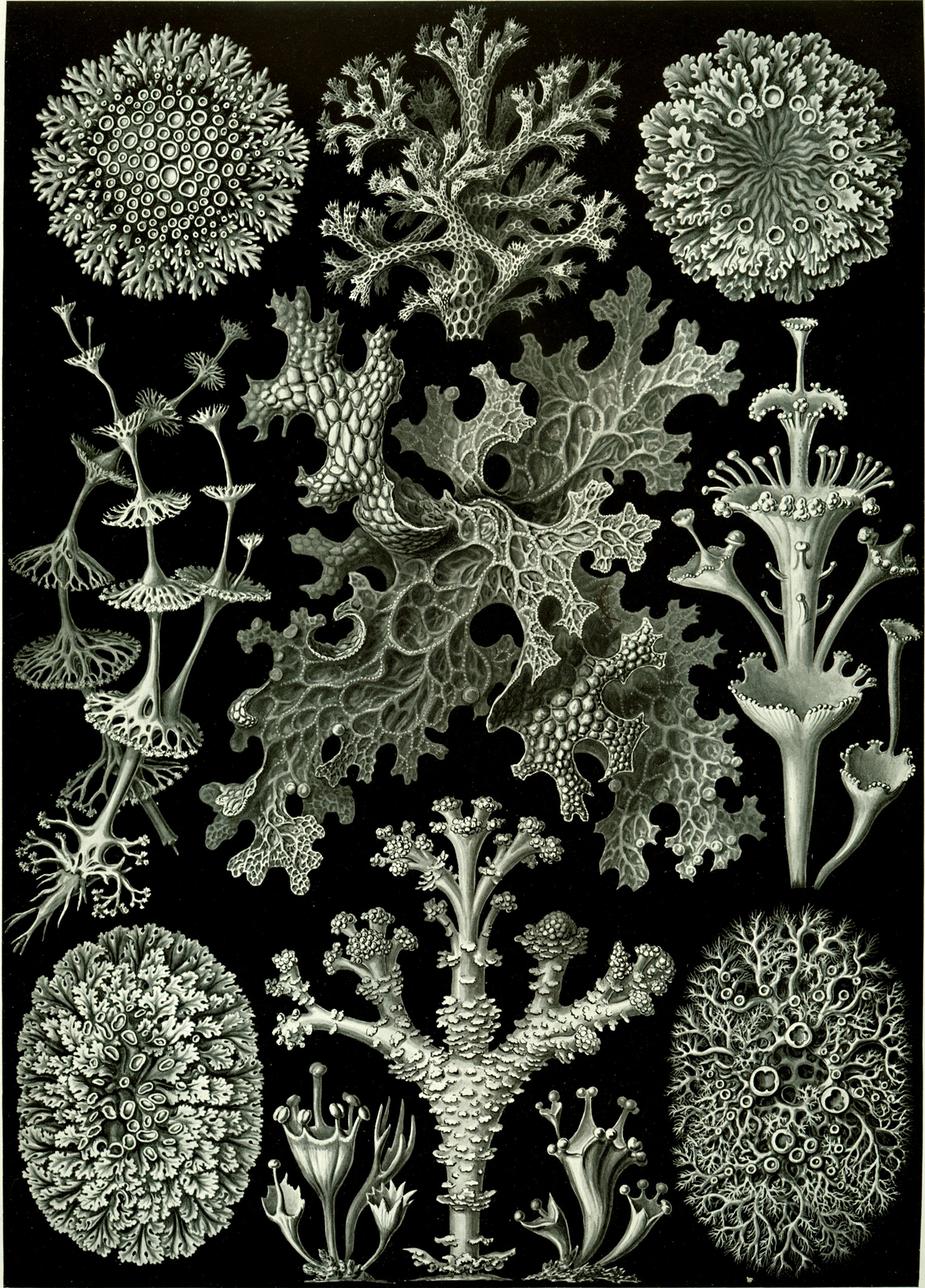

Covering nearly 10% of the Earth’s surface and weighing 130.000.000.000.000 tons—more than the entire ocean biomass—they revolutionised how we understand life and evolution. Few would probably bet on this unique yet discrete species: lichens.

Four hundred and ten million years ago, lichens were already there and seem to have contributed, through their erosive capacity, to the formation of the Earth’s soil. The earliest traces of lichens were found in the Rhynie fossil deposit in Scotland, dating back to the Lower Devonian period—that of the earliest stage of landmass colonisation by living beings. Their resilience has been tested in various experiments: they can survive space travel without harm; withstand a dose of radiation twelve thousand times greater than what would be lethal to a human being; survive immersion in liquid nitrogen at -195°C; and live in extremely hot or cold desert areas. Lichens are so resistant they can even live for millennia: an Arctic specimen of “map lichen” has been dated 8,600 years, the world’s oldest discovered living organism.