laboratoire écologie et art pour une société en transition

Peau Pierre

Peau Pierre is a project by Ritó Natálio and least which aimed to make the issue of transition, both gender and environmental, visible in public discourse. Peau Pierre disseminated an ecotransfeminist-based ecology of education, i.e. the conviction that the ideology that underpins forms of oppression such as those based on race, class, gender, sexuality, physical ability, and species is the same one that enshrines the oppression of nature.

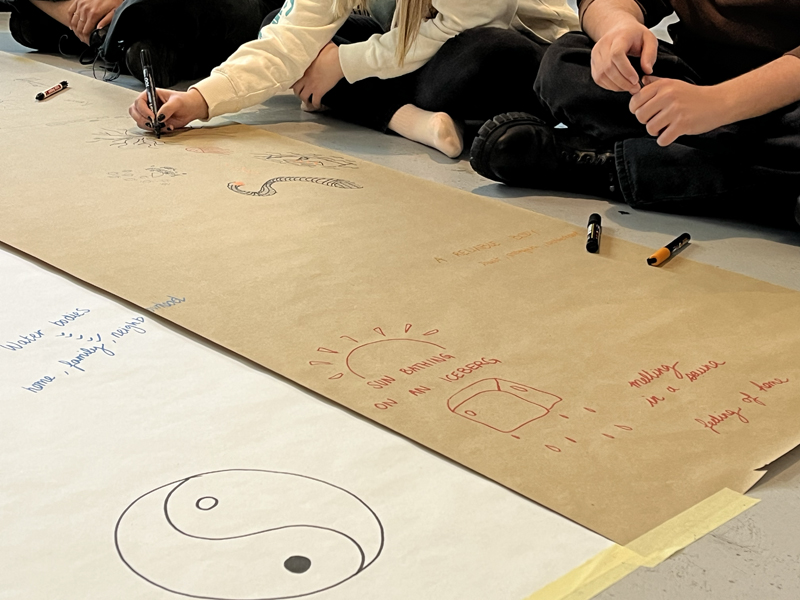

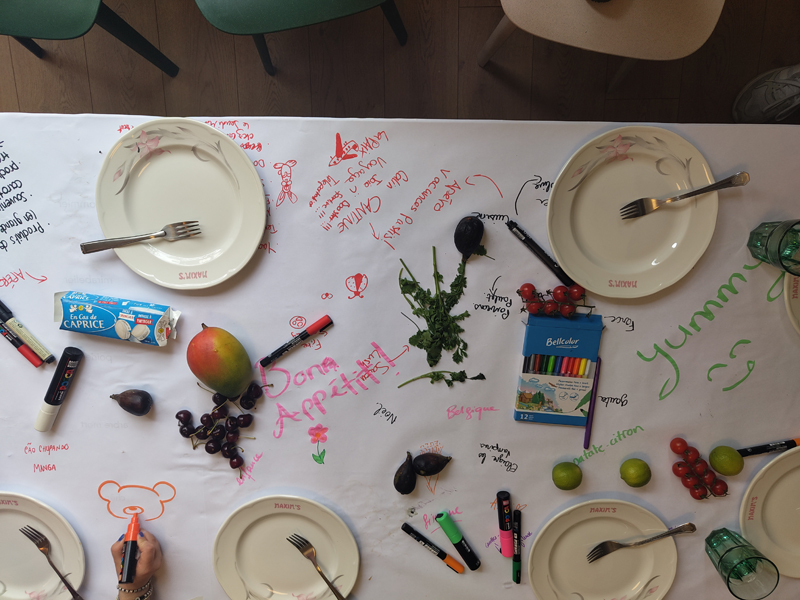

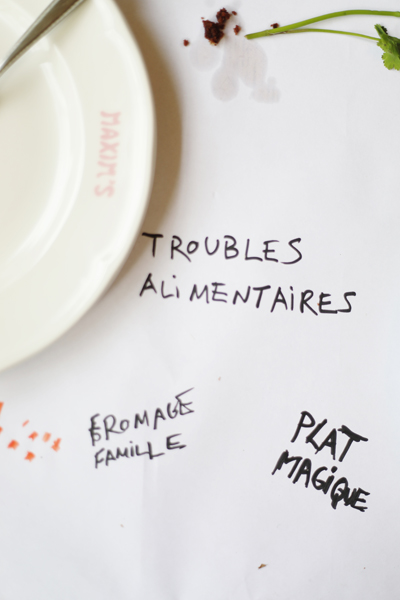

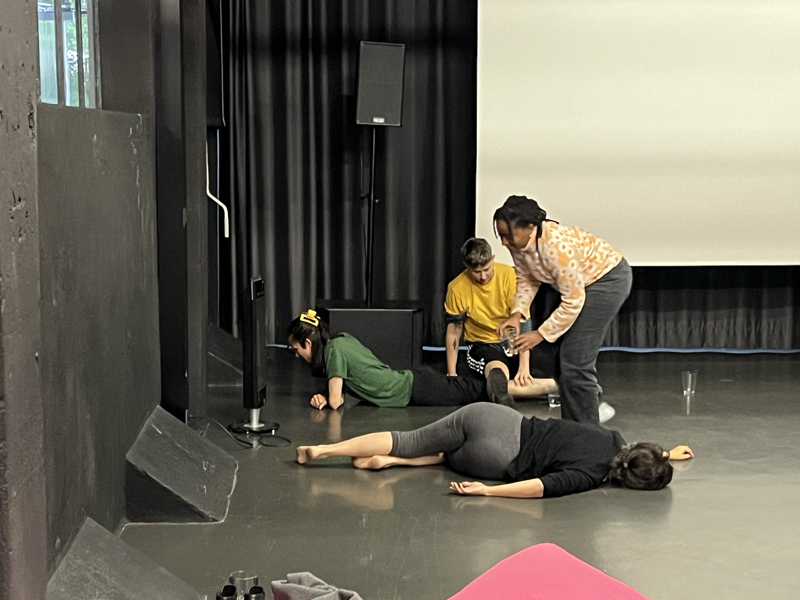

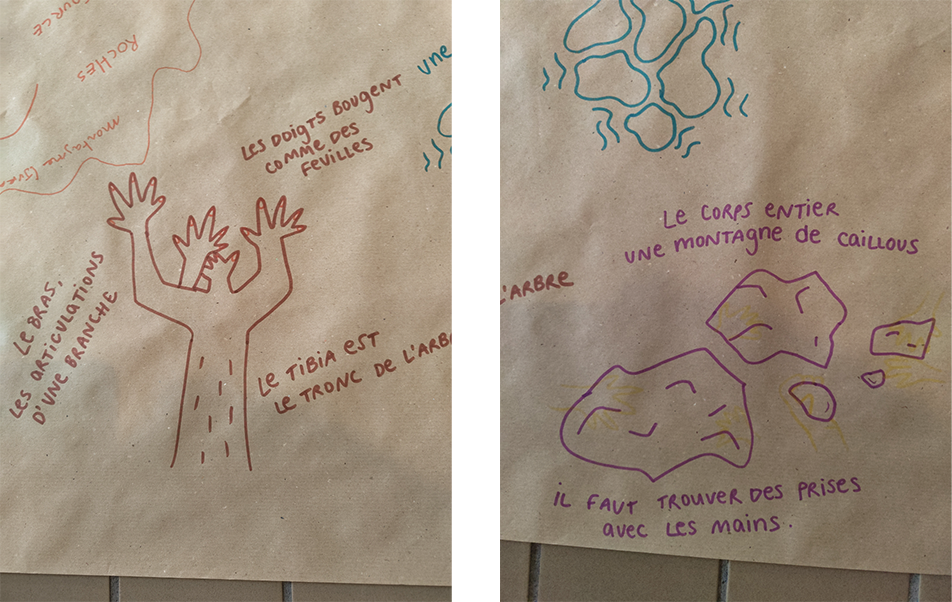

Performative exploration workshops were organised, and a research team gathered to analyse and collect historical documents, archiving ecotransfeminist memories from Switzerland. At the same time, the practice of narrative and fictional writing was addressed in order to consider other perspectives and offer concrete political solutions to ecological concerns.

The project involved researchers and students from a range of university departments (gender studies, humanities, and ecology), local associations working with marginalised groups, and young people from the LGBTQIAP+ community.

The team of Peau Pierre co-created a Glossary of Transition to develop a form of environmental education that encourages artistic practices as a means of understanding and applying ecological theory to societal challenges.

The workshops and research group of Peau Pierre co-created the Glossary of Transition, an evolving and open tool of ecotransfeminist speculative fiction.

You can read it at this link, and listen to an audio capsule at this link.

the research

The first phase of the project focused on meetings and interviews with members of the LGBTQIAP+ community in Geneva and academics from various disciplines (environmental sciences, medicine, ecology, gender studies, visual arts) in French-speaking Switzerland, with the goal of forming a transdisciplinary research group. Through a series of meetings in Geneva and individual research on the local LGBTQIAP+ history (January-June 2024), the research group identified critical issues and connections between gender transition and environmental transition. These included waterborne hormonal pollution, the relationship between alpine exploration and gender identity, the evolution and regression of laws governing gender affirmation, mining practices as a metaphor, and the invisibility of the queer community in public spaces.

the workshops

Ritó Natálio, in collaboration with resident artist Jonas Van, led a series of workshops to explore the possibilities of embodied knowledge. Imagining a landscape by touching a study partner’s back, creating a human chain to transport water using the body, or sharing memories and stories over a meal—each of these experiences serves as a starting point for new, transformative imaginaries of political action. The workshops were organized with young people, students (UNIGE, Master’s in Innovation, Human Development, and Sustainability), artists from L’Abri (a cultural space dedicated to supporting and promoting emerging artists), and the Le Refuge association (a support center for LGBTQ+ youth under 18 facing difficulties).

tools for political imagination

Inspired by the experiences of the research group and the workshops, the first entries of a Glossary of Transition were published. This text, through fiction, conceptually shifts certain terms and notions related to environmental transition (e.g., corps-glacier) or gender transition (e.g., hormones) toward an ecofeminist perspective. The Glossary is distributed as a tool for political imagination. At the same time, resident artist Jonas Van created Corps Voyageur, a audio capsule that artistically documents key moments from the initial workshops.

newsletter

All participatory actions and locations will be communicated on our website and via least’s newsletter.

artistic team

Ritó (Rita Natálio)

Jonas Van – resident artist least

research group

Denise Medico (psychologist and sexologist, founder of Centre3 – Lausanne and PhD candidate at UQAM – Montréal)

Cyrus Khalatbari (artist, designer, and PhD candidate at HEAD – Genève, EPFL – Lausanne)

Stella Succi (art historian and researcher least)

least would like to thank all the people that contributed to the project by sharing their time, knowledge and resources:

Centre3; Fondation Agnodice; Karine Duplan; Ilana Eloit; La Manufacture; L’Abri; Le Refuge; Lucrezia Perrig; Nicolas Senn; Maison Saint-Gervais; Miriam Tola; UNIGE / Marlyne Sahakian; UNIGE / Peter Bille Larsen.

media

Transforming Knowledge

Reading

Every knowledge is rooted in specific contexts and experiences.

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

The “life” of objects

Reading

Matter should not be considered as passive and inert, but as infused with intrinsic vitality.

d'un champ à l'autre / von Feld zu Feld

Peau Pierre

How happy is the little stone

Reading

Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life.

Peau Pierre

Arpentage

Faire commun

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Mineral Life

Reading

Recognising our entanglement with geological processes.

Peau Pierre

Rethinking Transition

Reading

An interview with Denise Medico.

Peau Pierre

The Gesamthof recipe: A Lesbian Garden

Reading

The Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, a garden without the idea of an end result.

CROSS FRUIT

Peau Pierre

Peau Pierre: an audio capsule

Audio

“When our skins finally touch, water is the intermediary in this encounter”.

Peau Pierre

Spillovers

Reading

A sci-fi essay and sex manual created by Rita Natálio.

Peau Pierre

Bodies of Water

Reading

Embracing hydrofeminism.

Vivre le Rhône

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

Faire commun

Intimity Among Strangers

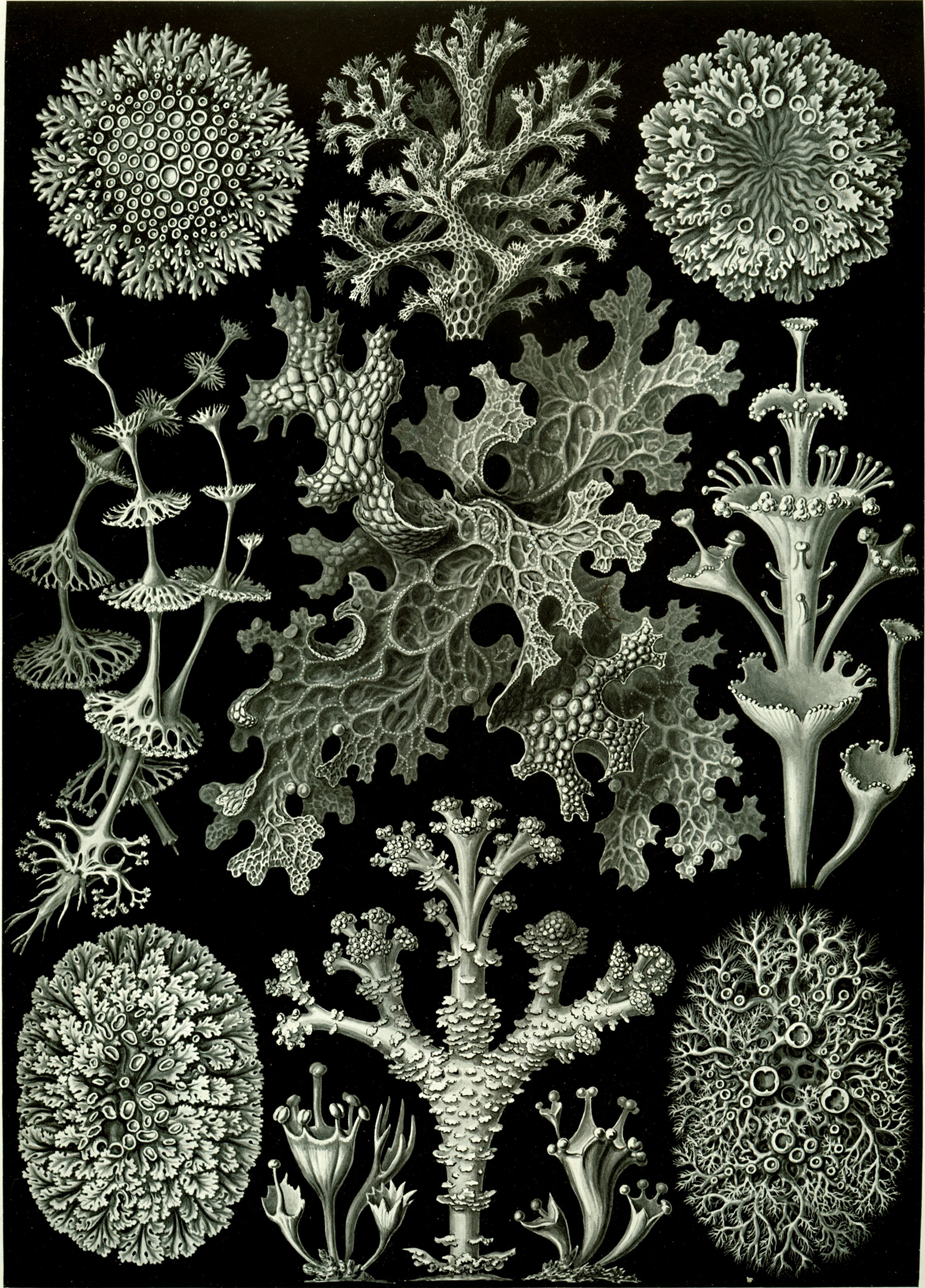

Reading

Lichens tell of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option

Common Dreams

Faire commun

CROSS FRUIT

Learning from mould

Reading

Even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

GLOSSARY OF TRANSITION (T — T) by Ritó Natálio

Reading

A collective, ecotransfeminist speculative fiction.

Peau Pierre

Transforming Knowledge

Knowledge – and scientific knowledge in particular – is often perceived as something neutral, universal and abstract. This illusion, which lends it authority and prestige, conceals the fact that all knowledge is rooted in specific contexts and embodied in experiences. Every act of research is born of an encounter with matter and with others. It is within this tension that many contemporary theories have mounted a radical critique of the dominant view, inviting us instead to think of knowledge as an embodied, relational experience.

In Situated Knowledges, Donna Haraway dismantles the fiction of “objective” science. She reminds us that every gaze is always partial and situated: there is no neutral point of view, only embodied perspectives, i.e. perspectives that carry responsibility and call for a “science project that offers a more adequate, richer, better account of a world, in order to lie in it well and in critical, reflexive relation to our own as well as others’ practices of domination and the unequal parts of privilege and oppression that make up all positions. In traditional philosophical categories, the issue is ethics and politics perhaps more than epistemology.” For Haraway, objectivity does not mean hypocritically erasing partiality but rather making it explicit and owning up to the relationships that make it possible. This shift transforms science into what she calls a “successor science”: no longer the abstract possession of universal truths, but a situated practice that acknowledges its grounding in bodies and histories.

In bell hooks’ pedagogy, this principle takes on a concrete form. In Teaching to Transgress, the classroom is not portrayed as a neutral space for the transmission of knowledge, but as a place shaped by identities, emotions, desires and reciprocal relations. Teaching becomes a “practice of freedom”: not merely the communication of content, but the opening up of a space where lived experience rightfully enters the learning process and where pedagogical formats are continually re-examined and co-created collectively within what hooks calls the learning community. In contrast to the academic ideal of aseptic, disembodied didactics, hooks – writing from her position as a Black woman in a white university – asserts the value of the body, of personal histories and of process itself as necessary conditions of learning. For hooks, the aim of teaching is to guide action and reflection in order to transform the world, to convert the will to know into a will to become.

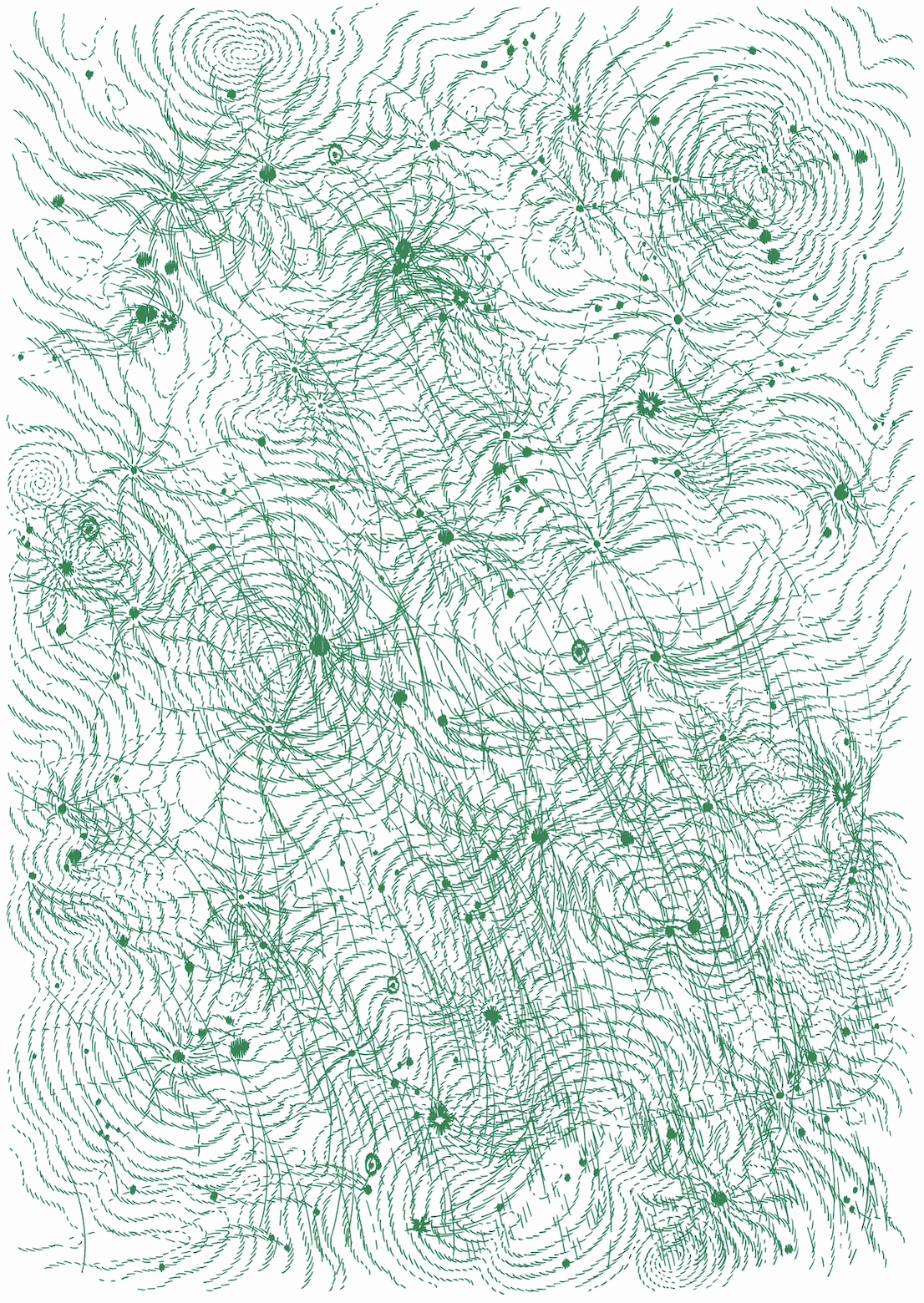

Drawing: Anaëlle Clot.

Another influential position in this regard can be found in Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s writings on Amerindian perspectivism, which he defines as the idea “that the world is inhabited by different kinds of subjects or persons, human and non-human, who apprehend reality from distinct points of view.” At first glance, this might sound like relativism, but in fact it overturns the relativist hypothesis: it is not that there is a single physical “nature” interpreted by a plurality of cultures. For perspectivism, on the contrary, there is a single culture, shared by all beings, including non-human animals, who see themselves as persons and participate in sociality and belief. What exists instead is a multiplicity of “natures”, since each type of being perceives and inhabits a different world. Thus, jaguars see blood as manioc beer: what might appear to us as an objective given is, within this cosmology, the result of an embodied perspective. One consequence of this ontology is a reversal of the Western conception of culture: “creation-production is our archetypal model of action (…) while transformation-exchange would probably fit better the Amerindian and other non-modern worlds. The exchange model of action supposes that the other of the subject is another subject, not an object; and this, of course, is what perspectivism is all about.”

With Making by Tim Ingold, the discourse on embodied knowledge is tightly interwoven with the experience of making. Rather than the accumulation of data, he values the cultivation of a sensitive, bodily attention, “against the illusion that things can be ‘theorised’ independently of what is happening in the world around us.” From this perspective, “the world itself becomes a place of study, a university that includes not just professional teachers and registered students, dragooned into their academic departments, but people everywhere, along with all the other creatures with which (or whom) we share our lives and the lands in which we – and they – live. In this university, whatever our discipline, we learn from those with whom (or which) we study. The geologist, for example, studies with rocks as well as with professors; he learns from them, and they tell him things. Likewise, the botanist studies with plants and the ornithologist with birds.” Hence his critique of traditional academic forms, which claim to explain the world as if knowledge could be constructed after the fact, by excluding the body and practice. For Ingold, by contrast, thinking and making are inseparable: “materials think in us, as we think through them.” It is in this spirit that the introduction of artistic and manual practices into his teaching plays a central role: it demonstrates that knowledge arises from the experimenting body, in correspondence with materials that actively take part in transformation. The ultimate aim is not to document from the outside, but to transform: if learning changes us, it must also be given back to the world, opening up other possibilities of relation.

These diverse voices converge on a single point: knowledge is never detached from the world, but takes shape through its interaction with bodies, materials and relationships. This is not to deny the rigour or the importance of academic institutions, but to stress that knowledge is diminished when it erases the embodied and situated conditions from which it arises. Focusing on these dimensions is to transform knowledge, from an instrument of domination into an ecological practice of coexistence, where disciplinary boundaries blur and description gives way to collective, transformative experience. It is within this space of research and experimentation that least positions its work: approaches that bring together transdisciplinary teams in which everyone has an equal place and commits to crossing the frontiers of their own discipline; approaches that privilege process over outcome; and approaches that, through artistic practice, open new ways of developing and transmitting knowledge.

The “life” of objects

The relationship between human beings and objects, between subject and matter, is traditionally considered in terms of use, or even domination. Western philosophy, with a few exceptions, has generally made a strict distinction between the human world and the world of things, attributing to the former an absolute primacy in terms of agency and intentionality. Nevertheless, in our daily experience, this separation between us and the world of objects is much more nuanced, dynamic and interactive.

From a pragmatic point of view, one need only think of the myriad of technologies that surround us, from forks to computer networks that influence our lives. On a symbolic level, objects also play a fundamental role in the construction of individual and collective identities, actively participating in the formation of cultural, emotional and social representations. From this perspective, the strict distinction between subject and object fades away, giving way to a more complex network of mutual interactions.

In this context, American theorist Jane Bennett came up with the concept of “vibrant matter”. Matter should not be considered as passive and inert, but as infused with intrinsic vitality. Objects and matter are not reduced to simple instruments subject to human will, but exercise an agency of their own, influencing humans and actively participating in the construction of the social and political world.

According to Bennett, reality must be understood as a series of “assemblages”, where living and inert matter, animals and objects, particles, ecosystems and infrastructures all contribute equally to the production of effects. In her book Vibrant Matter, she cites and analyses the major power outage that struck the North American grid in 2003, plunging millions of people into darkness – an event that shows the extent to which an entity that is supposedly devoid of agency can exert a decisive influence on humans. As she writes: “To the vital materialist, the electrical grid is better understood as a volatile mix of coal, sweat, electromagnetic fields, computer programmes, electron streams, profit motives, beat, lifestyles, nuclear fuel, plastic, fantasies of mastery, static, legislation, water, economic theory, wire, and wood – to name just some of the actants.” By analysing the chain of events that led to this blackout, Bennett highlights its emergent character, which calls into question traditional concepts of responsibility and causality, as well as the distinction between subject and object. While such an approach is obviously manifested in a large-scale event, it can be extended to our entire experience of the world.

Moreover, on a scientific level, the traditional distinctions between living and non-living matter, organic and inorganic, are tending to blur. Materials considered to be inert are proving capable of growth, self-organisation, learning and adaptation to the environment. The idea that intelligence is an exclusively human trait is now obsolete and misleading: this is the premise on which Parallel Minds by chemist and theorist Laura Tripaldi is based. In this book, she focuses in particular on the concept of interface, which we often associate with digital technologies, but which, in chemistry, refers to a three-dimensional space with mass and thickness, where two distinct substances come into contact. In this space of interaction, materials adopt unique behaviours: Tripaldi takes the example of water, which, on contact with a smooth surface, takes the form of a drop.

Drawing: ©Anaëlle Clot.

More than a technical notion, the interface invites us to rethink our relationship with matter: “In this sense, the interface is the product of a two-way relationship in which two bodies in reciprocal interaction merge to form a hybrid material that is different from its component parts. Even more significant is the fact that the interface is not an exception: it is not a behaviour of matter observed only under specific, rare conditions. On the contrary, in our experience of the materials around us, we only ever deal with the interface they construct with us. We only ever touch the surface of things, but it is a three-dimensional and dynamic surface, capable of penetrating both the object before us and the inside of our own bodies.”

The act of “touching” is also central to the thinking of philosopher and physicist Karen Barad. In her book On Touching – The Inhuman that Therefore I Am, Barad explains that, from the point of view of classical physics, touch is often described almost as an illusion: indeed, the electrons that make up the atoms of our hands and the objects we touch never actually meet but repel each other due to electromagnetic force. This means that any contact experience always occurs at a minimum distance, thus defying our sensory intuition.

Barad goes even further by analysing the question through quantum field theory, which introduces the possibility that matter is not something static and defined, but rather a continuous tangle of relationships and possibilities. The separation, which seems obvious to us, between one body and another fades away, because the boundaries between the “self” and the “other” are continually redefined, in a process that Barad calls intra/action and which would constitute the very essence of our reality – a reality where everything is constantly co-produced and co-determined. This principle implies that identity is not something pre-established but the result of infinite variations and transformations, according to a queer and non-binary model.

These approaches invite us to rethink our relationship with everyday objects and with matter in general. If matter has an agency of its own, we must recognise our belonging to a complex and interconnected system, with philosophical, political and ecological implications. Accepting that matter shapes us as much as we shape it, implies increased responsibility for our technological and environmental impact and, ultimately, for ourselves, as we inhabit assemblages, interfaces and intra/actions.

How happy is the little stone

In this brief poetic composition, Emily Dickinson celebrates the happiness of a simple, independent life, represented by a small stone wandering freely. Far from human worries and ambitions, the stone finds contentment in its elemental existence. Written in the 19th century, the poem reflects the growing disillusionment with industrialisation and urbanisation, which led many to aspire to a more modest and meaningful life.

How happy is the little stone

That rambles in the road alone,

And doesn’t care about careers,

And exigencies never fears;

Whose coat of elemental brown

A passing universe put on;

And independent as the sun,

Associates or glows alone,

Fulfilling absolute decree

In casual simplicity

Image: Altalena.

Mineral Life

For centuries, the implicit assumption that the mineral realm operates independently from that of life has endured, creating, as in many fields of knowledge, an artificial dichotomy: in this case, between the world of rocks, minerals and crystals – which pertains to geology – and the world of the living – which concerns biology. The understanding of the origin of fossils in the 19th century blurred for the first time the boundaries between the two disciplines, sparking both a scientific and philosophical revolution.

Beyond the gradual replacement of organic matter by minerals resulting in fossils, we now know that the molecules that compose rocks, our bodies and all living things are ultimately the same, and indeed, life is assumed to have arisen because of a geochemical process made possible by the combination of water, air, minerals and energy. Over the past two decades, scholars such as geologist Robert Hazen have highlighted how life and minerals on our planet have in fact co-evolved. Although rocks are perceived as fixed and unchanging entities, especially when compared to the variability of living things, the emergence of life on our planet has actually contributed to profound changes in geology. Indeed, the Earth is characterised by astonishing geo-diversity, estimated to be about ten times greater than that of the other planets in the Solar System, and life has played an essential role in the processes that have led to this differentiation.

A first major breakthrough occurred 2.5 billion years ago with the appearance of a form of photosynthesis in the metabolism of slime algae, releasing oxygen and transforming the atmosphere into an oxidising environment. Oxygen is a corrosive gas that has caused major changes in the minerals of our planet: thousands of specimens, including turquoise and malachite for example, have formed in the surface layers of the Earth’s crust as a result of interactions between oxygen-rich waters and pre-existing minerals. Before the increase in oxygen concentration, such reactions could not have occurred and these changes originated new ecological niches, contributing to the birth and evolution of new life forms.

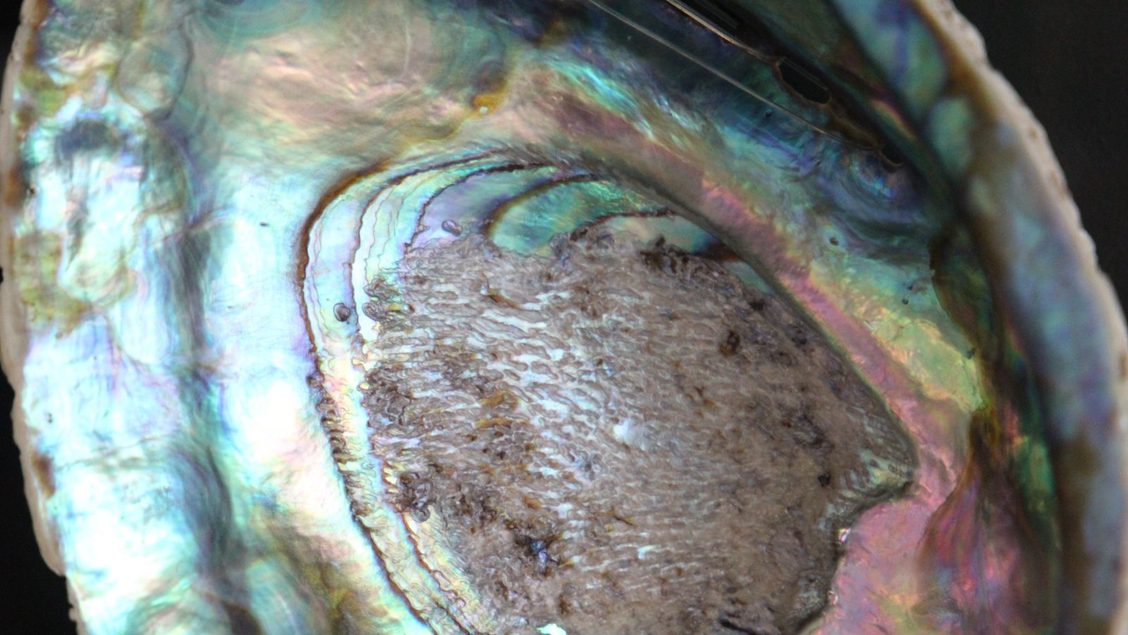

Another crucial step was the process of biomineralisation: around 580 million years ago, in an evolutionary course that is yet to be fully explained, some animals acquired the ability to develop protective hard parts by exploiting minerals such as calcium carbonate and silica: within a few tens of millions of years, carapaces, teeth, claws, spines, shells and corals became widespread and layered in the sedimentary rocks that now cover a large part of the Earth’s surface.

Image: Marina Cavadini, Oyster, 2022, digital print. Courtesy: the artist and The Address Gallery.

Lastly, among the many examples, let us not forget the formation of the so-called fossil fuels, resulting from the natural transformation, over millions of years, of organic matter buried underground into gradually more stable and carbon-rich forms. Oil, methane and coal have in fact indirectly brought to light how biology and geology are interrelated, due to the fundamental role they play in the Anthropocene, the geological era that we are currently living in. The term Anthropocene emphasises the changes that one living species, namely humans, have and continue to provoke in the planet’s cycles, to such an extent that they have left their mark on the geological record with a speed and severity previously unknown.

In the last decades, the interplay between life and geology has taken a new dimension, especially in the context of technology production and the extraction of rare earths. The demand for these critical elements, which are essential in manufacturing the high-tech devices that now permeate our daily lives, has led to extensive mining operations that impact the ecological balance: the act of writing or reading this very newsletter, for instance, is intertwined with extractivism, a practice and approach that is associated with environmental degradation and human rights concerns. Furthermore, from electric vehicles to solar panels, the technologies that have been proclaimed as unquestionably green solutions to the ecological crisis require the exploitation of components that are once again intensively mined: whether green or not, the capitalistic paradigm perpetuates a cycle of exploitation which is rooted in hyper-consumption and the notion of perpetual growth that is inherent to it. This is why certain scholars opt for the term Capitalocene over Anthropocene, i.e. a critical perspective that questions the way the dominant economic system structures our relationship with the planet.

Reflecting on the balance of life and minerals that has shaped the Earth’s story reveals dynamics that extend beyond traditional geological and biological confines, encompassing economy and society in the broader narrative of the Capitalocene: a way to confront the repercussions of mineral resource extraction and the implications of our role in shaping the planetary course. Recognising our collective trajectory’s entanglement with geological processes prompts a re-evaluation of our relationship with the Earth, demanding a recalibration of our existence with the dynamic forces of geology, acknowledging that the legacy we are forging hinges on a profound understanding of the interconnectedness of ecosystems—where the boundaries between the living and inert soften.

Rethinking Transition

Denise Medico (she, her) is a clinical psychologist and sexologist, and a professor in the Department of Sexology at UQAM. Her research focuses on subjectivity, corporeality, and gender, and on the development of inclusive and affirmative approaches to psychotherapy. She has founded Fondation Agnodice, which works to develop resources for young trans people and their families. She has also co-founded Centre 3, an inclusive feminist training and psychotherapy centre open to all. She is also part of the research group of least’s project Peau Pierre, for which we interviewed her.

Recently, the word ‘transition’ to describe the journey of transgender people has been questioned. Do you also think it is an ineffective term? And why?

Some twenty years ago, before the idea of ‘transition’, there was one of ‘transformation’, and before that, one of pathology: transgender people were considered to have mental issues of which they had to be cured. The ‘transition’ metaphor introduced the idea of a path between two genders, considered as two places. It is a ‘geographical’ metaphor that spoke to many people, including some trans people. These were mostly trans women who had started their transition process quite late in life and who had grown up with binary and even ‘naturalising’ references. In a nutshell, the idea of transition implies going from one gender to another. Thinking about it now, from a more queer, post-Butler* perspective, this is an idea that we are beginning to deconstruct. Genders are social places, grammars, and systems of thought. Gender incongruity is the idea that the ‘place’ you have been assigned is not relevant to your experience. However, if gender is non-binary, then the idea of transition changes too, because inherent in the idea of transition is that of a starting point and an end point. Some people experience it in this way, but the whole process is generally more fluid. A person who has begun this process, who is in the process of change can change direction at any time: the process matters, not the endgame. Moreover, on a political level, at a time when anti-trans movements are very strong, one attack that comes up often is based on the idea of ‘changing gender’. Hence, it is better to talk about ‘gender affirmation’ or ‘gender journey’, not least because we all affirm a gender, whether binary, non-binary, neutral, stable or fluid.

Why is it important to build a vocabulary that is inclusive of trans people? Can you give me an example of a word that would be good to have in everyone’s vocabulary?

While thinking is not based on vocabulary alone, the latter does play a fundamental role. To think of yourself, you need the words to do so. One word that has had a significant impact is ‘non-binary’. There have always been people who felt neither male nor female, that is nothing new, but until now they have never had the possibility to think of themselves in that way. Not being able to think of oneself is a painful experience that leads to depressive, negative feelings. When these people tell you how their life changed the moment they were able to think of themselves with a word, they speak of it as an epiphany: there is a before and an after. The word ‘non-binary’ is a good example, but it is a politically charged word, because it leads to rethinking the whole gender system and the ‘naturalness’ of the male-female hierarchy.

How important is the contribution of feminism in building a vocabulary and the sexual and mental health paths of trans people?

It is not only about transgender people: eliminating these stereotypes affects all people, and if you are ‘different’, it will affect you even more. Things would not be the same today without the history of feminism, without Simone de Beauvoir or Judith Butler. Certain realities already existed, but it was only after they had been conceptualised that they began to change society. Actually, I do not understand why TERFs (trans-exclusionary radical feminists) have a problem with trans people, because by starting from a progressive deconstruction, from the idea that sex is not gender, we produce a much more radical and effective critique of the system that oppresses women by structuring society in a hierarchical way.

Medical technologies are often seen as neutral, and so is science, when in fact they are processes that bring people’s private experience into the public sphere of scientific knowledge and political power and sometimes reinforce forms of oppression. How do medical technologies influence the construction of the trans body, also on the level of imagination? How can medical technologies and pathways be developed that are more effective for trans people?

It is a complex issue. Without medicalisation there would be no trans people, because it was medicine and biomedical research that conceptualised and studied hormones. At the end of the 19th century, the idea emerged that there might be something in the body that determines the male or female gender, leading to the concept of hormones. The history of the transgender movement is linked to endocrinology, but also to psychiatry – both of which were based on a binary vision and worked as ‘gatekeepers’. Today the medical perspective is less binary, but the issue remains complex: hormone therapy, for example, now offers three possibilities, either to obtain the characteristics of one gender, suppress the characteristics of the other, or block the hormones that develop these characteristics. The medicalisation of gender affirmation processes has been debated for twenty years and trans people do not all agree. For now, the position of maintaining medicalisation for economic reasons prevails: if you want to be reimbursed by insurance companies, you have to bow to the logic of health and a diagnosis. Moreover, far-right parties and certain anti-trans movements want to prevent medicalisation rather than control it. Not to mention the medical world, where training is not critical, theoretical, or epistemological, but essentially technical.

Addressing gender issues requires a cross-disciplinary approach. Which disciplines need to be brought together? And how is this interdisciplinarity managed?

Different disciplines of care are involved, although this varies from country to country: in Switzerland, for example, gender affirmation paths are usually followed by a psychotherapist – especially now that they are reimbursed by insurance companies – whose role is to support the person and sometimes report back to the endocrinologist or surgeon. Endocrinologists work with hormone therapy. One specialisation that has grown in importance in recent years is torsoplasty surgery, which, with or without hormone therapy, remains the most popular treatment. Contrary to popular belief, genital surgery is no longer the cornerstone of gender affirmation. Beyond medicine, critical sociology is an important discipline, because when working with trans people, it is important to question what one believes to be ‘natural’.

Aurore Favre, How to crochet a mask, 2023. ©Aurore Favre.

In your experience, is this a good practice? Or are there other specialists who should be involved, or who are involved but should have more space?

It depends: there are different paths that require different approaches. If you were assigned the female gender at birth and feel non-binary, you may want to live without hormone therapy or you may take hormones, often in micro doses, and consult an endocrinologist for advice. You may need surgery: if you cannot stand your breasts, you will need to wear a binder, but they are quite uncomfortable as they compress the ribcage and hinder your breathing, thereby increasing feelings of anxiety. If on the other hand you want to become a transgender man, you might take testosterone. This will change the tone of your voice and your ‘passing’ (i.e. when someone is perceived as a gender they identify as or are attempting to be seen as, rather than their sex assigned at birth) will be perfectly masculine. After just one year of hormone therapy, most transgender people already see noticeable changes. If, on the other hand, you were assigned male at birth and have already gone through puberty, all testosterone-induced changes will not be reversible: for instance, if your voice has already changed, you will not be able to regain a higher-pitched range, and you may feel a greater need for surgery. What’s more, at the moment, because of what is happening politically, people are acting more cautiously: one of the strategies of anti-trans movements is to scare clinicians, sometimes by direct threats, sometimes by filing lawsuits and denunciations with the authorities in order to saturate our time.

And how is this possible, with which motivations?

You can be reported for abusive practices, for example. Even if this turns out to be untrue, you will have put considerable energy into managing the situation. Transgender discourse is rarely visible, if not invisible in public discourse. The practice of ‘passing’ itself counteracts and invisibilises trans identity. That is true, but at the same time we should not think that the trans movement is only made up of politically minded people for whom being visible, asserting an identity, and criticising social structures is possible and desirable. Not all trans people are like that and those who aren’t are not visible, because they do not write or demonstrate. Also, they often have a strong, internalised sense of transphobia, so they try and remain as discreet as possible, because they live in fear. There is a very active non-binary trans movement, particularly in the art world, which is very sensitive to these issues, but which does not represent all trans realities.

I imagine that issues of class or origin, for example, have a part in this.

Education and class play a role. The trans political world is much more present in universities and the arts than in other contexts. It also depends on gender: many transgender people who come out later are people who were assigned male at birth, who suffered trauma as children, and who faced a difficult path before daring to assert themselves. They therefore have a visceral fear of violence from others because they know it well. Hence, they dream of perfect ‘passing’, which is even more difficult for them, because if they have tried to assert themselves later in life, they have already been masculinised by puberty, making ‘passing’ all the more difficult. There are also people with different personality structures, who function differently, cognitively speaking, or who are neurodivergent. Some people, who may be on the autism spectrum as we often hear, tend to think more rigidly, so being ‘normal’ is very important to them. Even if gender is not something that ‘speaks’ to them per se, they look at ‘how it is done’ in society and want to do the same thing.

How important is situated knowledge in the discourse of medical technology and pathway construction? How important is the osmosis of knowledge between trans people and the world of people caring for their sexual and mental health?

There are more and more trans people among us. We are not a cis group, but a very mixed group, and we have worked hard to enable transgender people to access university. When we work from a trans perspective, we have a policy of positive selection – the intentionality is important. As a society, the less we feel obliged to conform to norms, the less trans pathways will be obsessively determined by successful ‘passing’. Instead, we will have a society in which even a trans or non-binary body can exist without countless surgical operations. There are trans people, for example in the art world, who stage their actual bodies, just as there are trans people whose ‘passing’ is completely successful, but who continue to get surgery – perhaps because they are not satisfied with the body they have and are willing to undergo extreme and risky procedures for cosmetic purposes for example. That is also why it is important for some people to undergo psychotherapy, because they will never achieve this ideal – an ideal that does not exist.

Did you find different experiences depending on the contexts, the landscapes, the environments where people live? I was reading a book by Jules Gill-Peterson titled Histories of the Transgender Child and I was struck by the fact that in some rural settings in the US, even very small ones, at times when medicalisation was not an option, trans people managed to have a life that in some way represented their gender.

You cannot separate the idea of ‘passing’ from the idea of social violence; successful ‘passing’ means being invisible so as not to be in danger. The urban-rural opposition is true, but there are many exceptions: in some small communities, there are people who are referred to as that person, who can afford to assert their gender. We conducted a study in a rural area of Quebec on couples in which one person had gone through a gender affirmation process. Almost all the studies focus on couples who were assigned female at birth. These are almost the only studies we have in this sense. They are usually carried out in highly politicised contexts, in cities, with people who go to university and study gender studies. Immigration is also an important factor. For example, in Canada there is a phenomenon of LGBTQIAP+ immigration, but it is complicated: take, for example, a trans woman from the Turkish countryside, where gender perception is extremely binary and the importance of ‘passing’ is dictated by fear, who arrives in Montreal, a queer and non-binary city. Such a person will have the impression of being totally unsuited to Montreal society. You cannot talk about intersectionality without thinking about issues of race but also immigration, social origin, where you are going and where you have come from.

*Passing describes the experience of a transgender person being seen by others as the gender they want to be seen as.

*Judith Butler is a philosopher and gender studies scholar whose work has influenced political philosophy, ethics, and the fields of third-wave feminism, queer theory, and literary theory. Butler is best known for their books Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990) and Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex *(1993), in which they challenge conventional, heteronormative notions of gender and develop the theory of gender performativity.

The Gesamthof recipe: A Lesbian Garden

Hedera is a collective observation of the overlap between postnatural and transfeminist studies.

Each volume gathers insights related to these topics in the form of conversations, essays, fiction, poetry, and artist content. Hedera is a yearly publication, and its first volume features “The Gesamthof Recipe: A Lesbian Garden” written by artist Eline De Clercq.

The Gesamthof is a non-human-centred garden, it is a garden without the idea of an end result and it is about working towards a healthy ecology. This recipe shares how we garden in the Gesamthof.

Rest, observe.

Start with ‘not a thing’, it is the quietude before one begins. Rest as in ’not to take action yet’. I find this a good begin, it has helped me many times. When I plan to work in the garden I put on my old shoes, take a basket with garden tools and the seeds to sow, and I open the gate and step into the garden and - stop. Not to act at once, but to wait a moment before beginning gives me time to align myself with the soil, the plants, the temperature, the scents, images and sounds. I look at the birds, the snail, the beetle on a leaf. I walk along the path and greet the plants and stones. Like me, in need of a moment, they too need to see who entered the garden. I know the plants can see me because they can see different kinds of light and they grow towards light and they see cold light when I stand in front of them casting my shadow on them. They can see when the sunlight returns and I moved on. This is the first connection with the garden: to think like a gardener-that-goes-visiting. Donna Haraway writes about Vinciane Despret who refers to Hannah Arendt’s Lectures on Kant’s Political Philosophy; ‘She trains her whole being, not just her imagination, in Arendt’s words “to go visiting.”’ all from the book Staying With The Trouble (see the reading list below). Sometimes it is all I do, and time passes, for an hour and more I feel truly alive with listening, feeling, scenting and seeing. I can taste the season.

Your senses & your mind.

To feel as well as to think along with nature. This is perhaps the hardest to explain, but this is the way I learned to garden from when I was helping as a volunteer in the botanical garden in Ghent. While there is a lot to learn and to remember: you can look it up most of the time. There are plenty of books on what kind of plant likes to live in what kind of conditions. Those facts are easy to find. For me, the rational explanation comes in the end, like a litmus test to see if a theory works. I like to begin with experiencing things: feeling the texture of a leaf, noticing the change in temperature when it’s going to rain, comparing soil by rubbing it between your fingers, smelling soil, plants, fungi and so on. Senses connect us to all kinds of matter in a garden and they help one to become part of the garden. Donna Haraway writes about naturecultures, an interesting concept to rethink how we are part of nature and how the dichotomy of nature and culture isn’t a real contradiction. It is an argument to stop thinking as ‘only human’ and start becoming a layered living togetherness. It’s in our best interest to feel nature again with our senses. At the same time, be aware that many plants are poisonous and/or painful, they might hurt you so don’t trust your instincts too much without consulting facts.

Gesamthof, a non-human-centred garden.

The patch of soil I consider as the shared garden, the Gesamthof, is part of a planet full of bacteria, protista, fungi, plants and animals and all of these enjoy being in the garden too. I try to give the fungi some dead wood to eat, and I don’t use herbicides and pesticides while caring for the plants. This is kind of obvious, it’s basic eco gardening, but it also concerns the benefit of the entire garden. The important question is: who is getting better from this? When I count in birds, insects, plants and fungi and the needs they have to survive in a city, then a small garden is for the benefit of all of these and the ruined artichoke isn’t much of a disaster, many big and small gardeners enjoyed being with the artichoke, drinking the nectar, eating the leaves, weaving a web between the dried stalks. Thinking of all us gardening together changes the purpose of the garden, it’s no longer focused on humans only. Often I see a seedmix for bees in the garden centre, but every garden has a different relation to bees, sometimes with solitary wild bees living of a single plant species not having any interest in a human selected seed mix with a colourful flowers display. The question “Who is getting better from this?” stops me buying things for my pleasure and teaches me to be happy when a healthy ecology is establishing.

Thinking like this has made me question the situation of indoor plants. If they could chose between living inside a house in a cold country or being outside in a warm location, wouldn’t they prefer to sense the sunset and feel the wind in their leaves? Am I keeping plants in the house for my own benefit? Would plants grow in my house if I didn’t water them and look after their soil? Should I put plants in places where they naturally wouldn’t grow? I have decided not to buy new plants for in the house, I will care for the ones I am living with as good as I can. Does the garden end at the door? Or do I live in the garden too?

The diversity of city life in a garden.

The opposite of local wild nature is not a foreign plant, but a cultivated plant. The garden combines native plants from many continents, I grow African lilies next to stinzen flowers and local wild plants; they get along well. I’m not a puritan who wants to grow only one colour of flowers or only authentic plants, I see the garden more like a city where we arrive from all corners of the world. Plants don’t know borders, they don’t care for nations, if they like the place they’ll grow happily. But humans don’t always know what they are planting and we build so much & take away so many plants and replace the green in our gardens with other varieties, often cultivars that don’t interact with local species. A cultivar is the opposite of a wild plant, a cultivar is selected for a quality liked by humans but not always in regards to the ecology with other species. Some cultivars are great plants, they are strong and beautiful and interact in symbiosis with the rest of nature. But some cultivars blossom at the wrong time to attract insects, or they don’t provide anything for the others to interact with. In other words, they are planted to be pretty and not to take part of a wholesome nature. Because of these cultivars we are rapidly losing authentic genomes of plants that are important to preserve nature. When you have a garden that is designed and planted with only these kind of cultivars you don’t invite nature in. You might just as well have plastic flowers. The opposite is to care very much for the diversity of ‘pocket’ nature, what was growing in this pocket of the world, and to try to find old species specific for this area that have been around for thousands of years, and have become an important sustainable link within the local ecology of insects, plants, fungi and other living beings. I let the weeds grow in the garden to support the network of insects needing those plants, and birds needing the insects, and local plants needing these insects and birds as well and so on and so on. The gardens in a city are like corridors, they connect insects, plants and fungi into a greater network that is necessary to sustain these species. While we see walls and hedges around a garden, and we might think of it as our island, it is part of a larger green archipelago where plants, birds, insects and others are not hindered by walls. Every city has only one garden made up of all these green islands just a few streets apart.

We shouldn’t break this chain of connected nature by losing our interest in local wild plants, often seen as uninvited weeds and taken for granted, they are very important in a diversity that expands with every living species. Since we’re living in a time of mass extinction & losing multiple species every day, all the things we can do count and in a garden we can let nature in. Sometimes I buy organic local plants from small nurseries to support their effort for conservation. But there is very little money involved in the Gesamthof. When I started to work in the garden I got many plants, seeds and cuttings for free and in return I also like to give away sister-plants so the Gesamthof lives on in other gardens. This is how plants from all over the world became part of the Gesamthof, and they all are very important in the diversity of the garden. There are Spanish bluebells and a Chinese Wisteria that were planted by the monks from the monastery a long time ago, they survived decades of neglect, there are Evening Primroses that most probably arrived on the wind from neighbouring plots and there are colourful tulips, both wild and cultivated that attract all kinds of human and non-human visitors.

The garden will help you.

This is the strangest thing, but since I’m working in the Gesamthof, plants have arrived from all kinds of places, they have often been given to me for free. Also garden materials, pots & books seem to come without much effort. They arrive from lots of generosity from others. I work in the garden, but not to create ‘my garden’, I see the garden as its own entity and I’m ‘the one with arms and legs’ who can help where needed. Many other living things help as well. Wasps have been eating the aphids, Cat’s Foot (Glechoma hederacea) is keeping my path free from weeds and the Titmice eat the spiders that make a web on the garden path (thank you, I don’t like walking into spider webs). I’m one of the garden critters (a word I borrow from Donna Haraway, critter isn’t as attached to creation as creature is) and I love seeing the other critters thrive at their work. I’m not doing this alone. While I do put in a lot of work, I see it as a part of my artistic practice. Gardens are often not seen as an artwork, but to do research, to add a different perspective, to engage with the soil, water and living beings, to build a different kind of place and share this as a public work is very much how I see art work. Art can be more than making and showing things, it can be interaction, awareness and sharing too. The Gesamthof works without a financial set up, it is thriving by generous neighbours who share their plants, seeds, helping hands and advice. This garden is giving more than it costs.

Don’t make a garden design.

This might sound counter intuitive, but being in the garden very often, one should know what the garden needs and that should be enough of planning. The usual garden plan is often seen as to give shape to the idea of an ideal garden, with a sketch of what to plant where, what colours to combine, where the path should be and in what material and so on. It would mean to put oneself above all else as the creator, and it means setting oneself a goal to work towards, with in the end a ‘beautiful garden’. I don’t think gardens should be ‘made’ beautiful, just like women shouldn’t be judged on a scale of beauty. It’s a binary opposition, a way of thinking that leads to a lot of suffering both in and outside of the garden. Instead let the garden take the lead and follow in its steps. You find a plant that likes a sunny area, put it in the sunny part of the garden and it will thrive. Do you have a lot of bare soil in the shady area and you don’t know what to do with it? Look up shady plants, find a nice variety and let it grow in your garden. Do you need a path between the plants? Add the material that works best in that place (for instance a forest kind of material would be tree bark, and recycled materials also make excellent paths). This way you’re growing a cultivated wild garden that will be beautiful all by itself just like nature is. Use creativity in how you arrange stones along a path, in how you support plants that will fall over, in how to add water and feeding stations, in creating fine labels, in making drawings that will later on help you to remember what you planted where… there is lots of room for creativity.

Intersectionality & botany.

The connection between botanical classification systems and people classification systems illustrates how the same mode of thinking is applied to both our gardens and us as people. Botany is full of anthropocentrism and it is not bad to be aware of this, the lesbian garden reframes this use of gardens. Suddenly the invisible norm of who usually benefits from gardens is no longer in place. ‘Lesbian’ means nothing if it is not connected to racialized people, to class differences, to living with disabilities, to age and all the other aspects gathered in Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectional theory. To put intersectionalism into practice means asking the ‘other question’: who benefits from this garden?

- Bees opens up the discussion on native plants, their genomes and diversity in gardening.

- Plants opens up the discussion of the colonial past, systems of economics, and who has a ‘right’ to extract.

- An audience that visits art spaces (the Gesamthof is accessible trough the Kunsthal Extra City) opens up the question of class, inviting the ‘other’ in, LGBTQIAP+ friendly spaces etc.

- Me opens up the question of access & responsibility that comes with privilege.

To ask the other question means that we are aware of others. Is the Gesamthof appropriate for children? Should it be? Should we take out all the poisonous plants, the pond, the bees hotel etc if we want children to be safe? There is a fence around the Gesamthof to keep wandering people out, because the garden is certainly not safe for everyone and not everyone is safe for the garden.

Atemporal gardening.

Every place carries a past into its future. The past is not a distant island, it’s very much with us in this thick present (again Donna Haraway’s words, the thick present is like a composted layered presence). In my garden I don’t want to be blind for what is present from the colonial past. It takes effort to find out how all of this is linked, how the history of botanical gardens is woven into to the need for classifying. It is hard work to learn about colonialism and gardening because it’s not as clearly visible as for instance plantations and slavery are linked to cotton and coffee. A garden is often more like a collection of plants bedded into a designed space and the colonial past is not a comfortable topic in garden programs. It takes visiting the past to find out what is here today. For me it meant going to the botanical garden in Meise and looking at the plants brought back from colonies. It also meant digging in the past of the Gesamthof’s location in the monastery, who was gardening here before me? How can I work with ecology towards a better understanding?

Note: People suffer from plant-blindness (J. H. Wandersee and E. E. Schussler, publication ‘Preventing Plant Blindness’ from 1999), it means we don’t see the plants that we don’t know and by giving garden tours one can share the awareness of this cognitive bias. In a lesbian garden the cognitive bias rings a bell, without representation people have a hard time discovering what is different about them. Many lesbians don’t know that they are a lesbian when they grow up, and they see themselves through the norm of a heterosexual society while a part of who they are remains empty for themselves. Like plant-blindness, this abstraction of a norm can be countered by looking at the differences as positive characteristics.

Ongoing change.

A garden is a nice form of art & activism, it is a healthy activity that helps to relieve stress and anxiety. It is working towards change by educating one’s self and each other, it is becoming aware of nature and changing our way of thinking. It is pleasant: the scent, the view, the touch, the sound, it’s a nice place to be. I become very aware of the moment when I sit in the Gesamthof. Time passes differently for all the inhabitants and visitors, and some of us spend a lifetime in this garden (most of the pigeons do) while for me it is very temporary. I will miss the Gesamthof when the new owners arrive in the monastery. But it doesn’t make it less worth it, on a larger scale gardening means ongoing change, and we can enjoy every moment of it. Never is a garden a fixed thing, it is never finished and there is no ‘end’, it just moves into different places.

Stills from Gesamthof: A Lesbian Garden, Annie Reijniers and Eline De Clercq, 2022.

Peau Pierre: an audio capsule

TRAVELING BODY by Jonas Van

In a room in the heart of Geneva, in the middle of the afternoon, our group of artists is meeting. Large quantities of water flood the ground. Collectively, we try to move the water with our bodies. But it flows at a speed we don’t understand; we can’t physically transport it.

The human body has around 100,000 kilometres of blood vessels, enough to circle the Earth two and a half times. Blood vessels are made up of arteries and veins. “Vein” comes from the Latin “vena”: a small natural underground water channel. In fact, by holding the water in our hands, we are imitating the body’s own blood circulation, but outside it.

The water on the ground catalyses our memories. And when our skins finally touch, water is the intermediary in this encounter. This is how a crack in time opens up in this room in the heart of Geneva. Our skins, imitating the movement of the circulatory system, have gradually warmed up to produce enough friction for the water to take the body on a journey through space-time. The next exercise was to talk about where we had travelled. These journeys took the form of audio capsules.

This speculative story is part of the T-T Transition Glossary, a tool designed by Ritó Natálio to develop a form of environmental education that encourages artistic practices as a means of understanding and applying ecological theory to societal challenges. This audio capsule is a work by Jonas Van Holanda, inspired by the Peau Pierre project, workshops, for which he was artist-in-residence.

Peau Pierre: an Audio Capsule by Jonas Van Holanda

Spillovers

Spillovers by Rita Natálio intertwines performance and writing, imagination and somatic experience using transfeminism and ecology as their tools. It is an unusual text, a sex manual, a sci-fi essay on water and pleasure that offers a reinterpretation of Lesbian Peoples: Material For A Dictionary (1976) by Monique Wittig and Sande Zeig.

Spillovers, an excerpt of which follows, represents a glossary defining sensorial and choreography protocols as tools for deciphering and understanding human/non human grafts. Movement is the matter that forms her writing and gathers archives of images and books about ecofeminist theories and practices.

In 2020, a book was found in a well. This well, as many other of life’s cavities, was contaminated by superficial practices of intensive monoculture. Its water, having turned unsanitary, had then dried up for quite a long time. It was inside this hole, then, dried up yet viscerally imprinted by the memory of water, that a translation of Lesbian Peoples: Material for a Dictionary, written in 1976 by Monique Wittig and Sande Zeig, was found. Back then, this book could have been read as a manual or a foundational text for a certain kind of religious cult or spiritual ritual. Much later we learned that it was a diary where the fleeting transformations of transcorporeal and elemental language were recorded, as well as an archive of practices which assembled and connected descriptions of objects, figures, problems and politico-affective strategies that the community of Spillovers (at that time simply called “lovers”, or “lesbian women”, plain and simple) had tried to implement in their lives in the face of the growing aggressions from turbo-capital and the modern science of separations. See, for example, the dictionary entry for Circulation, on page 31 of the English translation:

Circulation

Physical process of intermingling two bodies. Given two bodies full of heat and electricity released from the skin through every pore, if these two bodies embrace, vibrate and begin to mix, there is a circulation and conduction reaction which causes each pore to reabsorb the energy that it had previously emitted in another form. This phenomenon, by the rapid transformation of heat and electricity into energy, produces an intense irradiation from those bodies which are practicing circulation. It is what the companion lovers mean when they say, “I circulate you,” or “you circulate me.”

In the book, one came to understand that lovers perceived themselves as membranes of sorts, seeking to relate to one another through their own ecology of connections and its limits. Yet, in 1976 many of us were only 2 years old or had just learned how to use a ring or a Y-shaped stick to locate water. And the problem was that we did not know whom we meant when we said “we”, as one of us said at the time(1). The plural personal pronoun was a practice that merely allowed us not to disappear into other pronouns that overlooked our lives, even though we did not know exactly who we were.

“Lesbians” or “women” were container-words that seemed inadequate, ill-suited. In 1976, we also knew very little about water-witching, hydrofeminism or the flow of water through different scales, bodies and genders. To balance ourselves on 2 legs was something we could do without a hitch, as was reading, though certain constraints of vision and verticality prevented us from touching the irradiation of energy in more complex ways. The search for water with a stick demanded an initiation, a special care, and the use of the antennae shared by the webs of lovers was a technology not (yet) easy to access.

The glossary presented here proposes a continuity with Wittig and Zeig’s clairvoyance, by elaborating further on the rings and fiction bags(2) that Spillovers must touch and weave in order to tangle the times and produce water. No need to fear getting wet. And much less feeling pain when drinking dirty water, or watching a water-tap blazing with methane gas released from fracking. All these dimensions, painful though they are, organise love among Spillovers. And although at times one can dispense with the centrality of the eyes and reading, images and conversations with indigenous film practices, radical poetry and counter-colonial philosophies are invoked here. They call for simple enough things: that, in the beginning, worlds were created and lived through these references, from Dionne Brand to the Karrabing Film Collective, from Astrida Neimanis to Ursula K. Le Guin. This is the necessary and anti-heroic gesture of 2020: to forget and to cut off all communication with the anthropocenic elites, all the while carrying water for those in need. As a Zen proverb says: “Before enlightenment (…) carry water. After enlightenment (…) carry water.”

GLOSSARY

1. Spillovers

To be a lover means, always, to be a Spillover. The “spill-over effect”, which leads to the spillage of liquids and intentions, is the primary condition for the multi-species and intersex amorous cooperation, whether these liquids are genital, lacrimal or jet-pumped from less obvious parts of the body, such as the elbows or feet. Water is produced at the encounter of 2 or more entities and, if properly placed in bags, it can mutate into the condition of amniotic fluid, which has strong amnesic properties, and can gestate other entities. It is not common for amniotic fluid to be ingested, except when a Spillover is buried under dry soil, a practice that aims to generate water in periods of severe shortage or contamination. Spillovers are all those who, in a life without protagonists, wish to overflow, to spill over and out of themselves, and thus cross the soft borders between peoples, territories and landscapes.

2. Bags

Bags are Spillover technologies with a multitude of functions. Bags can generate and carry babies and can be swapped from body to body regardless of gender. Bags can carry water. Bags can carry amniotic fluid and they can also carry ideas or stories. They are self-healing and biodegradable and yet there is a limit to their use, they are not disposable. Bags do not simply generate human babies, they may also create vegetable or mineral kinship and that’s why one sometimes says that a baby plant or a baby rock was born. Bags also serve as a strategy of resistance in the case of severe groundwater contamination (as shown in the film “Mermaids or Aiden in the Wonderland”, by the Karrabing Film Collective from 2018). In emergency situations, they can break through hard borders such as those that divide today’s nation states. They are tools for the migration or transmigration of bodies which have the temporary ability to deactivate passports.

3. Iris

It is said that a long time ago Spillovers experimented with carrying water, and then experimented with words, in the above-mentioned bags, thus supplying multi-species societies with unexpected and opaque bonds. Since then, whenever the water touches a word inside the bags the latter may split it into pieces: this happened, for example, with the words clitoris (clito-iris) and iridescent (iris-descent), instruments of emotional concentration and unfolding. Since then, when 1 or more Spillovers manage to carry a bag full of water into a territory ruled by monoculture, the Spillover’s iris swells up like a clitoris, thus generating a highly-hydrating golden shower followed by a multicoloured rainbow (an iridescent rainbow) in the sky. This event provides an intense pleasure, but one cannot call it heroic, or confuse it with the male tendency to worship singular phallic figures. In fact, as Spillover K. Le Guin puts it, “…it’s clear that the Hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage, a pedestal or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.”(3)

(1) Adrienne Rich, “Notes towards a politics of location”, 1984.

(2-3) Ursula K. Le Guin, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”, 1986.

Bodies of Water

The transition of life from water to land is one of the most significant evolutionary milestones in the history of life on Earth. This transition occurred over millions of years as early aquatic organisms adapted to the challenges and opportunities presented by the terrestrial environment. One of those was the need to conserve water: living beings, in a way, had “to take the sea within them”, and yet, although our bodies are composed mostly of it, biological water actually counts for just 0.0001% of Earth’s total water.

Water is involved in many of the body’s essential functions, including digestion, circulation and temperature regulation. Nevertheless, our bodily fluids, from sweat to pee, saliva and tears, are not just contained within our individual bodies but are part of a more extensive system that includes all life on Earth, blurring the boundaries between our bodies and more-than-human organisms, connecting us to the world around us. Scholars described this idea as hypersea: the fluids that flow through our bodies are connected to the oceans, rivers and other bodies of water that make up the planet and are part of a larger system that connects all living beings together.

Recognising the interconnectedness of all life on Earth and the role that water plays in this interconnected web can help us better understand our place in the world and the importance of working together to protect and preserve this precious element. However, to fully grasp the consequences of this perspective, it is necessary to consider some significant issues addressed by scholar Astrida Neimanis, the theorist of hydrofeminism, in her book Bodies of Water.

One of the main contributions of hydrofeminism to the discussion on bodies of water is the proposal to reject the abstract idea of water to which we are accustomed. Water is usually described as an odourless, tasteless and colourless liquid and is told through a schematic and de-territorialised cycle that does not effectively represent the ever-changing, yet situated, reality of water bodies. Water is mainly interpreted as a neutral resource to be managed and consumed, even though it is a complex and powerful element that affects our identities, communities and relationships. Deep inequalities exist in our current water systems, shaped by social, economic and political structures.

Neimanis shares an example explicitly related to bodily fluids. The Mothers’ Milk project, led by Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook, found that women living on the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation had a 200% greater concentration of PCBs in their breast milk due to the dumping of General Motors’ sludge in nearby pits. Pollutants such as POPs hitch a ride on atmospheric currents and settle in the Arctic, where they concentrate in the food chain and are consumed by Arctic communities. As a result, the breast milk of Inuit women contains two to ten times the amount of organochlorine concentrations compared to samples from women in southern regions. This “body burden” has health risks and affects these lactating bodies’ psychological and spiritual well-being. The dumping of PCBs was a human decision, but the permeability of the ground, the river’s path and the fish’s appetite are caught in these currents, making it a multispecies issue.

Hence, even though we are all in the same storm, we are not all in the same boat. The experience of water is shaped by cultural and social factors, such as gender, race and class, which can affect access to safe water and the ability to participate in water management. The story of Inuit women makes it clear how water, even if it is part of a single planetary cycle, is always embodied, and so are bodies of water with their complex interdependence. While hydrofeminism invites us to reject an individualistic and static perspective, it also reminds us that differences should be recognised and respected. Indeed, it is only in this way that thought can be transformed into action towards more equitable and sustainable relationships with all entities.

Neimanis also approaches the role of water as a gestational element, a metaphor for this life-giving substance’s transformative yet mysterious power. Like the amniotic fluid that surrounds and nurtures a growing animal, water can support and sustain life, nourish and protect, and foster growth and development. In this sense, water can be seen as a symbol of hope and possibility, a source of renewal and regeneration that can help us navigate life’s challenges and transitions. Like a gestational element, water has the power to cleanse, heal and transform. While seeking to find our way in a constantly changing world, we can look to water as an inner source of strength and inspiration, a reminder of life’s resistance and adaptability and the potential that lies within us all.

Image: Edward Burtynsky, Cerro Prieto Geothermal Power Station, Baja, Mexico, 2012. Photo © Edward Burtynsky.

Intimity Among Strangers

Covering nearly 10% of the Earth’s surface and weighing 130.000.000.000.000 tons—more than the entire ocean biomass—they revolutionised how we understand life and evolution. Few would probably bet on this unique yet discrete species: lichens.

Four hundred and ten million years ago, lichens were already there and seem to have contributed, through their erosive capacity, to the formation of the Earth’s soil. The earliest traces of lichens were found in the Rhynie fossil deposit in Scotland, dating back to the Lower Devonian period—that of the earliest stage of landmass colonisation by living beings. Their resilience has been tested in various experiments: they can survive space travel without harm; withstand a dose of radiation twelve thousand times greater than what would be lethal to a human being; survive immersion in liquid nitrogen at -195°C; and live in extremely hot or cold desert areas. Lichens are so resistant they can even live for millennia: an Arctic specimen of “map lichen” has been dated 8,600 years, the world’s oldest discovered living organism.

Lichens have long been considered plants, and even today many interpret them as a sort of moss, but thanks to the technical evolution of microscopes in the 19th century, a new discovery emerged. Lichen was not a single organism, but instead consisted of a system composed of two different living things, a fungus and an alga, united to the point of remaining essentially indistinguishable. Few know that the now familiar word symbiosis was coined precisely to refer to this strange structure of lichen. Today we understand that lichens are not simply formed by a fungus and an alga. There is, in fact, an internal variability of beings involved in the symbiotic mechanism, frequently including other fungi, bacteria and yeasts. We are not dealing with a single living organism but an entire biome.

Symbiosis’ theory was long opposed, as it undermined the taxonomic structure of the entire kingdom of the living as Charles Darwin had described it in On the Origin of Species: a “tree-like” system consisting of progressive branches. The idea that two “branches” (and, moreover, belonging to different kingdoms) could intersect called everything into question. Significantly, the fact that symbiosis functioned as a mutually beneficial cooperation overturned the idea of the evolutionary process as based on competition and conflict.

Symbiosis is far from being a minority condition on our planet: 90% of plants, for example, are characterised by mycorrhiza, a particular type of symbiotic association between a fungus and the roots of a plant. Of these, 80% would not survive if deprived of the association with the fungus. Many mammalian species, including humans, live in symbiosis with their microbiome: a collection of microorganisms that live in the digestive tract and enable the assimilation of nutrients. This is a very ancient and specific symbiotic relationship: in humans, the genetic difference in the microbiome between one person and another is greater even than their cellular genetic difference. Yet the evolutionary success of symbiotic relationships is not limited to these incredible data: it is the basis for the emergence of life as we know it, in a process described by biologist Lynn Margulis as symbiogenesis.

Symbiogenesis posits that the first cells on Earth resulted from symbiotic relationships between bacteria, which developed into the organelles responsible for cellular functioning. Specifically, chloroplasts—the organelles capable of performing photosynthesis—originated from cyanobacteria, while mitochondria—the organelles responsible for cellular metabolism—originated from bacteria capable of metabolising oxygen. Life, it seems, evolved from a series of symbiotic encounters, and despite numerous catastrophic changes in the planet’s geology, atmosphere and ecosystems across deep time, has been flowing uninterruptedly for almost four billion years.

Several scientists tend to interpret symbiosis in lichens as a form of parasitism on the part of the fungus because it would gain more from the relationship than the other participants. To which naturalist David George Haskell, in his book The Forest Unseen, replies, “Like a farmer tending her apple trees and her field of corn, a lichen is a melding of lives. Once individuality dissolves, the scorecard of victors and victims makes little sense. Is corn oppressed? Does the farmer’s dependence on corn make her a victim? These questions are premised on a separation that does not exist.” Multi-species cooperation is the basis of life on our planet. From lichens to single-celled organisms to our daily lives, biology tells of a living world for which solitude is not a viable option. Lynn Margulis described symbiosis as a form of “intimacy among strangers”: what lies at the core of life, evolution and adaptation.

Learning from mould

Reading

Common Dreams

Peau Pierre

CROSS FRUIT

Faire commun

Arpentage

d’un champ à l’autre / von Feld zu Feld

Learning from mould

Physarum polycephalum is a bizarre organism of the slime mould type. It consists of a membrane within which several nuclei float, which is why it is considered an “acellular” being—neither monocellular nor multicellular. Despite its simple structure, it has some outstanding features: Physarum polycephalum can solve complex problems and move through space by expanding into “tentacles,” making it an exciting subject for scientific experiments.

The travelling salesman problem is the best known: it’s a computational problem that aims to optimise travel in a web of possible paths. Using a map, scientists at Hokkaido University placed a flake of oat, on which Physarum feeds, on the main junctions of Tokyo’s public transportation system. Left free to move around the map, Physarum expanded its tentacles, which, to the general amazement, quickly reproduced the actual public transport routes. The mechanism is very efficient: the tentacles stretch out in search of food; if they do not find any, they secrete a substance that will signal not to pursue that same route.

We are used to thinking of intelligence as embodied, centralised, and representation-based: Physarum teaches us that this is not always the case and that even the simplest organism can suggest new ways of thinking, acting and collaborating.

GLOSSARY OF TRANSITION (T — T) by Ritó Natálio

Context

People in transition are the sensors of an earth in transition.

Trans people are the radars of Earth’s transition.

Might water be a conductor of contamination?

RADARS OF TRANSITION

They say that “transition is work” and that it should be paid. Reading these words by Harry Josephine Giles (Wages for Transition, 2019), the Immigrant Writer from Southern Europe hopes to make sense of the veiled connection between human bodies thirsting for transformation (and involved in intimate processes of transitioning their assigned gender at birth) and the wider processes of apocalyptic transition of the Earth System (also known as the Anthropocene, or simply “climate collapse”). If transition is work, who would be the bio-proletariat common to these processes? The synthetic hormones administered in hormone therapies, or the hormones released into water sources from the mass use of the morning-after pill? Human bodies or non-human bodies occupied by transitions of all kinds?